“We are not going to go back until they repeal these laws. For us, it is a life-and-death situation,” says 62-year-old Harpal Singh at Singhu, which has become the epicenter of farmer protests and borders Delhi and the neighboring state of Haryana. He seems unfazed by the bitter cold of this region’s typically harsh winter, whose thunderstorms and rain have contributed to the hardship and subsequent deaths of over 140 protesters, according to the farmers’ estimation. National broadcast media outlets have been on overdrive to paint protesting farmers like Singh as “anti-national” and “secessionists,” while the prime minister has not addressed the farmers even once since November 26, when they began arriving at Delhi’s borders from villages across the northern and northwestern states.

After the “tractor march” by farmers on January 26 (India’s Republic Day) became violent, with clashes between the police and protesters at the iconic Red Fort in the heart of Delhi, the vilification of the protesters on social media and a section of mainstream media became shriller. Since then, the Modi government has begun slapping cases on protesters and arresting journalists considered inconvenient by the government, and it has cut water supply, electricity, and Internet access to the protest venues. Long-distance trains headed to Delhi were delayed or canceled, and not allowed to halt in any of the Delhi stations.

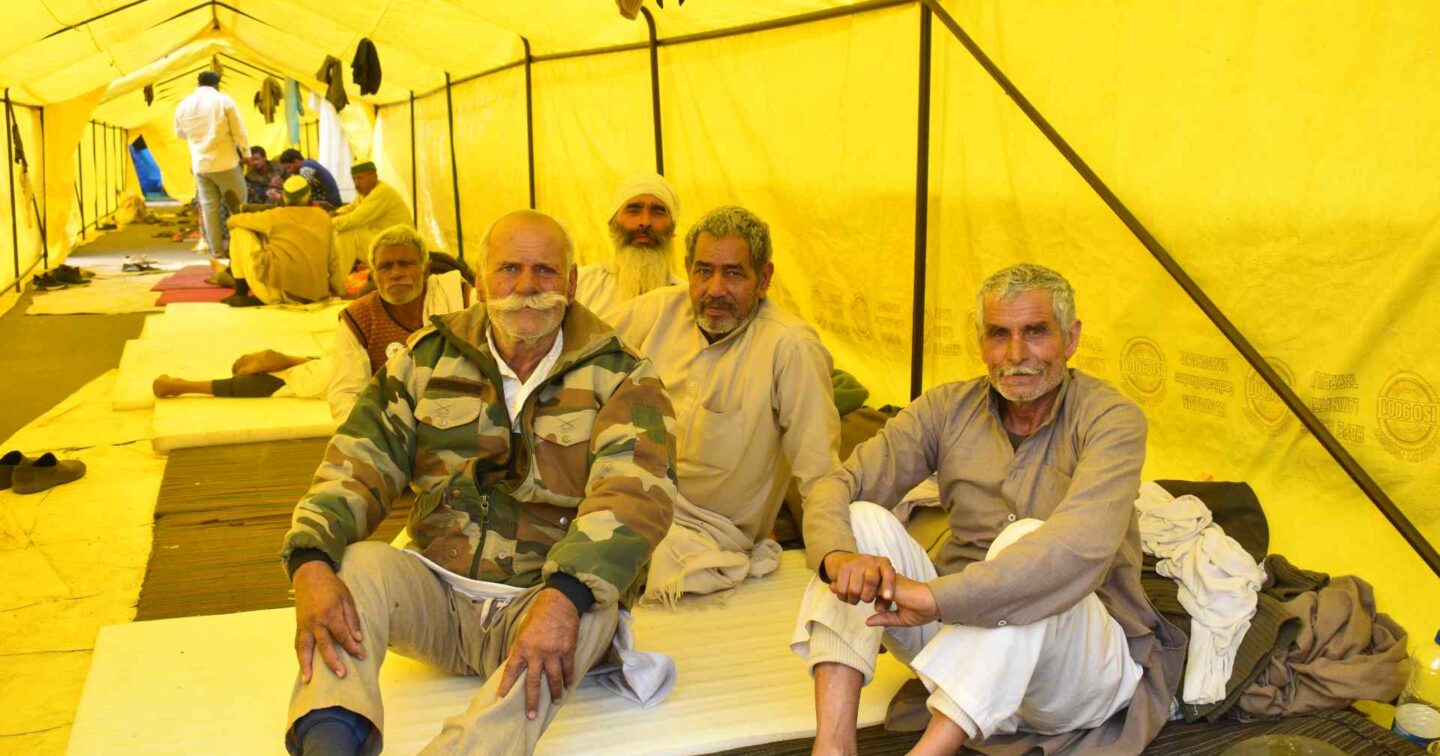

Singh says that, as with all such crowded events, the most difficult part is to get access to toilet facilities. The rest is fine, he adds stoically, confirming that the communal kitchen at Singhu works from early morning until late night, using water from a tube well the protesters have dug. They sleep in makeshift tents with blankets and heaters donated by supporters. He had come three weeks ago to this venue, which is one of the three main sites of the ongoing strike and is playing host to an uncountable number of men, women, and children of all ages, from infants to octogenarians. The other protest sites are Tikri and Ghazipur. “The new laws are not good news for farmers, mainly for those like me, who own just a few acres of land,” he explains. This is why the protesters are not returning to their villages even after the government agreed to put the laws on hold for the next one and half years during their talks with farmer leaders.

Although the country’s agricultural trade system has many problems, the new legislation is considered counterproductive by many noted economists, including the likes of Jean Drèze and Kaushik Basu. The new laws, for the first time in India, allow for wholesale purchase of farm produce outside the state-owned regulated markets in states where those markets (organized under the Agriculture Produce Market Committee, or APMC) are the mainstay for farmers. Drèze, a Belgium-born naturalized Indian citizen who has collaborated with the likes of Amartya Sen, Nicholas Stern, and Angus Deaton, says the new policy effected in the name of reforms will push farmers from “the frying pan to the fire.” Basu, a Cornell professor and former chief economic adviser of India as well as former chief economist for the World Bank, is worried that in its new bouquet of laws, the government hasn’t put in place any risk-mitigation provisions to protect small farmers, but only those to help “friendly” capitalists.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The new markets or “trade areas” that are proposed will fall under the control of the federal government. Buyers at these unregulated markets will not need licenses, and will also be exempt from paying any taxes or fees. The traditional APMCs are run by state governments through licenses, and buyers have to pay taxes and fees to purchase agricultural produce.

Farmers fear that, given such a choice, fewer traders will buy produce from APMCs, which will die a natural death as more and more buyers choose the tax-free new markets run by corporations. Once that happens, farmers aver, they won’t get the minimum support price (a form of market intervention by the government in case there is a sharp fall in prices of select agricultural produce) that APMCs offer, and corporations will fix and manipulate prices. This will result in distress sales, leaving farmers at the mercy of corporations, they contend. Worse, they are also worried about a provision in the new laws that prevents farmers from approaching the courts to seek redress of their grievances against corporations or even state and federal governments.

The government, for its part, claims the new laws will help farmers in unimaginable ways and unshackle them from their miseries, though these benefits have not been clearly spelled out or explained to the farmers by any government official so far. Agriculture in India accounts for around 17 percent of India’s GDP but employs more than half the country’s work force. Most farmers are debt-strapped, and many of them take their own lives to escape from the pain of their existence. At least 10,281 people involved in the farm sector ended their lives in 2019, according to a report by the National Crime Records Bureau.

What actually happened at the Red Fort?

Exactly two months after they began their agitation by occupying the roads to Delhi in multiple locations with trolleys, tents, and trucks, the farmers went on a pre-announced rally to Delhi on tractors and on foot. Some of them deviated from routes assigned by the police and headed toward central Delhi while the ceremonial Republic Day parade, attended by Prime Minister Modi and other dignitaries, was still on.

These farmers did not disrupt the parade or venture toward Rajpath, the large boulevard connecting the presidential palace and the India Gate war memorial, where the parade was in progress. But they managed to move northward and laid symbolic siege to the iconic Red Fort, the historic 17th-century monument, the largest in Delhi, where the prime minister of the country hoists the national flag and gives a speech on the country’s Independence Day on August 15.

As if on cue, their transgression was immediately lapped up by the government through the tentacular power of its social-media brigade. A section of pro-government media, especially TV channels, began to brand the erring farmers as terrorists, hooligans, and supporters of the outlawed Khalistani (Sikh) secessionist movement, a charge that has been hurled at them from the start of the protests.

That a public demonstration by frustrated farmers—who had been protesting the proposal to enact these three new laws since June 2020, and then the laws themselves since September in the confines of their states, and outside Delhi since the end of November—would create minor disturbances in the capital city was to be expected. But instead of questioning the intelligence failure and lack of preparedness by the police and paramilitary forces despite their having had ample advance notice, a large section of the media went on a 24/7 blitzkrieg against the farmers. Ignoring completely the hundreds of thousands of peaceful protesters who followed the permitted route for their tractor rally held on the city’s outer rim, the pro-government media focused entirely on the small fraction who had broken ranks and barged into the Red Fort, which was once the residence of the Mughal royal family.

The scene at the Red Fort was indeed regrettable, with violent clashes in which several police officers and farmers were injured. One protester died while trying to break through the barricades using his tractor, which overturned (some farmers say he was shot in the head by the police, who contest that claim). Journalists and politicians who had tweeted that the protester was killed have attracted sedition cases. The Times of India reported from the dead protester’s hometown in Uttar Pradesh state, quoting his grandfather saying he saw the bullet wound on his grandson’s head.

The farmer leaders—who had been holding marathon talks with the government to resolve the months-long deadlock, and who are part of an umbrella unit of 40 farmer unions called Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM, loosely translated as United Farmer Front)—immediately condemned the belligerent youth who broke barricades and took an unassigned route. By evening, farmer leaders were able to persuade the protesters to return to the edge of Delhi where they had been camping.

The leaders of the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS), which is part of SKM, immediately put some tough questions to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, which controls the internal security apparatus of Delhi. “Why did the police go against the route plan agreed with the SKM leadership and allow an alternate route to a small section, which was allowed to reach the Red Fort?” they asked in a statement on January 27. Meanwhile, it has come to the fore that the team that hoisted a Sikh religious flag atop the Red Fort was led by one Deep Sidhu, who had been refused entry to SKM’s protest venues and who was known to be close to the BJP in Punjab. In this context, AIKS has alleged a “sinister conspiracy” by the ruling government to discredit the farmers.

Criminalization of dissent and branding of rivals as anti-nationals is a growing trend in India, where civil liberties have in recent years been routinely curtailed by the Modi government. Since Hindu nationalist Narendra Modi came to power, in 2014, various sections of the population, from students to Muslims to human rights activists, have been the victims of smear campaigns by the government and pliant media over their ideological opposition to the Hindutva politics of the ruling BJP. The crackdown on protesting students and Muslims has been exceptionally brutal. Those who have raised their voices in support of indigenous populations and Dalits have been branded as “urban Naxalites” and thrown in jail through the invocation of draconian laws (the Naxalite rebellion, a rural Maoist insurgency that began in the late 1960s, has influence over pockets of eastern, central, and the southern India).

Branding protesters as Khalistanis, who demand a separate Sikh nation, appears to be part of the Modi government’s modus operandi, even though farmer leaders have consistently denied any association with such elements. But the charge is serious, since many of the protesting farmers outside Delhi are Sikhs. This secessionist movement started in the northwestern state of Punjab in the early 1980s, with violence between its cadres and government security forces claiming 11,694 lives between 1981 and 1993. On June 1, 1984, the government of India launched a major military operation inside the Golden Temple in Amritsar, considered holy by the Sikhs, to flush out militants holed up there. Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the leader of the secessionists, was killed in the attack along with scores of others. In retaliation, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated on October 31, 1984, by her Sikh bodyguard. That was followed by anti-Sikh riots, especially in Delhi, resulting in 3,350 deaths by official figures (unofficial estimates say deaths could be upwards of 8,000).

Besmirching rivals of the government by linking them to the extreme version of their religious faith has now assumed dangerous proportions in India. If the rival is a Muslim, he is branded an Islamist; a leftist student is called a Maoist; and the protesting farmers are accused of being Khalistanis.

