Gaza’s Healthcare System Has Been Set Back Hundreds of Years

Gaza’s doctors are frequently working in conditions not seen since before the Civil War.

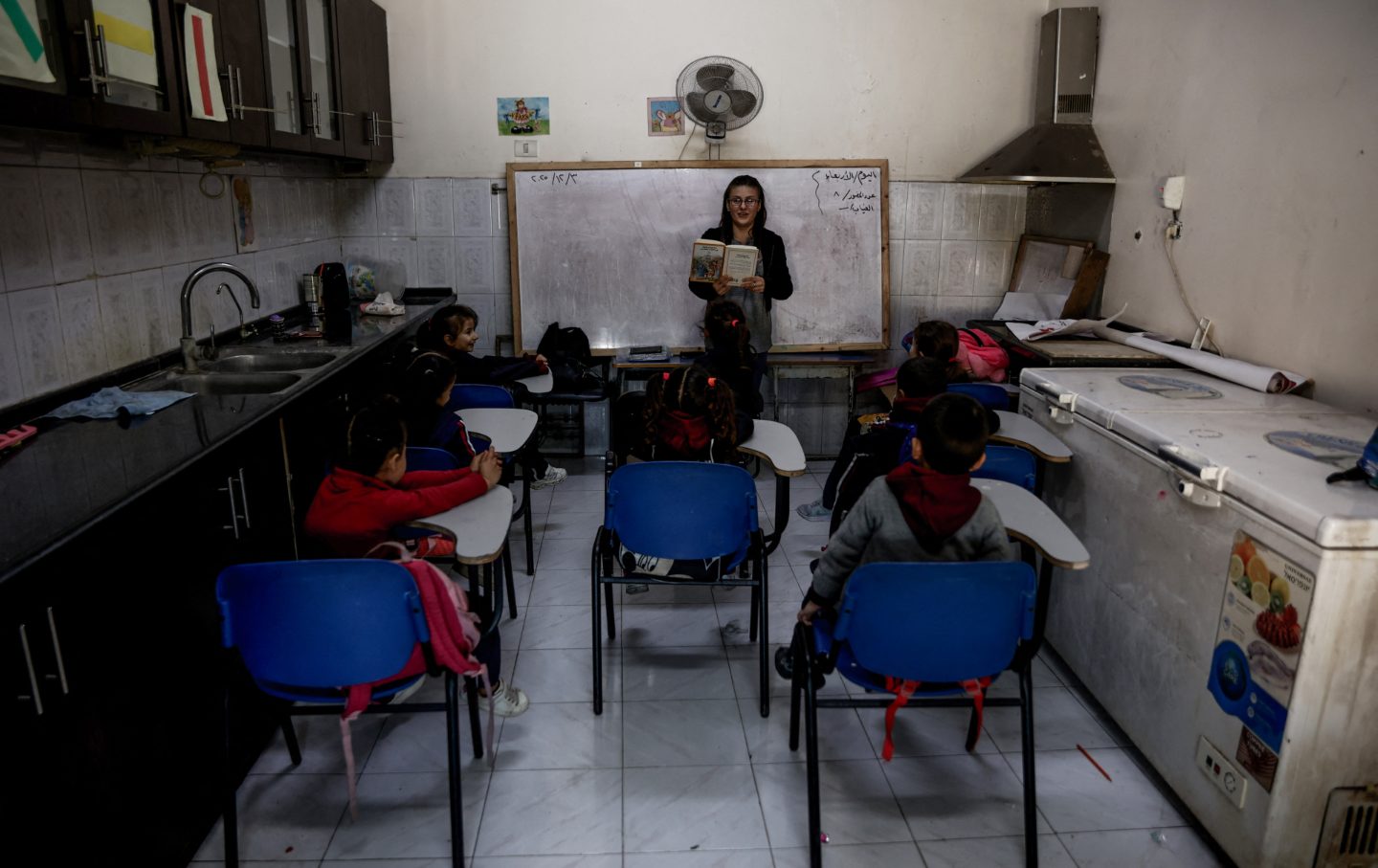

(L) Palestinian doctors work on a patient following the Israeli attack on Nuseirat Refugee Camp in Gaza on September 13, 2024. (R) Surgeons prepare to amputate a patient’s leg at Gettsyburg in 1863.

