Austerity for Immigration

Emmanuel Macron’s unofficial pact with Marine Le Pen.

Two-thirds spending cuts, one-third tax increases: It’s the ratio that newly appointed Prime Minister Michel Barnier is trying to sell, as he maneuvers a belt-tightening 2025 budget through France’s divided parliament. “Our colossal financial debt is the real sword of Damocles above us,” the 73-year-old premier said in his first speech to the National Assembly on October 1, eyeing upwards of €60 billion in deficit reduction for next year alone.

Fiscal tightening has rapidly become a dominant theme in French politics, with a host of international and domestic bodies warning the country over its budget deficit. As a percentage of GDP, France’s deficit is likely to increase to over 6 percent in 2024, the result of exceptional spending measures enacted during the Covid-19 and energy crises coupled with a spate of tax cuts. This summer, the European Commission put France in so-called excessive deficit procedure for exceeding the maximum 3 percent debt-to-GDP ratio stipulated by the EU treaties.

Barnier and his cabinet now pledge to return France to that level by 2029, calling for several years of protracted austerity in a country preoccupied by already underfunded public services and widening economic inequality. The full outlines of Barnier’s budget have not yet been made public, but the tax increases being considered include temporary levies on the highest earners (0.3 percent of the population, according to the government’s own estimates) and France’s largest corporations. The bulk of the effort is to come from spending cuts, however. These could include a momentary freeze on retirement disbursements, an increase in healthcare copays, the non-replacement of retiring state workers, and cuts to the employment ministries and municipalities. An initial outline of the 2025 budget is expected to be presented in cabinet on October 10.

The push for fiscal retrenchment brings to a close the political uncertainty of this past summer, when snap parliamentary elections resulted in the first-place finish of the left-wing New Popular Front. Formed in the aftermath of President Emmanuel Macron’s June 9 dissolution of the National Assembly, the left-wing alliance ran on a program of wealth redistribution, reinforced state services, and public investments in the green transition. The NFP went on to dash expectations of an imminent victory of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National and emerged as the largest seat-holder in the lower-house, seemingly opening the door to a left-wing government.

Because the alliance was far from the 289 votes needed an absolute majority, Macron was not bound to accept the bloc’s pick for premier. Eager to keep his pro-business agenda intact, the president was firmly opposed to the possibility of an NFP government. He brushed aside the alliance’s nominee, Lucie Castets, before appointing Barnier, formerly the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, in early September.

For Macron, a Barnier premiership was the lowest-common-denominator alternative. A member of the conservative Républicains, Barnier finds himself at the head of a governing coalition of erstwhile enemies, bringing together the parties of Macron’s previous coalition and the center-right opposition. Even combined, Macron’s partners and his new Républicains allies barely hold over 200 seats in the National Assembly, just ahead of the 193 seats controlled by the NFP.

On Tuesday, October 8, the new prime minister survived a first no-confidence vote, with the 142 deputies aligned behind Marine Le Pen and her far-right allies opting to prop up the new government. It was characteristic of the shaky road that lies ahead for Barnier, who will need to keep his own coalition and multiparty cabinet together while assuaging Le Pen.

Even the premier’s overtures towards modest, temporary tax increases have seen a boiling over of tensions within the minority coalition in power. Macron’s allies have claimed that tax increases are a red line—even if the swelling of the budget deficit is in large part a result of Macron’s unfunded tax cuts adopted since 2017. These include the whittling down of a tax on large fortunes to a charge on real estate portfolios, the creation of a lowered flat tax on capital gains, and a slashing of the corporate tax rate to from 33.3 percent to 25 percent. When he left office in September, outgoing Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire boasted of the cumulative €55 billion in reduced taxes that he oversaw, warning that any reversal would mark a serious threat to businesses.

The scuffle is likely little more than a fight for optics between warring parties that find themselves momentarily sharing a cabinet and governing coalition. The Républicains, formerly the dominant party on the French right, have for years clamored over taxation, with all state liabilities on revenues hitting 43.2 percent of GDP in 2023. For legacy purposes, Macron and his allies also want to allay anything that would appear to be a permanent break from the pro-business credo. Yet it could also be politically suicidal not to maintain the façade of balance. Temporary windfall taxes on large corporations and the highest revenue earners is an easy price to pay for the long-term, permanent squeeze on public spending and services viewed as the only way to restrain the deficit.

Seeking to improve the far right’s image in business circles, Le Pen also has an interest in toeing the line on economic policy. In response to Barnier’s general policy speech on October 1, Le Pen promised “to give [the PM] a chance, however slight.”

In return, the new premier has to be careful to curry favor with Le Pen, whose support will be crucial if Barnier is to survive in the coming months. The main olive branch up to this point was the appointment of the hard-right Républicains Senator Bruno Retailleau as interior minister—a job that includes domestic policing and immigration policy.

Retailleau is known to be vying to leave his mark on the county’s immigration system, perhaps through yet another omnibus reform law. This could be the chance to revive many of the harshest elements of a bill passed last winter with votes from both the Macronist coalition and the Républicains and Rassemblement National opposition. In January, parts of the law were thrown out by the Constitutional Council, however, causing uproar from the far right over judicial oversight and the hindering of parliamentary power. Open to a constitutional reform to allow harsher legislation on immigration, Retailleau has in recent weeks warned that a “multicultural society brings with it the risk of becoming a multiracial society” and that there’s nothing sacrosanct about the “rule of law.”

Macron and Le Pen—with Barnier as arbiter—could well work out some bargain over immigration and fiscal austerity. But new elections are still probably only a matter of time. Le Pen has come out in favor of new elections as soon as next summer when, constitutionally, the National Assembly can again be dissolved.

