Argentina’s New President Swaps the Chain Saw for the Blender

As Javier Milei’s new free-market economic measures start to roll out, devaluation has already started to impact everyone in Argentina—especially the middle classes and the poor.

Buenos Aires—After my plane landed here earlier this month, Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s former right-wing president, arrived at the same airport, to the same terminal. I don’t have much in common with him, but that day we both shared a similar itch: to head out and take the pulse of the streets hours before Javier Milei, the new chief executive, took office.

Bolsonaro went for a long stroll along San Martín, a commercial pedestrian walkway that cuts downtown north to south. Late spring in Buenos Aires is lush. The trees are in bloom, the sky is cellophane blue, and everything smells like jasmine. At the end of his walk, Bolsonaro stopped by the Hotel Libertador to meet Milei, who had been bunkered there since his landslide run-off victory on October 22.

“The world is very divided between left and right,” Bolsonaro told a radio host after a dap handshake with the Argentine self-styled anarcho-capitalist, both grinning for the photo-op, Bolsonaro in a white short-sleeved shirt, Milei in his leather jacket. “The left and the right are not opponents. They are enemies.”

Bolsonaro cawed in my headphones as I headed for a welcome asado with my family. I am the only one of us who emigrated, and every time I come back, I’m welcomed with the traditional Argentine-style barbecue. My four siblings and my parents still live in the middle-class neighborhoods where they grew up, in the center and west of Buenos Aires. Since before the election there has been an intensifying unease in our exchanges, and I felt those rifts getting worse in recent weeks. Much of this tension echoes Bolsonaro’s words: The split between left and right in South America has gone into overdrive. But now, the consequences of Milei’s free-market policies are almost palpable. The new president is a free-market libertarian, devotee of Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and the Chicago School of Economics. And he is starting to implement in Argentina a cocktail mix of orthodox liberalism that will make years of IMF intervention, Reaganomics, and the Washington Consensus feel like child’s play.

“His general guiding principles are tied to the Austrian school,” economist Maximiliano Castillo Carrillo told me. This means that his first measures are geared toward reducing public spending, curbing the money-printing machine, and ending price controls, which have kept food affordable to Argentine consumers. “Reducing state intervention, opening the economy, and strengthening the markets are in line with Milei’s ideas.”

None of this is new to the Argentine voter. During his campaign, Milei paraded these ideas on TV shows, promising to eliminate the Central Bank, dollarize the economy, dismantle ministries and secretaries, eliminate public education and public health services, reduce pensions and salaries for government employees, curb inflation, and reduce the fiscal deficit. He placed the ministerial system on the chopping block as soon as he took office on Sunday, consolidating 18 ministries into nine. And on Tuesday, his economy minister, Luis “Toto” Caputo –who was Central Bank president under the right-wing government of Mauricio Macri– announced the first round of measures in an 18-minute YouTube video. The “economic emergency” package includes a 54 percent devaluation of the peso, substantial cuts to energy subsidies nationwide, a reduction of government subsidies to transportation within the Buenos Aires metro area, and the nonrenewal of government employees’ contracts with less than one year of seniority.

Another former Central Bank director, Carlos Melconián, analyzed the first economic measures and joked about Milei’s adjustment package: “The chainsaw has been swapped for a blender,” he said, explaining that the targeted approach to budgetary cuts—the “chain saw”—had given way in the new measures to a broad-spectrum devaluation—the blender—that will impact everyone alike, more notably those living closer to subsistence level. Lately, the government also announced the nationalization of over $40 billion in private corporate debt, which economist Alejandro Bercovich called an international scandal. But one of the most frightening measures was announced on December 14: an anti-protest protocol aimed at enhancing the government’s policing powers, by allowing security forces to clamp down on roadblocks and marches. The protocol bolsters the government’s surveillance rights and allows the Security Ministry to penalize pickets and roadblocks by charging their organizers for expenses incurred by the police when intervening.

Like many Argentine families, mine has a direct connection to the public sector. Several of us are, or have been, academics at the Universidad de Buenos Aires, one of the highest-ranked public universities in the world, where Argentines enjoyed the right to study for free. Others do scientific research at public institutions such as CONICET, the national commission for scientific and technological research (an Argentine equivalent to NASA), or Presidencia de la Nación, one of the main coordinating ministries in the Argentine government. Basic research and development in the private sector in Argentina is negligible. That side of our dining table is already bracing for cuts and layoffs. But those who have mainly worked for the private sector, on the opposite side of the table, seem cheerful, even happy with Milei’s chain saw approach to public spending. Their openness to the new government, however, doesn’t mean that they expect to be spared by the looming economic carnage.

