It’s Time to Compost the Prison Plantation

How agriculture is used to make mass incarceration seem humanitarian.

At Potosi Correctional Center in Mineral Point, Mo., stone buildings overlook verdant gardens. Prisoners produce vegetables in these so-called “Restorative Justice Gardens.” They’re part of a carefully choreographed attempt by the Missouri Department of Corrections to portray prisons as humanitarian enterprises.

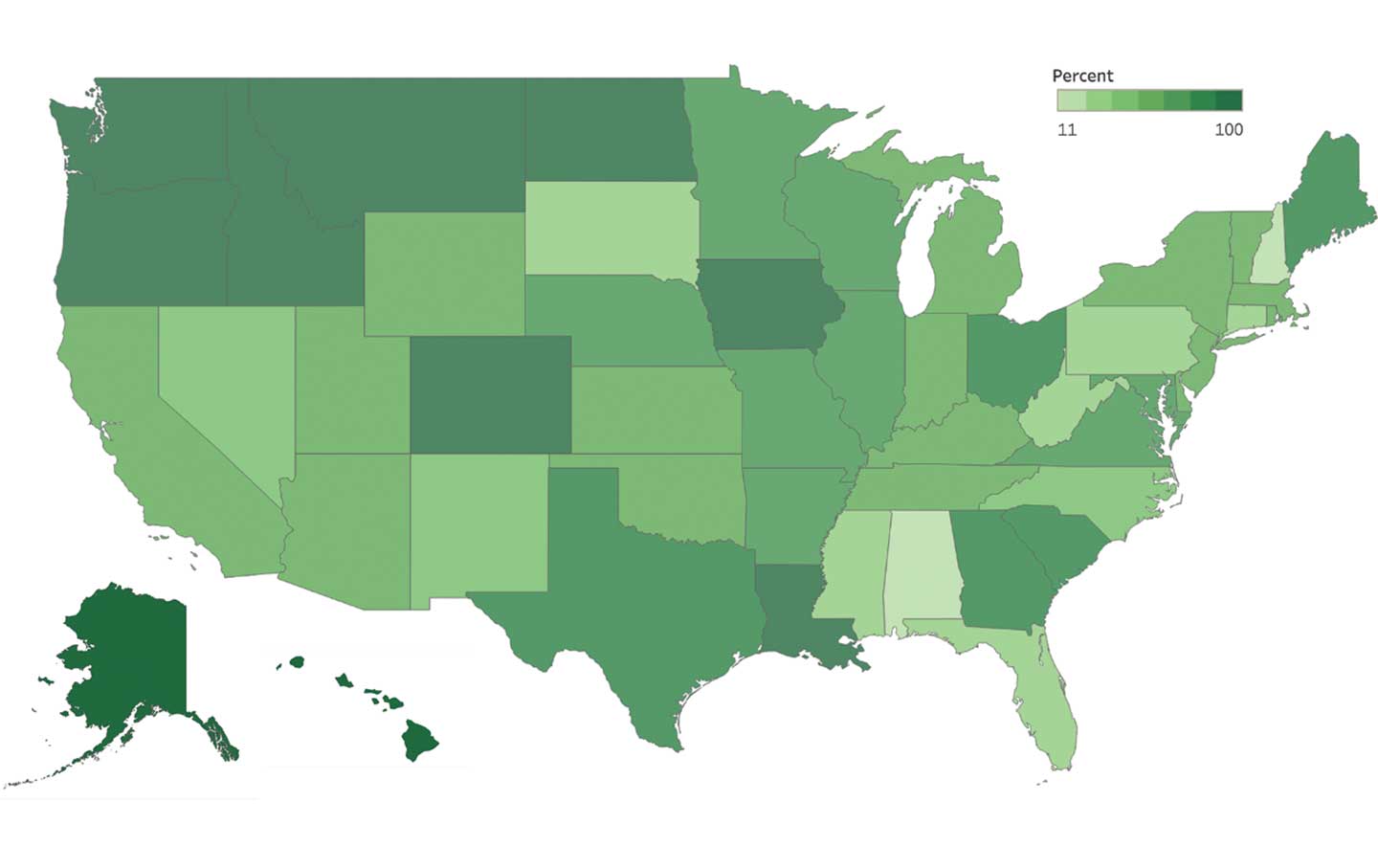

It’s just one example of a nationwide effort to use agriculture and nature to gloss over the reality of mass incarceration. More than 660 state prisons have agricultural initiatives of some kind. But if agriculture “restores” anything, it’s the prison plantation.