(Hassan Jedi / Anadolu via Getty Images; SSPL / Getty Images)A week after the Gaza genocide began, I was on an airplane watching the 1989 Academy Award–winning film Glory, which tells the story of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, an all-Black regiment of soldiers who fought in the Civil War. About 10 minutes into the film, there is a scene where Captain Robert Shaw (played by Matthew Broderick) watches in agony as a soldier endures a painful operation in another corner of the room. That depiction of what battlefield medicine must have been like in the mid-1800s has stayed with me, as I have heard horror stories of what practicing medicine is like in Gaza.

For nearly a year, we have heard from doctors who have described the scenes in Gaza as by far the worst they have ever seen. Many recount unthinkable injuries on children; wounds caused by a sniper; missing limbs torn apart by air strikes. Because of the Israeli blockade of Gaza, doctors do not have the equipment to properly dress wounds or to alleviate people’s pain with anesthesia and painkillers. Antibiotics are scarce and there is little to no clean water. Diseases like Hepatitis A and now polio are spreading rapidly—with one child already paralyzed from the latter, prompting an urgent vaccination campaign from the WHO. The population continues to face conditions of famine. According to the Gaza Health Ministry, more than 40,000 people have died. The Lancet estimates that should the assault continue, the total death toll could end up being as high as 186,000 people.

From the beginning, many—including the head of the World Health Organization—warned about the dire health consequences Palestinians would face if this brutality were allowed to continue. This situation was predictable in part because we know from prior conflicts how disease can take advantage of these conditions and spread. And that brings me back to the Civil War.

At the time of the war, scientists were still learning about what caused disease; Louis Pasteur had only conducted his experiments studying the growth of microorganisms in the 1850s, and germ theory would continue to be developed by Robert Koch well into the 1880s. Knowledge of the importance of sanitation and infection control was similarly limited. As a result, about two-thirds of all deaths in the war were attributable to diseases, including typhoid, malaria, and dysentery.

Despite this, the Civil War did bring about improvements in medicine. The first ambulance systems in the United States grew out of the need to transport people from the battlefield to field hospitals during the war. Systems of triage were used to ensure that the people who needed treatment the most urgently received it. Crucially, people received anesthesia (usually chloroform) when undergoing an operation—and it soon became standard practice in American medicine. Only about 254 of 80,000 operations during the war were performed without it. The sounds of agony that were featured in the film Glory were probably not heard on the operating table that often. Soldiers also had access to painkillers like morphine, although this would lead some to become addicted.

The Civil War began more than 160 years ago, so why make this comparison? The simple answer is that many of the conditions in Gaza are similar to the ones found in the 1860s. In fact, the situation in Gaza is worse in some ways than in the Civil War, because medicine has come so far since then.

While the Civil War saw many deaths from disease, this was in part due to a lack of knowledge. Medicine had simply not progressed enough to be able to respond to the needs of the soldiers. Today, there are no such barriers standing in the way of Palestinian doctors. They have the expertise and the skills to save lives. But Israel has deliberately targeted Gaza’s medical infrastructure and prevented vital equipment from entering the war zone. The spread of disease, death, and famine is the direct result of these choices.

Israel has quite literally plunged Gaza into a pre–Civil War medical context. Doctors at Gettysburg and Antietam had anesthesia and painkillers to give to their patients, while some Palestinian children have found themselves undergoing amputations with no anesthesia. During the Civil War, the majority of deaths were attributable to combatants. In Gaza, civilians make up a large proportion of the dead: killed by a sniper’s bullet while evacuating, eviscerated in an air strike, or dying of disease and starvation in a tent.

The Civil War saw improvements in battlefield medicine that would end up advancing the field of medicine as a whole and benefiting countless people. We have made strides in technological and scientific advancements since then that should make many of those deaths a thing of the past. But while we have advanced in those fields, the past 11 months have shown that we have severely regressed in our morality and humanity. World leaders have demonstrated that you can deny lifesaving medicines and equipment in service of the goal of annihilating a people and do so with impunity. What use is our collective knowledge and advancement in scientific and medical technology, if we allow for a world where people are denied access to basic, lifesaving care—where 19th-century medical conditions are allowed to persist because of a 21st-century commitment to cruelty? Progress in such a world is meaningless; for the sake of humanity, this must stop now.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation