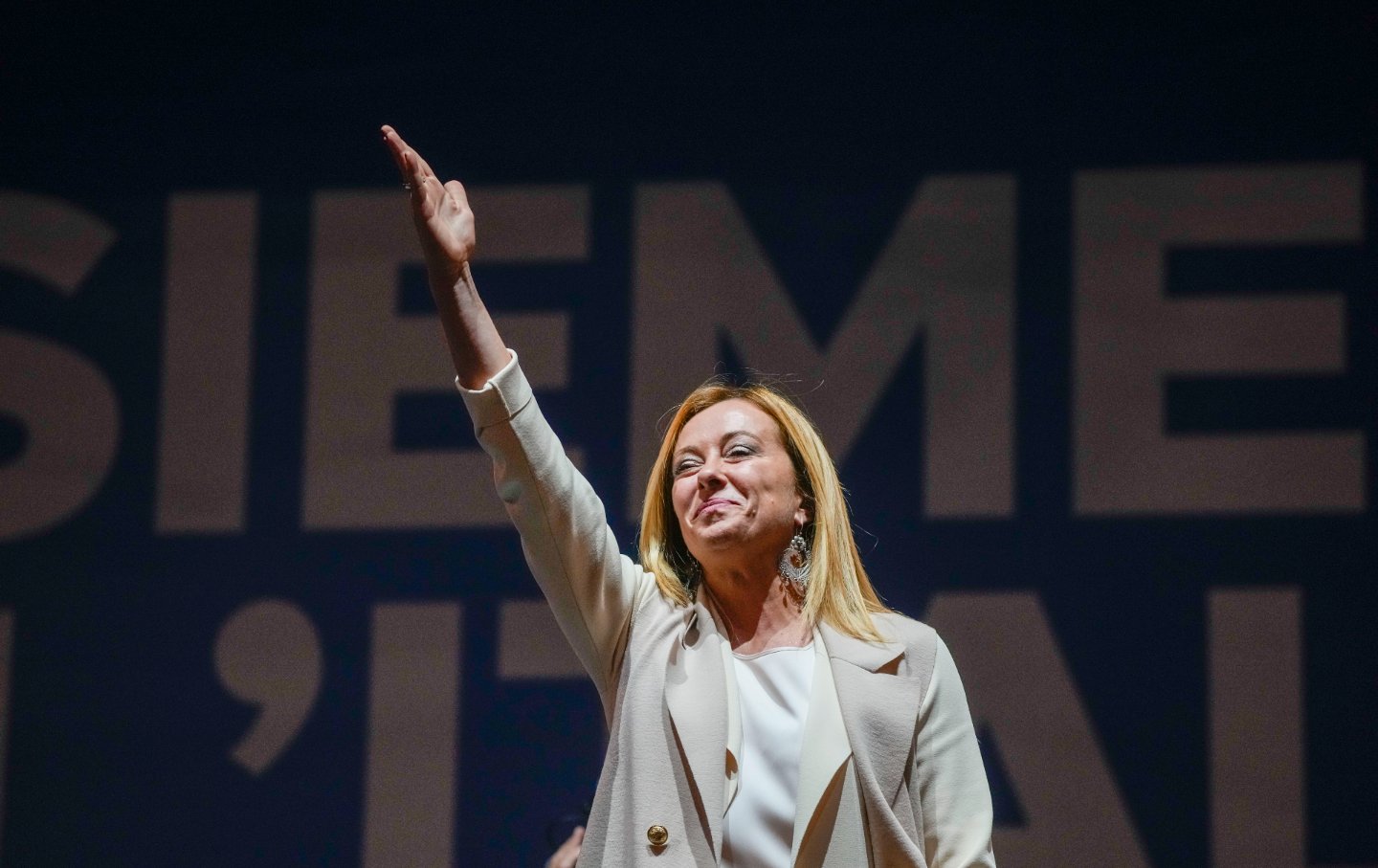

Brothers of Italy’s Giorgia Meloni attends the center-right coalition closing rally in Rome, September 22, 2022.(Gregorio Borgia / AP Photo)

The normalization of Giorgia Meloni has already started, a remarkable process considering that the strong showing of her Fratelli d’Italia (FDI) party, now set to be the dominant faction in the new Italian government, is a terrifying victory for right-wing extremism. Much of the commentary on her political rise is rightly focused on the many warning signs that she’s a political fanatic: The FDI has roots in Italian neo-fascism, Meloni herself has praised Mussolini and autocrats like Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán, and her current politics are based on demonizing immigrants and LGBTQ people.

But if one reads the centrist political analysis, it’s hard not to notice that there are a few highly influential voices who have managed to find a silver lining in Meloni’s political profile. It’s true, these commentators acknowledge, that Meloni’s politics are far-right—but she also shows signs of supporting the existing elite consensus on crucial issues like NATO, the Ukraine-Russian war, and the European Union.

In an editorial that contained some sharp rebukes to Meloni’s xenophobia and demagoguery, The Washington Post made this striking claim: “In fact, it would be a stretch to regard Ms. Meloni, who would be Italy’s first female premier, as a fascist. And, having dropped her former admiration for Russian dictator Vladimir Putin, she has been unstinting in backing NATO’s support for Ukraine.”

