The American Ambassador Who Helped Stop a Coup in Chile

Everyone knows how Nixon and Kissinger paved Pinochet’s path to power. The story of Harry Barnes, who played a crucial role in the Chilean dictator’s exit, is much less well known.

The recent 50th anniversary of the military coup in Chile brought renewed international attention to the many villains of the US intervention to overthrow Chile’s constitutional government—chief among them Henry Kissinger, Richard Nixon, and CIA director Richard Helms. Their roles in undermining the presidency of the democratically elected Socialist, Salvador Allende, and then assisting the consolidation of the ruthless regime led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet, remains one of the most renowned cases of official criminality in the annals of US foreign policy.

As the anniversary of the September 11, 1973, coup passed last month, the Biden administration faced a dilemma: how to acknowledge this sordid history without actually atoning, let alone calling more public and political attention to US involvement in Chile’s 9/11. In a small gesture of declassification diplomacy, the administration finally declassified two 50-year-old documents from a long list of still-secret records requested by the Chilean government; US Ambassador Bernadette Meehan quietly attended at least one 50th anniversary commemoration, and Biden dispatched his special emissary on Latin America, former Senator Chris Dodd, to attend the special ceremony on the actual anniversary in front of La Moneda palace. On September 11, a State Department spokesperson released a well-crafted statement citing “an opportunity to reflect on this break in Chile’s democratic order and the suffering that it caused”—while avoiding any reflection on the US role in aiding and abetting those events half a century ago. “This commemoration is also an opportunity for us to reflect on Chile’s courageous return to democracy,” the statement read, shifting the focus away from the beginning of the dictatorship to its ending, after Pinochet lost an October 5, 1988, plebiscite intended to legitimize the continuation of his bloody regime.

To reinforce that point and draw attention to the far more positive history of the US role in the dramatic events of October 1988, this week the US Embassy in Santiago held a special ceremony to honor Harry G. Barnes Jr., who served as US ambassador during the final years of the dictatorship. “The Chief of Mission’s residence will be named ‘The Barnes House,’ according to a US Embassy press advisory, “to recognize Ambassador Barnes’ support of and solidarity with the Chilean people who sought to defend human rights and restore democracy to their country via peaceful and democratic means.”

The event was pegged to the 35th anniversary of the October 1988 plebiscite that marked the beginning of the end of the Pinochet regime. But it will be remembered as the one substantive commemorative ceremony organized by the US government around the 50th anniversary of the military coup itself, refocusing on a time when the United States supported the forces of democracy rather than the forces of dictatorship.

In the long saga of the US role in Chile, Ambassador Barnes stands out as a rare heroic figure. A career diplomat—his previous postings included India, and Romania during the regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu—he arrived in Chile in mid-November 1985 with instructions to promote “the orderly restoration of democracy as speedily as possible.” With radical discontent growing against Pinochet’s dictatorship, the Reagan administration now viewed the regime as a liability, and, even worse, a catalyst for the resurrection of the left in Chile. Indeed, Barnes also received instructions to work toward the “limitation of the influence of the Chilean Communist Party.”

During his three-year stint as ambassador, Barnes aggressively pushed Pinochet to return Chile to civilian rule and end the regime’s ongoing human rights violations. “The ills of democracy can best be cured by more democracy,” Barnes pointedly remarked as he presented his credentials to General Pinochet on November 18, 1985. “I quote[d] Winston Churchill to the effect that nothing is more important than human rights except more human rights,” he recalled in an oral history on his career with the Library of Congress. “Pinochet did not like that.”

Indeed, Pinochet came to despise Ambassador Barnes and banned him from entering La Moneda Palace again. The first major confrontation with the regime came in July 1986, when Barnes attended the funeral of Rodrigo Rojas, the teenage US resident set on fire with gasoline and burned to death by a military patrol during a protest, Pinochet’s police force attacked the procession with water cannons and tear gas; the regime then falsely accused Barnes of inciting a riot by attending the service. After the US Embassy began supporting voter registration drives and the “No” campaign in the lead-up to the October 1988 referendum on Pinochet’s continuation in power, the general denounced US interference and “Yanqui imperialism.” The military-controlled media in Chile took to referring to Ambassador Barnes as “Dirty Harry.” US intelligence officials reported that Pinochet was considering declaring the ambassador persona non grata and “throwing Barnes out of the country.”

Barnes used the close contacts he had established both inside the military and among the pro-democracy opposition to the regime to expose Pinochet’s personal efforts to cover up his military’s responsibility in the case of Los Quemados—the burned ones—which cost Rodrigo Rojas his life and critically wounded a young woman, Carmen Quintana. But his most significant achievement as US ambassador was blowing the whistle on the dictator’s Machiavellian plot to stage an “auto-golpe” on the night of the October 5 referendum if he lost.

In a vain effort to legitimize his regime, Pinochet orchestrated a plebiscite that he believed would make him dictator-for-life. He would be the only candidate in a “Sí” or “No” vote. As the opposition successfully organized the “campaign of the No” and it became clear that Pinochet would lose, he developed a plan to suspend the vote count, use his intelligence agents to assault pro-democracy forces in the street, annul the plebiscite, and declare martial law. “I am not leaving, no matter what,” Pinochet told his subordinates, according to US intelligence sources.