“Do you know what it is to live with this level of inflation for years?” one of my two brothers replied when I prodded him about his vote. He works as a marketing executive for a national fast-food company that may lose market share if the new government decides to fully open imports. “I know it is a risk, but we can’t go on like this forever. Something has to change.” After a pause, my other brother snapped: “Wait until you, and us, and all the corporations, start enjoying the Hobbesian freedom that Milei is promising, and brace yourself for the change.”

It is not surprising that this gap is, in part, generational. “Younger people, who went through their teenage years in the last decade, carry frustrations and they couldn’t find in the previous governments an answer or a voice that spoke to them,” Julieta Waisgold, a political consultant told me. “Milei keeps gaining popularity in social media, not just because of his savvy use of the platforms but mainly because of his message.”

The Argentine economy has collapsed, with draining reserves in the Central Bank and a foreign debt equivalent to 90 percent of the GDP, which ballooned partly because of some reckless borrowing by the right-wing government of Mauricio Macri, as well as a bad debt swap by the center-left government of Alberto Fernández. Today, people in this country are suffering the uncertainty caused by a year-over-year inflation rate of nearly 150 percent.

A few years back, it would have been hard for me to explain to my American friends what inflation feels like in your daily life. Not anymore. Imagine paying $1 for a gallon of milk in 2021, $2.5 the next year, and $6.5 in 2023. All while earning the same money you made in 2021. That is high inflation, Argentine-style.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Hyperinflation, however, is a totally different ballgame. I experienced it twice in my lifetime in Argentina and those memories are seared in all Argentines’ minds. When I was in junior high, in 1985, my parents would give me a small daily allowance to buy lunch at school. Every morning I had to run to the vendors during the first recess to buy whatever I could afford—a sandwich, a cookie, or a candy bar—because by the second recess, a couple of hours later, prices would have risen so much that the cash I carried became worthless. Every month, my parents themselves had to rush to the supermarket, paycheck in hand, to buy anything they could afford before their salaries’ value vanished. It felt as if the bills were made of hot sand, and the minute you touched them, they’d start running through your fingers.

“It is illogical to expect that 18-year-old kids who lived for the past eight years with high inflation, without any hope for the future, without experiencing any substantial social or economic advancements for them or their families, would want to support the Peronist movement or any political project that does not seem to understand them,” Victoria Liascovich, a young Peronist activist and former president of the Student Center at the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, told me. Victoria has formed her own political group, Falta Envido, and became an immediate sensation after the pro-Milei supporter she was debating in a radio show stood up and walked out on the live broadcast, overwhelmed and confused.

On inauguration day, December 10, Buenos Aires was hot and sunny. The jacarandas in Avenida de Mayo were in bloom with purple flowers, and thousands of young people, families with strollers and children, on bikes or afoot, trailed the presidential motorcade from the Congress building, where Milei was sworn in, to the Casa Rosada, the iconic pink-colored government palace, where he swore in his ministers.

“I am excited,” Johnathan Suárez, a 30-year-old in a dapper white shirt and khakis, told me. “It’s been too many years of decadence, and we are hoping Milei will change our country for the better. Of course, it won’t be overnight.” Suárez is a carpenter and furniture designer, and said he was aware that his company could go under if Milei decides to open imports, as he has signaled he’d like to, pleading to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, whose charter requires member countries to enforce an open, free-market economy. When I pointed out that possibility, Suárez shrugged and smiled.

At the end of the asado with my family, the arguments had burned out like the fire on the grill, and one of my younger in-laws tried to extend what he thought was an olive branch: “I hope it all goes well for this government.” There was a moment of silence before one of my sisters-in-law curtly replied. “No. I hope it does not go well for him! Because if it does, that surely won’t bode well for the rest of us.”

More from The Nation

This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation. This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation.

The Iranian people are caught between severe domestic repression and external powers that exploit their suffering.

How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class

Olympique de Marseille shows that if fans organize, a team can fight racism, keep its matches affordable, and maintain a deep connection to the city.

Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions

The president wants to resume nuclear testing. Senator Edward Markey asks, “Is he a warmonger or just an idiot?’