Surinder S. Jodhka, professor of sociology at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, reflects on this trend in Indian democracy: “Social movements are an important part of every healthy democracy. Besides articulating popular sentiments, they also mobilize positive energy and social solidarity. They need to be engaged with by the political establishment to build a cohesive society. Unfortunately, our media is always focused on building sensational narratives, which deepen already existing schisms in our society.”

Regarding the consequences of such tireless propaganda favoring whoever is in power, he adds, “Somehow propaganda has come to be seen as the most viable political tool. Besides other problems, it should also soon begin to produce low returns. Popular media losing credibility is not a good thing for any society.” Not surprisingly, all this reflects the fragility of our institutions, including the judiciary. “I hope the political establishment and civil society recognize this sooner than later. Such a relaxed attitude toward such processes would weaken us as a people and as a society,” Jodhka points out.

On tour of Tikri, Singhu, and Ghazipur, it is almost impossible to meet a protester who has neither served in the armed forces nor had a close relative posted along the border—a vindication of the farmers’ claims that they are here to fight for their rights, not to wage a secessionist battle against the government. The presence of large numbers of women and children—notwithstanding the physical discomforts of being away from home and in crowded surroundings in chilly weather—would be discomfiting to any ruling government. Instead of engaging with these protesters, the government has now decided to restrict Internet services in protest venues, which will affect the supply of necessary goods, including medicine, which is especially critical for the elderly. This is the second time that Internet access has been curtailed in the capital city, the first time being almost exactly a year ago, when students and civil society spoke up against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), a new law that some say discriminates against Muslims. Internet access was also restricted for a few days in parts of the neighboring states Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, not just for protesters but also residents. Punishing people for exercising democratic rights appears to have become a norm in modern India.

In fact, the welcome given to India’s newest Union Territory is a telling sign of what awaits dissenters across the country. Stripped of statehood through Modi’s 2019 repeal of certain provisions of Article 370, which had given Jammu and Kashmir special status and limited autonomy, Kashmir has had no 4G Internet since August 2019, and only limited periods of 2G access, which has crippled the state’s educational and medical institutions and its economy.

Some commentators are now asking farmers to call off the strike following the drama at the Red Fort. Their argument is that deviants among them gave some credence to the government’s conspiracy theory that Khalistanis are behind the farmer protests. But the farmers I spoke to believe that backing down now would not only spell catastrophe for their livelihoods but would also set a bad precedent for future protesters and embolden what they see as a pro-rich, anti-poor federal administration and its right-wing supporters in the media. Many of them also have another issue at stake: Their Sikh identity has been on display because a majority of the farmer leadership belongs to that religion; retreating now, they believe, would give this community, which is historically known for its valor, a bad name.

Indeed, the farmers don’t see any reason to yield to a no-holds-barred effort to taint them. After all, theirs is the biggest mobilization of people in free India. But after farmers were slandered as trouble-makers, what we saw next were pro-government counterprotests at these protest sites, in which several people were injured. This followed the diabolical pattern seen last year at an anti-CAA protest venue in Northeast Delhi, which led to communal riots that saw 53 people killed, most of whom were Muslims; the burning of mosques, homes, and business establishments owned by Muslims; and hundreds of arrests, mostly of Muslim men.

Even as reports come in of thousands more farmers heading to Delhi to join the protests, the government has dug deep holes on the roads, spiked them in some parts around protest venues to stop the entry of tractors, and erected more concertina wires and cement walls. The government was also successful in forcing Twitter to temporarily suspend the accounts of farmer groups, pro-farmer journalists, and even politicians in India—even as the likes of pop legend Rihanna and teenage activist Greta Thunberg tweeted about the protests to invite global attention to what, according to them, is the battle of right against might.

With every passing year, the Modi government only seems to be perfecting its anti-dissent game plan. But this time it’s up against a hard-working, gritty group of citizens who have come together despite Covid-19, cold weather, and a callous media. Will these men of the soil succeed in outstaring Modi’s massive propaganda machine? The alternative is chilling.