On the 75th Anniversary of the Declaration of Human Rights

How Eleanor Roosevelt’s leadership made her the “First Lady of the World.”

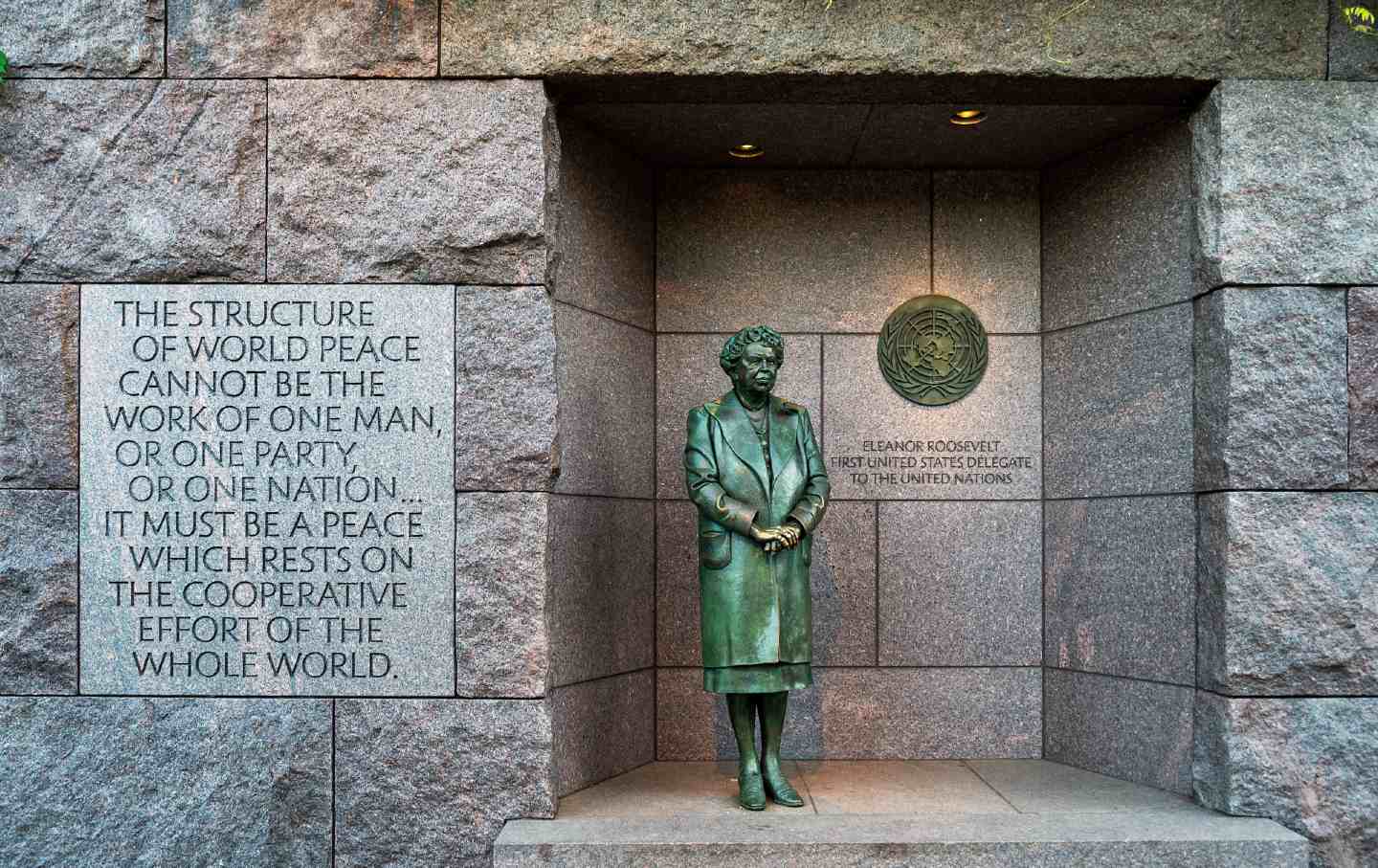

The statue of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt stands before the United Nations emblem at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt memorial.

(John Greim / LightRocket via Getty Images)This Sunday, December 10, marks the 75th anniversary of the ratification of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations. It comes at a time when disregard and contempt for human rights has resulted in barbarous acts of violence around the world.

