Disinformation and Deception in Tehran and Washington

A series of articles allege that some high-profile Western analysts and aides are working for the Iranian government. Are they spies? Or is someone trying to sabotage their work?

In late September, Iran International, an anti-Iranian regime news website based in London, and the US news website Semafor published bombshell articles that suggested that Iranian agents were operating at the pinnacle of the Washington foreign policy establishment. In the article, a half dozen policy analysts of Iranian descent were named as part of an “influence operation” conducted by the Iranian Foreign Ministry. In the days after, one of the analysts, Ali Vaez, of the International Crisis Group, took to Twitter to suggest that he was the victim of “straight up hatchet journalism.”

A vast trove of hacked Iranian Foreign Ministry e-mails had been passed to Iran International by unknown actors, the articles said. The e-mails supposedly showed that the analysts had colluded with the Iranian foreign ministry under the umbrella of something called “the Iran Experts Initiative.” The articles quoted e-mails from 2014 to imply that something sinister was going on—although there was no smoking gun. The writers claimed that three of the analysts were close to Robert Malley, the Biden administration’s Iran envoy, who has had his security clearance suspended since April, allegedly for mishandling classified information. This Monday, Semafor reported that the Republican-controlled House Oversight Committee was subpoenaing the State Department for information on Malley and Ariane Tabatabai, one of the analysts, who now works at the Pentagon.

The analysts and their institutions took to Twitter to deny that the e-mails showed that they were in thrall to Tehran, but the story continued to reverberate in the media. Fox News had a field day. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens fawned over the “blockbuster” reporting by both outlets. Tablet magazine went even further: “High-Level Iranian Spy Ring Busted in Washington,” a headline crowed, before alleging—without any proof beyond the original articles from Iran International and Semafor—that “Robert Malley helped to fund, support, and direct an Iranian intelligence operation designed to influence the United States and allied governments.” A columnist at Iran International claimed that the operation was akin to a Soviet deception practiced on Alan Wolfe, a member of The Nation’s editorial board in the 1980s.

The Semafor and Iran International articles also had more serious consequences. A group of 30 Republican senators wrote to the secretary of defense about Pentagon analyst Tabatabai. Based on the articles, the senators urged the secretary “to suspend Ms. Tabatabai’s security clearance immediately pending further review.” (So far, her clearance has not been suspended and the Pentagon has been unreserved in its support, saying that she had been “thoroughly and properly vetted.”)

But what had Semafor and Iran International actually revealed? Not much, it seems. A careful reading of both articles showed the analysts being solicitous of Iranian officials in order to get interviews but not disloyal or unethical. Many of the leaked e-mails were quoted in snippets, so it was hard to gauge their context. Some of the language might not have been phrased in the way journalists, who strive to be impartial, are expected to approach a foreign official, but analysts at Crisis Group and other NGOs told me that analysts often use their nationality and prior experiences to seek interviews.

There were, however, two more serious claims in the article. One of the e-mails purports to show Adnan Tabatabai, another analyst (no relation to Ariane Tabatabai), offering to ghostwrite op-eds for the Iranian foreign ministry, although Tabatabai denied he had ever done so. Iran International wrote that it had commissioned a “forensic study of e-mail headers” that indicated the e-mails with his purported offer were genuine. (The outlet declined to respond to queries and Semafor declined to provide the forensic study.) Without seeing the study and the original e-mail, it is hard to evaluate such claims, but several experts told me that sophisticated hackers can alter e-mail headers and metadata to falsify their points of origin.

Another e-mail quoted by both outlets suggested that Arianne Tabatabai sought permission from Iranian officials to travel to Israel. The articles then said that it was unclear that she had visited Israel after the e-mail. Ori Rabinowitz, a senior lecturer of international relations at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem confirmed to me that Tabatabai had traveled to Jerusalem in 2018 to review an archive of Iranian nuclear documents. “The Israelis invited her because she is trusted and respected,” Rabinowitz said in an e-mail.