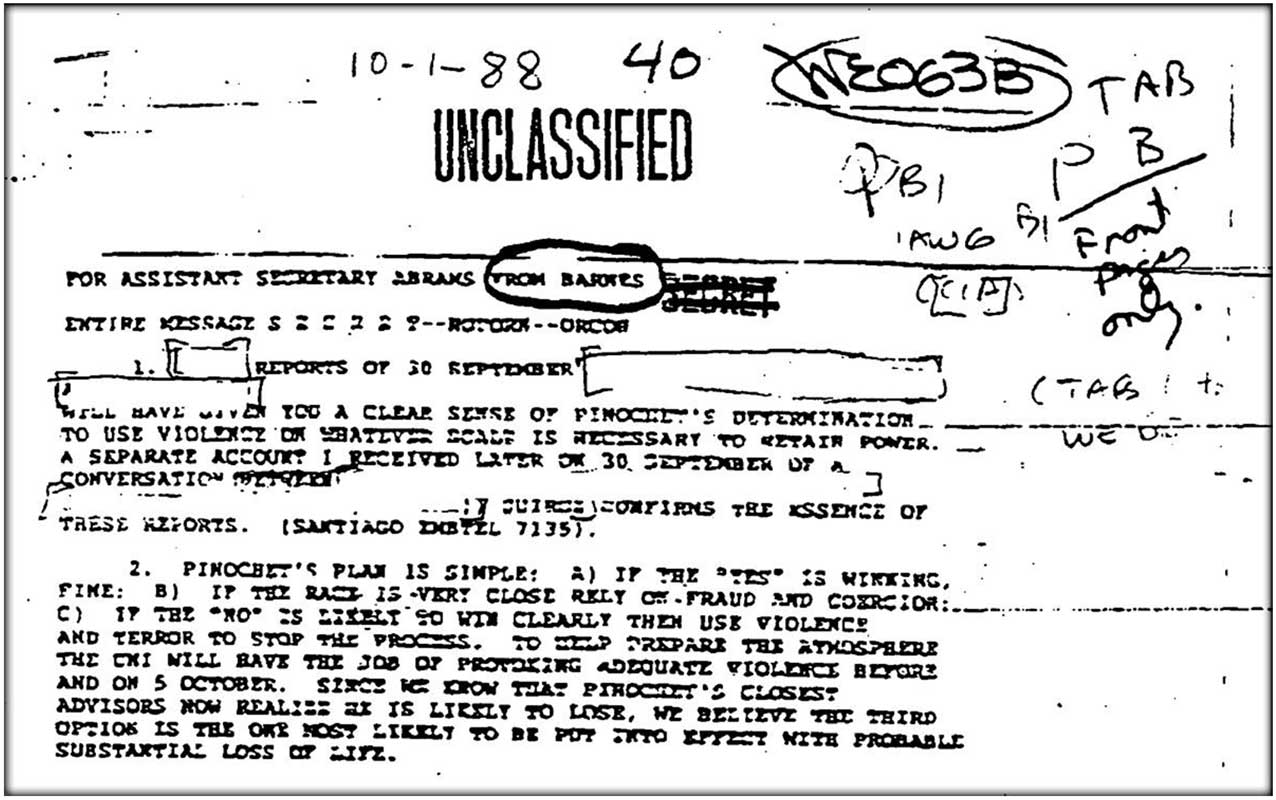

In a secret cable a week before the referendum, Ambassador Barnes warned Washington that an “auto-golpe” was possible. “It cannot be ruled out, and we must be prepared to react to it, and swiftly, while there is still a chance it might be reversed,” he reported to Washington. Once Barnes received concrete intelligence on Pinochet’s plan, he sounded the alarm loud and clear. US officials now had “a clear sense of Pinochet’s determination to use violence on whatever scale is necessary to retain power,” he wrote in a secret dispatch on October 1. He predicted “probable substantial loss of life.”

Over the next four days, US government personnel, led by Barnes, mobilized to pressure key Chilean military and diplomatic officials to oppose Pinochet’s planned coup. When the “No” won on October 5 by a vote of 54.7 percent to 43 percent, an “apoplectic” Pinochet called the members of the military junta into his office and demanded that they sign a decree giving him emergency powers to cancel the plebiscite. All of his generals refused. One the most infamous and entrenched dictators in modern times was pushed from power—without a shot being fired.

Thirty-five years later, as Ambassador Meehan unveiled the plaque designating the US residency as “the Barnes House,” she noted that Barnes had “turned this house into a refuge for those who fought for the peaceful return of democracy” in Chile. Honoring his contribution to the end of the Pinochet regime, she reminded the dignitaries and family members gathered at the ceremony, comes at a “global inflection point” when “democracy is under attack around the world.” Honoring Barnes serves as a repudiation of coup plotters from the past and, more importantly, the present, and it memorializes a time when the US worked to thwart a coup, rather than promote one.

More from The Nation

How Taiwan Became the Chipmaker for the World How Taiwan Became the Chipmaker for the World

A new book tells the story of the island-nation’s transformation into a central hub for technological development and manufacturing.

This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation. This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation.

The Iranian people are caught between severe domestic repression and external powers that exploit their suffering.

How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class

Olympique de Marseille shows that if fans organize, a team can fight racism, keep its matches affordable, and maintain a deep connection to the city.

Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions

The president wants to resume nuclear testing. Senator Edward Markey asks, “Is he a warmonger or just an idiot?’

The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment

The spectacle of Nicolás Maduro’s capture has drawn attention away from the quieter imposition of systems and power networks that constitute colonial rule.

The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next? The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next?

If the US abandons New START, say goodbye to that comfortable feeling we once enjoyed of relative freedom from an imminent nuclear holocaust.