Between 2018 and 2023, American prisons sold almost $200 million worth of agricultural products, many of which have made their way into the offerings of major food brands.

Incarcerated workers are typically paid between $0.14 and $1.41 an hour in America.

As cofounders of the Prison Agriculture Lab, we use research to bring to light a practice that helped build the prison system and continues to nurture its existence. We do not want to restore the prison plantation. Our aim is to undermine its legitimacy.

The violence of incarceration has always been sold to the public in some way. It just so happens that in the United States, working the land is vaulted. It’s “God’s work.” As such, agriculture has the power to discipline an underclass—whether with the carrot or stick of hard labor—in need of redemption.

Philosophies of incarceration toggle between commitments to punishment and rehabilitation, a confined spectrum of possibilities that never questions the necessity of prisons. As two sides of the same disciplinary coin, these ideas undergird incarceration as a solution to a host of social problems. In the case of rehabilitation, the carceral humanitarian approach, proponents can claim their strategies better prepare formerly incarcerated people to reintegrate into their communities.

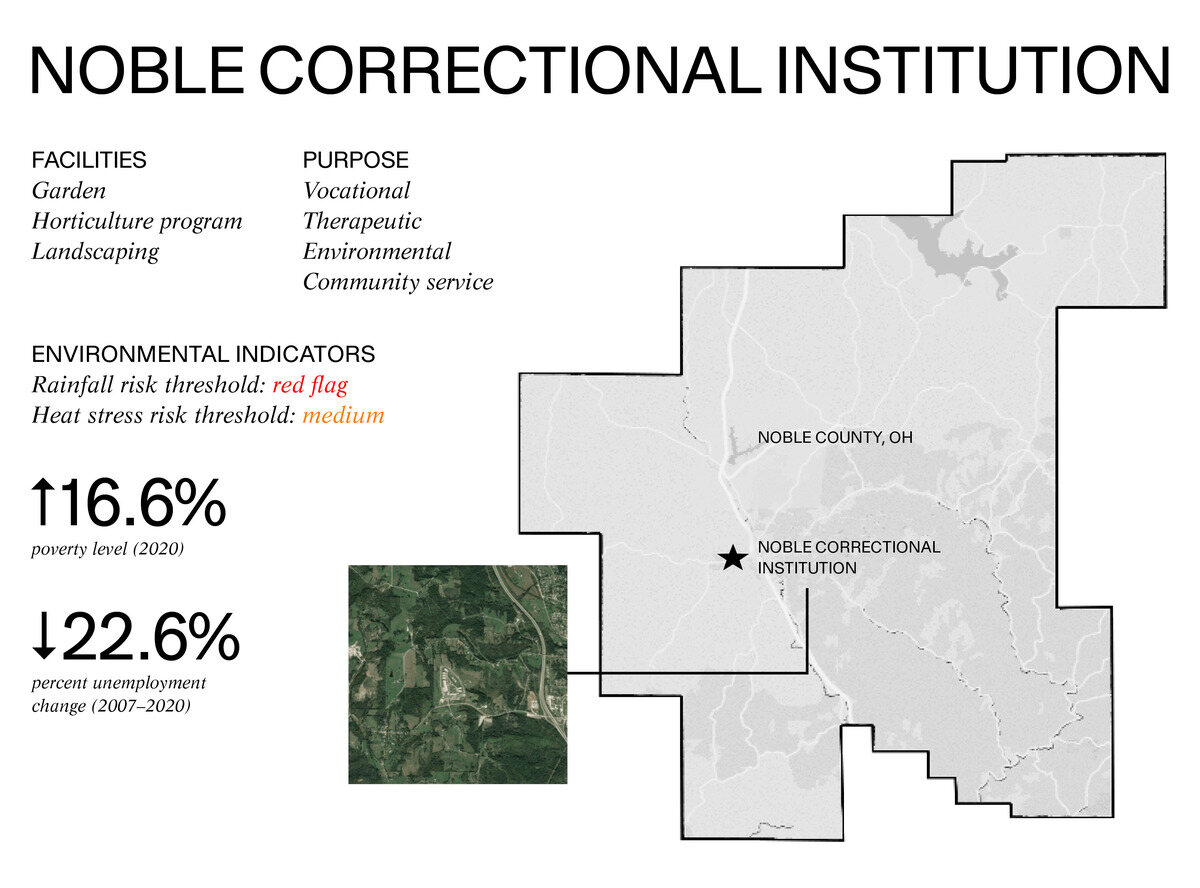

It’s within this paradigm that prison authorities promote gardens and horticultural training programs, to the applause of positive press. Prisoners will be “cured” of their criminal ways. Never mind that incarcerated people generally need to be a lower “security threat” to have the privilege of working with plants. The weaponization of the desire for greater freedom underlies such rehabilitative philosophies.