Brutal wars continue to ravage civilians, especially women and children, in Gaza and Ukraine. We are seeing mass detentions, ethnically targeted killings, and violence against opposition leaders by autocratic governments across the globe. In Gaza City, a UN compound itself was attacked, reportedly injuring and killing a number of evacuees who had sought refuge in this symbolic center of international humanitarian cooperation.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt emphasized that the main purpose of the United Nations was “the establishment of a true peace based on the freedom of man.” This anniversary is an opportunity to commemorate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, remember the freedoms enshrined within it, and commit to pursuing its ideals even as millions of people are still fighting for those rights today.

It should also lead us to remember the leadership of Eleanor Roosevelt, the woman who brought the document into being.

As the longest-serving first lady in American history, Roosevelt left an indelible mark on the country and the world. She transformed the role into what it is today, becoming a public face of her husband’s administration. Throughout his presidency, she advocated for the rights of women, African and Asian Americans, and refugees.

In 1945, the same year her husband died, his successor President Harry S. Truman appointed Roosevelt to the US delegation to the newly formed United Nations. There, Roosevelt took on what she called her “most important task”: the Commission on Human Rights, which unanimously elected her its first-ever chairperson. In that role, she led the development of the document that became the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The declaration itself is a nonbinding collection of 30 articles, enshrining the freedoms that all human beings, regardless of national origin, should have. It prohibits slavery, torture, and exile; pledges freedom of religion, expression, and participation in cultural life; and proclaims that all people should have equal recognition under the law and be free from discrimination.

Roosevelt hoped it would inspire countries to introduce legally binding charters of their own. Indeed, as of today, it has influenced over 80 of the laws and Constitutions that form the world’s legal system for preserving human rights.

Roosevelt turned out to be a formidable diplomat. She worked tirelessly and creatively to facilitate compromise and coalitions between countries with varying ambitions and perspectives on freedom. She was one of the few public figures who could successfully reconcile the seemingly irreconcilable differences of the United States and the Soviet Union. She even persuaded her fellow American delegate, future secretary of state John Foster Dulles, of the rights to food, shelter, and education—principles he believed to be communist—by invoking his Presbyterian upbringing.

Roosevelt’s achievements at the UN were so significant that President Truman deemed her “the First Lady of the World.” Last month, at the memorial service of Rosalynn Carter, the world was reminded of the not-so-soft power first ladies have to shape global politics. Carter went on foreign policy missions by herself, negotiating issues like the Panama Canal and nuclear de-escalation. Like Roosevelt, she was a champion of human rights and global harmony, playing an important role during the 1978 Israel-Egypt talks that led to the peace agreement known as the Camp David Accords. At that summit—which was her idea to begin with—she served as a confidant and crucial backchannel to Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. She, like the global first lady before her, demonstrated that the first step in speaking truth to power is speaking at all.

But words are just that: the first step. Eleanor Roosevelt understood that the United Nations was a flawed but necessary institution. Though we often fixate on the geopolitical intrigue at the Security Council, where countries ceaselessly clash and resolutions are vetoed, some of the most crucial work happens in agencies like the World Health Organization, the International Labour Organization, and the UN Refugee Agency, which draw attention to human rights violations and distribute humanitarian aid. It happens when compassionate leaders like Roosevelt use the unique global platform to guide global discourse, set goals and standards, and draw lines in the sand.

As we celebrate the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it is clear how much farther we still have to go. And as each day brings new atrocities testing the parameters of humanity, remember that human rights are a precondition for all global positive change. “War destroys all human rights and freedoms,” Roosevelt said in a 1951 speech. “In fighting for those, we fight for peace.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda

In his new book Slow Poison, the accomplished anthropologist revisits the Idi Amin and Yoweri Museveni years.

The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day

We may already be on a superhighway to the sort of class- and race-stratified autocracy that it took Russia so many years to become after the Soviet Union collapsed.

Israel Wants to Destroy My Family's Way of Life. We'll Never Give In. Israel Wants to Destroy My Family's Way of Life. We'll Never Give In.

My family's olive trees have stood in Gaza for decades. Despite genocide, drought, pollution, toxic mines, uprooting, bulldozing, and burning, they're still here—and so are we.

Trump’s National Security Strategy and the Big Con Trump’s National Security Strategy and the Big Con

Sense, nonsense, and lunacy.

Does Russian Feminism Have a Future? Does Russian Feminism Have a Future?

A Russian feminist reflects on Julia Ioffe’s history of modern Russia.

Ukraine’s War on Its Unions Ukraine’s War on Its Unions

Since the start of the war, the Ukrainian government has been cracking down harder on unions and workers’ rights. But slowly, the public mood is shifting.