“People say you shouldn’t even speak to the other side. Well, as Crisis Group, we talk to all sides,” Joost Hiltermann, MENA program director at International Crisis Group, where two of the named analysts currently work, told me. “I didn’t see anything in the e-mails that I wouldn’t say to a government official.”

Many of the analysts named in the original articles spoke to The Nation to clarify what they said was a misunderstanding at best and a deliberate misreading of the e-mails at worst. Some declined to be interviewed for the record—citing job concerns—but all denied that they were part of any Iranian disinformation operation. They all also pointed to articles they had published critical of Iran’s policies. Only last month, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei denounced a sinister US “crisis group” that he claimed was working to destabilize Iran. “The proof is in the pudding,” one of the analysts said.

All of the analysts told me that the Iran Experts Initiative was a loose grouping of Farsi-speaking analysts who pooled together in order to speak to difficult-to-access officials during the Iranian nuclear talks with the P5+1 countries in 2014. E-mails from the time between the analysts provided to The Nation by one of the people named by Iran International and Semafor show they met for breakfast meetings with officials and had informal chats among themselves to discuss the implications of twists and turns in the negotiations.

Dina Esfandiary, one of the analysts who was involved in the decision to pool together to speak to Iranian officials described the group as “incredibly, incredibly informal.” I asked her whether the group was funded by Iran, something that is hinted in the accusatory pieces through the quoting of leaked e-mails. She called the claims risible. “We would fund ourselves through our own research funding,” she said. When some analysts couldn’t fund their travel, they raised money from some European institutions and a European government that the analysts declined to name. “It’s a country that’s one of, if not the oldest US allies in Europe,” was as far as one would venture.