But incarcerated people don’t need the sanction of the state for their humanity to be realized. Indeed, it’s in taking control of one’s restricted condition where true fugitivity, and therefore freedom lies. Matthew Hahn, formerly incarcerated in California’s Folsom Prison recounts the story about how he and others maintained a secret garden. Although they weren’t allowed to, these men grew and smuggled countless crops, from squash and peas to watermelon and tomatoes. Once inside, this bounty was shared and transformed into meals that reminded prisoners of home.

Or take the case of the “green zone” in Washington State Prison. Modeled on the survival programs of the Black Panther Party, prisoners built rentable garden plots with solidarity economics. For seven dollars, outside the control of prison officials, prisoners could grow food in a part of the yard they repurposed. The money went back into seeds and worms to grow food that was healthier than what was provided in the chow hall.

Meanwhile, prisoners at Minnesota Correctional Facility–Lino Lakes have sought to hold prison officials accountable to a state law that requires prisons to start gardens if there is space and adequate security. There is an abandoned greenhouse of 24 years that prisoners—with the support of Metro State University’s college-in-prison program—successfully campaigned to get reopened and turned into a year-round food production site.

Taken together, these food sovereignty endeavors reveal the agency of incarcerated people to resist disposability under the constant vise of unfreedom.

But the division and control of carceral systems is vast. Take food apartheid. Access to healthy food is segregated through the creation of neighborhoods deemed undeserving. Redlining, racial covenants, public disinvestment in infrastructure, and more produce poverty. The response then is heavy policing, which leads to disproportionate levels of incarceration. Food retailers, like grocery stores, avoid such places. The cycles of abandonment and criminalization continue. Linking such conditions can stoke abolitionist food politics that disrupt the prison pipeline.

In Oakland, Planting Justice uses agriculture to connect people across the free/unfree divide. A third of the staff is formerly incarcerated, many from San Quentin Rehabilitation Center. They work alongside others to tend one of the largest organic tree nurseries in the country, plant community gardens, educate youth, and more. Not only are people avoiding reincarceration with healing horticultural practices, but they are also challenging exploitative conditions like prison slavery.

Across the country in the Hudson Valley of New York, Sweet Freedom Farm operates as a network of farmers, organizers, and abolitionists linking the food needs of low-income people and incarcerated loved ones. The farm produces landrace varieties of wheat, corn, and sorghum, harvests syrup from maple trees, and trains Black farmers, including carceral impacted youth. With the resulting bounty, they deliver food to Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

Sowing the Seeds of Abolition

Growing food in prisons is not going to solve the problems of racial capitalism. The dehumanization and dislocation that feed people into the jaws of the prison system must be directly confronted. From our vantage as scholars and activists, this requires first seeing prison agriculture as a carceral practice, one of many that captures social wealth and funnels it into a punitive system. People are deserving of land and resources before they’re incarcerated. Dismantling prisons is directly related to building new agricultural worlds.

Back in Missouri, there are many overlapping abolitionist efforts that reveal the need to starve prisons of resources so that community vitality and justice can thrive. The recent victory by a community coalition to close St. Louis’s notorious Medium Security Institution (the “Workhouse”) is particularly noteworthy. Breaking down also requires building up. After the murder of Michael Brown, Hands Up United formed to organize against police violence and develop community care programs like Books and Breakfast and the People’s Pantry. There are also food justice efforts to build a Black and brown self-determined food system throughout St. Louis. From the small solo Heru Urban Farming operation and neighborhood City Greens Community Garden to the mission-driven Agriculture for Community Restoration Economic Justice and Sustainability and Rustic Roots Sanctuary, liberatory visions abound.

These experiments in abolitionist living are seeds for a future where people and plants both grow free.

This story was published in collaboration with MOLD, an online and print magazine about designing the future of food.

Data Visualization by Isabel Ling and Kristi Huynh.