The Economist offered a similarly hedged assessment, comparing her favorably to other right-wing Italian leaders like Matteo Salvini and Silvio Berlusconi and claiming that Meloni is likely to work with pro-EU bankers. The magazine added, “There is one more indubitable plus to Italy’s probable new prime minister. Unlike Mr Salvini and Mr Berlusconi, or indeed Ms Le Pen and Mr Orban, Ms Meloni is no fan of Vladimir Putin. Since the invasion of Ukraine, she has been a steadfast and strong voice of support for Ukraine and NATO.” The Economist advised, “Europe must calmly accept Italy’s democratic decision to elect Ms Meloni and help her succeed.” The New York Times published an essay by Italian newspaper editor Mattia Ferraresi that struck the same note, approvingly noting that Meloni is “a torchbearer of Atlanticism and a staunch supporter of NATO.”

These respectable, establishment editorial voices suggest that Meloni has a very easy path toward respectability: All she has to do is toe the consensus line on NATO, the war with Russia, and the EU. If she does, the Western elite will overlook her neofascist history and current scapegoating of minority groups. Italy, by this scenario, will achieve the same status as Egypt or Saudi Arabia: a regime with an unpleasant domestic politics, which can be overlooked for the sake of realpolitik.

If this does come to pass, it’ll be a sad reminder of how quickly Western elites are willing to sideline their often-voiced commitment to democracy. But the ongoing evolution of Meloni from neofascist threat to possible pro-NATO ally is also significant as a story about an important repositioning of the far right. Parts of the global far right, particularly in Europe and North America, are shifting away from the pro-Putin stance of a few years ago.

Reactionary Russophilia has a long history—stretching back before the Cold War interval where the Soviet Union was the regarded with repugnance by most (although not all) right-wingers. In the 19th century, Russia was the capital of European reaction, the nation that had defeated Napoleon and served as the bulwark and protector of monarchies and the old order.

On an ideological plane, Slavophile writers of the caliber of Fyodor Dostoevsky and Konstantin Leontiev were bracing critics of Western liberalism. Even in the era of communist rule, the idea of Russia as a salutary alternative to Western liberalism intrigued right-wing thinkers like Oswald Spengler and Francis Parker Yockey, who speculated that a post-Marxist Russia would be a valuable ally in the global struggle against Anglo-American hegemony. Yockey, a fascist agitator whose work enjoyed cult status on the far right, in particular saw Russia as being instinctively anti-Semitic—a natural ally in the war against egalitarianism and liberalism.

After the end of the Cold War in 1991, the theories of Spengler and Yockey, which had once seemed so weird, took on a new plausibility. When Putin came to power in 1999, he started making an active effort to cultivate right-wing allies abroad through rhetoric emphasizing that Russia was a traditionalist nation committed to Christian values.

An adept fisher of men, Putin caught many a gullible guppy with this bait. In 2013, Pat Buchanan asked, “Is Vladimir Putin a paleoconservative? In the culture war for mankind’s future, is he one of us?” Buchanan made clear his answer: “As the decisive struggle in the second half of the 20th century was vertical, East vs. West, the 21st century struggle may be horizontal, with conservatives and traditionalists in every country arrayed against the militant secularism of a multicultural and transnational elite.”

In 2022, former Trump adviser Steve Bannon summed up the right-wing case in three succinct words: “Putin ain’t woke.”

Putin’s putative anti-wokeness still wins him some admirers on the hard right. Tucker Carlson, in particular, remains a fan of the argument that the West needs to make peace with Russia or risk losing global dominance to the real foe, China.

But the larger far right is not united around the Buchanan/Bannon/Carlson position. Newsmax, a network even further to the right than Fox, has taken to attacking Carlson as an alleged patsy of Putin. On Monday, Newsmax host Eric Bolling said, “Russian state media [is] using Tucker Carlson, alleged American, as propaganda to make their case that Russia is the victim.” The quarrel between Carlson and Bolling is an unedifying clash between competing types of xenophobia, hinging on the question of whether China is more dangerous than Russia.

In Europe as well, the far right is splintering over Russia. On September 23, Pew released fascinating polls showing that “Europeans who support right-wing populist parties have historically been more likely than other Europeans to express a positive view of Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin. While that is generally still the case today, favorable opinions of Russia and Putin have declined sharply among Europe’s populists following Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine.”

Particularly significant is the change in the right-wing parties that are in coalition with Giorgia Meloni’s FDI. As Pew reported, “The decline in favorable views of Russia and Putin has been especially pronounced among populists in Italy, which will hold an election on Sept. 25 to determine if the far-right Brothers of Italy party—backed by two other right-wing populist parties, Lega and Forza Italia—will lead the winning coalition. Favorable opinions of Russia have declined by 49 percentage points among supporters of Lega and Forza Italia since 2020—the biggest decrease of any measured in the Center’s analysis.”

Meloni herself is part of this evolution. In the past, she made friendly gestures to Putin, congratulating the autocrat on his 2018 victory in an election widely seen as crooked.

The splintering of the far right on Russia policy is fraught with implications for the future. On the one hand, it opens the possibility for figures like Meloni to curry favor from centrist elites. Pledging allegiance to the NATO consensus is her path toward respectability. On the other hand, it might also provide opportunities to marginalize figures like Carlson and Bannon.

The best response would be to decouple pro-Russian or anti-Russian opinion from the question of authoritarianism. The problem with both Meloni and Carlson is that they are xenophobic authoritarians. Whether they support Russia is a secondary matter. If they want to imitate Putin domestically, it doesn’t matter where they stand on NATO.

Jeet HeerTwitterJeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation and host of the weekly Nation podcast, The Time of Monsters. He also pens the monthly column “Morbid Symptoms.” The author of In Love with Art: Francoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014), Heer has written for numerous publications, including The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, The American Prospect, The Guardian, The New Republic, and The Boston Globe.