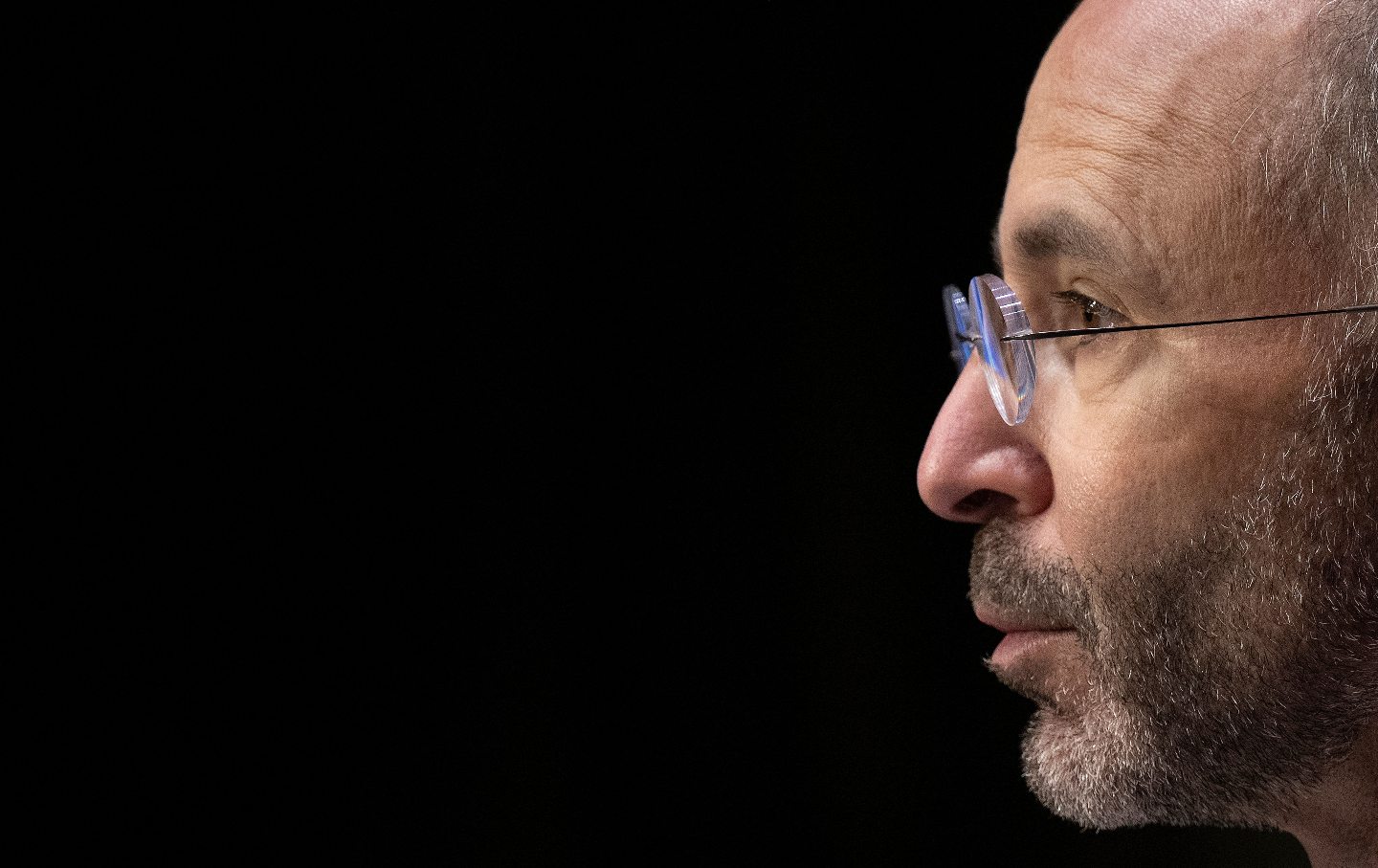

So how had Semafor and Iran International gotten it so wrong? Iran International is an easier case: It’s an anti-Iranian regime outlet with an axe to grind. Semafor, run by former Buzzfeed News editor Ben Smith and the former Bloomberg Media chief executive officer Justin Smith, is more widely respected. Perhaps a clue is the inclusion of Malley, the Biden administration advisor, who was also the victim of an Iranian hack earlier this year. Most of the analysts named, apart from Ali Vaez, a Crisis Group Iran specialist, were not particularly close to Malley, although both Semafor and Iran International alleged their proximity, and illustrated their reporting with large photographs of Malley.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Iran International did not respond to multiple requests for comment. A Semafor spokesperson responded by e-mail, saying, “This is one of the biggest stories in Washington right now and we stand behind Jay”—Solomon, the reporter on the piece—“and his groundbreaking reporting on the subject. We have repeatedly tried to contact all relevant parties for comment, and again, urge them to respond and engage directly.”

“This is something that’s pretty easily verifiable: I have zero overlap with Rob Malley at Crisis Group. He left in January. I joined in February. I’ve only ever met him once,” Esfandiary told me, decrying factual inaccuracies in the reporting. Though Tabatabai briefly worked on Malley’s effort to revive the Iran talks at the State Department, she had been hired by someone else and resigned from Malley’s team because “she had a harder line view,” a source close to the story said.

Malley’s attempt to dialogue with Iran has earned him enemies in Washington, where Trump’s rejection of the Iran deal became a point of contention between Republicans and Democrats. “I think that it’s all part of a loosely arranged campaign by people who are against the nuclear deal, who are against diplomacy,” Hiltermann, of the ICG, told me.

Jay Solomon, the Semafor journalist, is certainly someone who has been critical of the attempt to negotiate with Tehran. Solomon worked for The Wall Street Journal until 2017 when he was fired for “violating the paper’s ethical standards.” E-mails of his had been leaked to journalists at the Associated Press showing an uncomfortably close relationship with Farhad Azima, an Iranian-American businessman and sometime arms dealer. “Some of those e-mails look stupid, but I think anyone, if they’re gonna get hacked, they can make you look like a nefarious character if that’s their intention,” Solomon told BuzzFeed News in 2018. (Semafor did not answer specific questions about Solomon or whether he maintained links to Azima.)