The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment

The spectacle of Nicolás Maduro’s capture has drawn attention away from the quieter imposition of systems and power networks that constitute colonial rule.

The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next? The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next?

If the US abandons New START, say goodbye to that comfortable feeling we once enjoyed of relative freedom from an imminent nuclear holocaust.

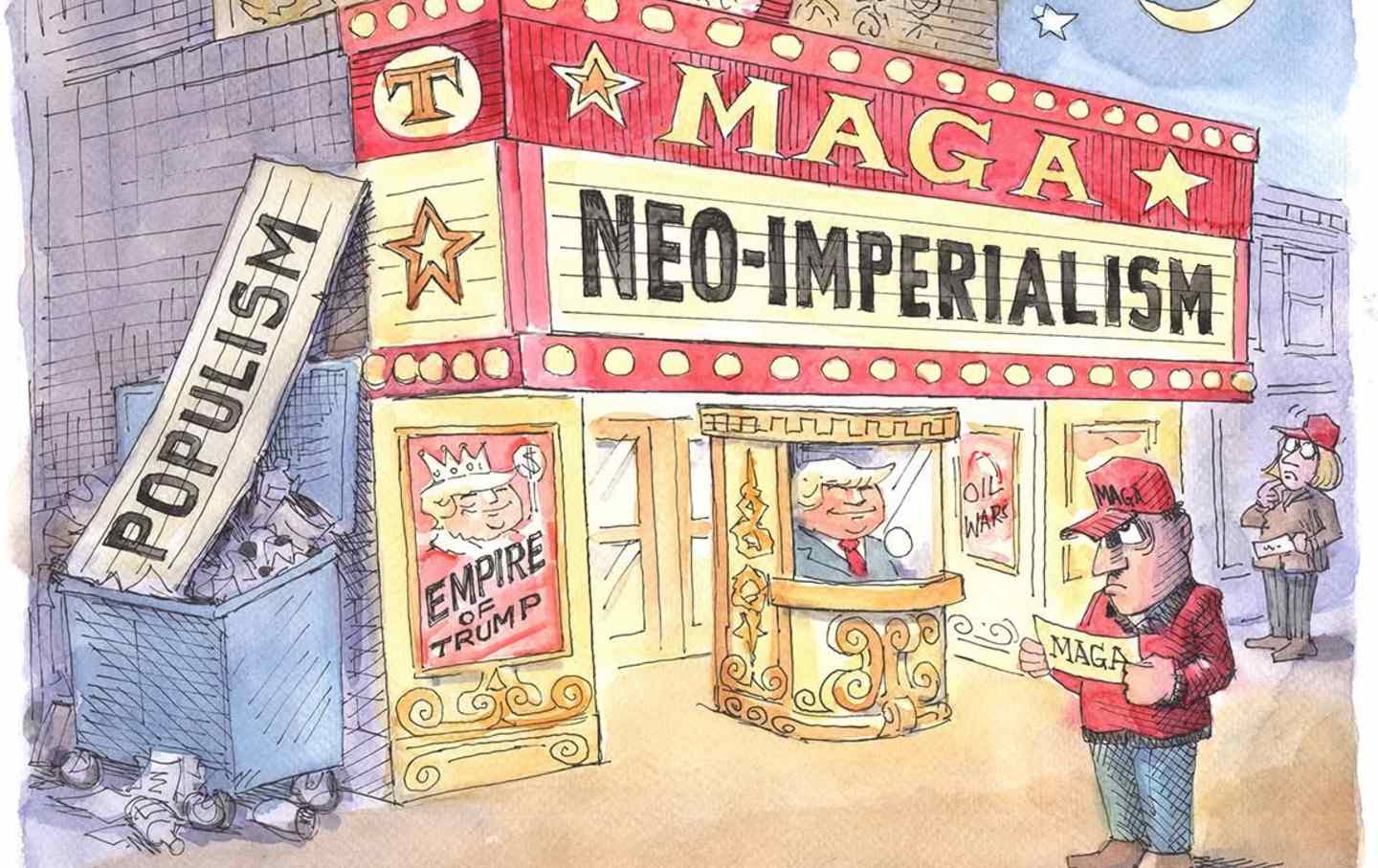

Trump’s Predatory Danger to Latin America Trump’s Predatory Danger to Latin America

The United States is now a superpower predator on the prowl in its “backyard.”