Until then, the New Popular Front will probably be watching from the sidelines. Denouncing Macron’s refusal to consider an NFP government, the left will try to drum up popular opposition, although the first union marches and party-organized protests in September and October have been calm affairs. In the months ahead, the NFP’s most important challenge will be preserving its unity, containing the centrifugal tendencies in both the left-wing France Insoumise and the centrist Parti Socialiste. A wing of the center-left establishment—mainly figures not in parliament, revealingly—dreams of scuttling the alliance and drawing the centrist elements of the NFP into an illusory pact with Macron.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Even if unity can be maintained, the NFP is still struggling to pierce its ceiling of support in the broader population. For all the fireworks this summer, the electorate seems frozen in thirds and has largely remained so since 2017, with three blocs—a shaky left and center and Le Pen’s rising far right—jockeying for power. But maybe there’s a silver lining to Macron’s unofficial pact with Le Pen. The NFP really now is the only alternative.

More from The Nation

This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation. This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation.

The Iranian people are caught between severe domestic repression and external powers that exploit their suffering.

How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class

Olympique de Marseille shows that if fans organize, a team can fight racism, keep its matches affordable, and maintain a deep connection to the city.

Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions

The president wants to resume nuclear testing. Senator Edward Markey asks, “Is he a warmonger or just an idiot?’

The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment

The spectacle of Nicolás Maduro’s capture has drawn attention away from the quieter imposition of systems and power networks that constitute colonial rule.

The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next? The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next?

If the US abandons New START, say goodbye to that comfortable feeling we once enjoyed of relative freedom from an imminent nuclear holocaust.

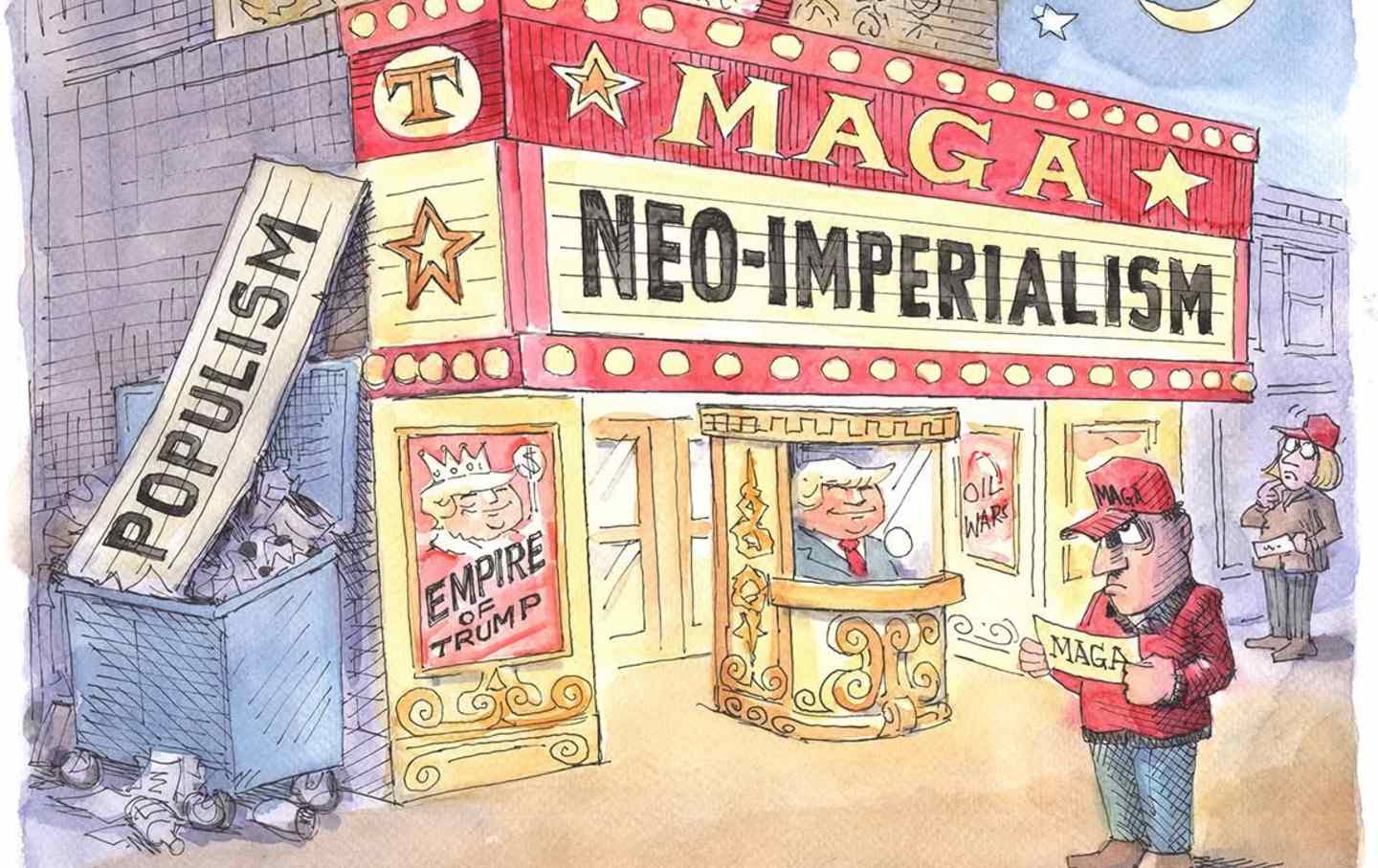

Trump’s Predatory Danger to Latin America Trump’s Predatory Danger to Latin America

The United States is now a superpower predator on the prowl in its “backyard.”