So where had the leaked e-mails come from? Iran International had apparently received them, translated them, and then passed them to Semafor’s Solomon. (It has been suggested that they were shopped around Washington by Morgan Ortagus, a former Fox News commentator and State Department spokesperson under Donald Trump, though she has denied the rumors.) Both media outlets worked on the leaked correspondence together, although, according to Solomon’s piece in Semafor, they “produced their stories independently.” One of the analysts told me that the outlets reached out with questions before the summer, and then held the story until September. “The question is, Why now?” Hiltermann pondered.

No one wanted to speculate on whom the outlets had received the e-mails from, and neither Iran International nor Semafor would share them or comment on their source. One person close to the story suggested the e-mails been obtained in a hack of Iranian Foreign Ministry e-mails by the Mojahedin-e-Khalq, a group that is both anti-Iranian regime and anti-US. Others suggested that Iranian regime hard-liners had leaked them to ensure that dialogue doesn’t happen and that the status quo is maintained. (“They are like mushrooms,” an analyst said of hard-line Iranian groups like the Revolutionary Guard, “they grow in the dark.”) But if this was the case, Iran International and Semafor would be unwitting pawns in a hard-line Iranian disinformation scheme. How’s that for a hall of mirrors?

One of the things that all the analysts I spoke to acknowledged is that the 2014 context, when the Obama administration’s policy was to talk to Iran’s government, had been lost in the presentation of the e-mails. “We were speaking about a time when everybody knew that, should this not go through, there would be a new high risk of the war in the region,” Adnan Tabatabai told me. “And in order to avoid that, those who believed in dialogue went extra miles to do so. Criticizing that is totally legitimate, but discrediting, defaming, shaming, et cetera, this is too much.”

Ali Vaez, the ICG analyst, says that he has received multiple death threats in the wake of the publication of the pieces that named him. This is especially upsetting, he pointed out, because he was not able to return to Iran to attend his father’s funeral because of political pressure stemming from his work. “Now I am attacked by my own country, in the US, and all of this because I tried to do something helpful, something to avoid a nuclear standoff ending in war,” Vaez told me. “I still believe that if hard-liners are so determined to bring me down, I must be doing something right.”

After this article was first published, Adam Baillie, a spokesperson for Iran International and its parent company Volant Media, contacted The Nation. “The source of the Iranian Foreign Ministry emails is known to us, but we did not reveal it in order to protect our source,” Baillie said in an e-mailed statement. “Iran International has no axe to grind: we began in 2017 as an editorially independent Farsi-language news channel. We have no affiliation or association with any group, either state, political or social,” Baillie continued. “Our broad coverage of Iranian diaspora opinion in itself can attract much criticism from those in disagreement. The Channel itself holds no position other than accurate reporting of Iran-related news.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from Nicolas Niarchos

Damascus Diary: A New Year in a New Syria Damascus Diary: A New Year in a New Syria

Syrians begin to learn to live without Assad.

Beijing Calls Washington’s Bluff on Strategic Metals Beijing Calls Washington’s Bluff on Strategic Metals

China’s latest export restriction lays bare the complex geopolitics behind President Trump’s proposed tariffs—and the green energy transition.

What Happened to Patrick Masengo Kalasa? What Happened to Patrick Masengo Kalasa?

The longtime advocate for Katangese rights recently disappeared in the Democratic Republic of Congo. His friends fear for his life.

CUNY and Columbia: A Tale of Two Campuses CUNY and Columbia: A Tale of Two Campuses

Why are the City College protesters being charged with felonies that could land them up to nine years in jail—while Columbia students are facing much lighter sentences?

The Police Take City College The Police Take City College

Scores of people were arrested at the City University of New York on Wednesday—a scene "very reminiscent of the 1968 police crackdowns" at Columbia University, said one protester....

The Occupation and Reoccupation of Sciences Po The Occupation and Reoccupation of Sciences Po

Paris has felt surprisingly apolitical these last few months. But something changed: Students occupied one of France’s most elite universities.