The Occupied Will Also Write History

Palestinian filmmaker Mohammad Bakri was censored for daring to tell the story of occupation in Jenin, Jenin. Now, he is trying again with a new documentary.

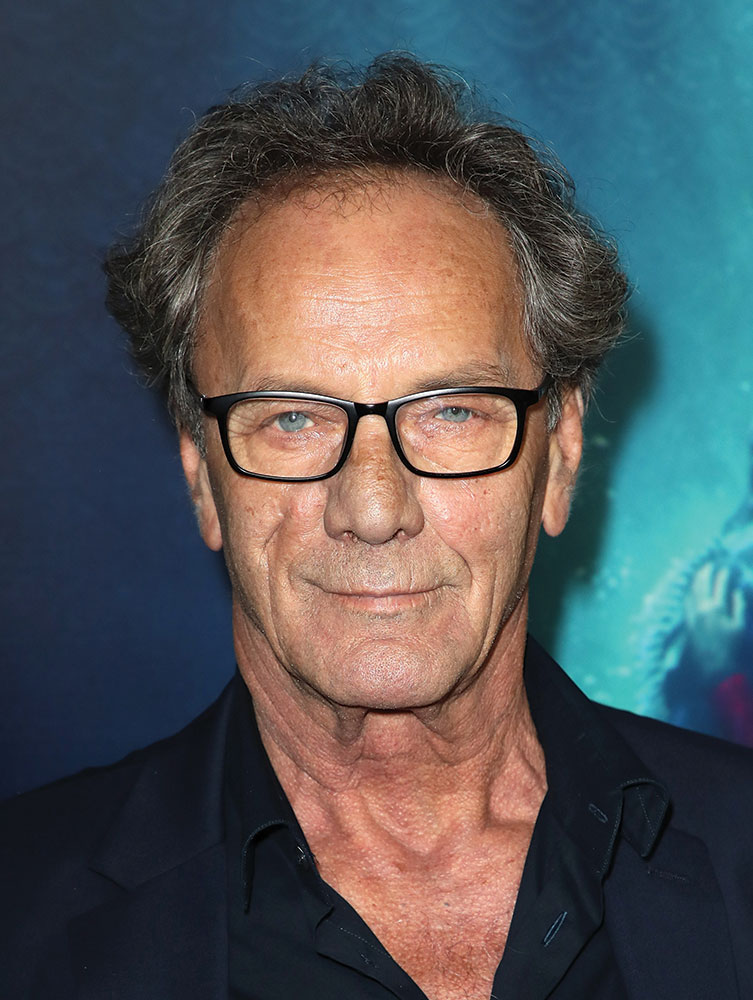

Amman, Jordan—The Palestinian actor and director Mohammad Bakri is singing the Israeli national anthem, his voice rising as he belts out a few lines in Hebrew. The 70-year-old is reminiscing about his primary-school days, which occasionally began with a rendition of the song. He remembered a speech that his principal made him deliver on Israel’s Independence Day to the Israeli officer who was overseeing martial law in his hometown of Al-Baneh in the Galilee. Like every Palestinian town that survived the Nakba, avoiding the fate of at least 530 villages that were destroyed and emptied of their residents, Al-Baneh was incorporated into Israel in 1948 and then placed under martial law until 1966 (Bakri was 13 years old when it ended). The speech, he recalled, “was about ‘We stand to remember what happened in the Second World War. We stand to remember what the Nazis did.’”

It wasn’t until he was a teenager that he understood the impact of that history—and the Israeli narrative—on his family. His illiterate father would repeat, on every occasion that he could, the story of what happened when Zionist military forces marched into his village on a sweltering day in 1948—about the men summarily executed, the relatives who fled into exile, and the imprisonment of every Palestinian male between the ages of 16 and 40, including Bakri’s father. That wasn’t part of the history that Bakri was taught at school. “We didn’t commit the Holocaust, but we paid the price for it. We could have lived together if they left Palestinians in their homes and lived alongside us. They would have been welcomed. But to live in our places—why? That is my story,” he told me. “They don’t want to hear it, because they don’t acknowledge me as a Palestinian. Israel wanted us to forget who we are.”

Bakri is what Israelis call an “Arab Israeli,” a term that many Palestinians (including Bakri) don’t use, because it erases their Palestinian identity within a generic Arab one while also splintering that identity, based on Palestinians’ fragmented geography, into Arab Israelis, Gazans, West Bankers, and East Jerusalemites. In the wider Middle East, Bakri is considered a “Palestinian of ’48” or a “Palestinian of the interior,” part of the quarter or so of the population of historical Palestine who were not expelled or forced to flee in 1948 and then forbidden from returning. There are now millions of Palestinian refugees in the diaspora. Although Bakri’s identification papers and passport are Israeli, he is emphatically Palestinian. “My Palestinian identity is in my heart, it is in my soul, it is not in my pocket,” he said. “It is not possible to be Palestinian and be folded into the Israeli story, because it means you have ceased to be Palestinian.”

We had decided to meet in Amman, the capital of Jordan, because it was neutral territory for both of us. Bakri, who still lives in his hometown, cannot travel to my base of Lebanon or most of the Arab world on his Israeli passport; Arab states forbid it. It is, however, possible for him to do so using an additional travel document issued by the Palestinian Authority, but not without facing serious legal consequences in Israel. As an Australian Lebanese New Zealander, I cannot cross an Israeli border to visit him, given Lebanon’s anti-normalization laws with Israel that carry charges of treason. These restrictions are one way that Palestinian citizens of Israel are disconnected from most of the Arab world.

We met to discuss Bakri’s new documentary, Janin Jenin; the first word of the title, janin, means “embryo” in Arabic, reflecting the idea that the Jenin refugee camp in the Israeli-occupied West Bank has birthed generations of resistance to Israel. Like a previous documentary, Jenin, Jenin, released 22 years ago, Bakri’s newest offering will also likely get him into trouble with Israeli authorities.

There’s a chill in the late-afternoon air, and Bakri, a father of six and grandfather to many, is urging me to put on a jacket. He’s sipping strong Turkish coffee and smoking incessantly, one e-cigarette after another, despite a ferocious cough. Still movie-star handsome, with shaggy gray hair and bright blue eyes, he is a man who says what he thinks and doesn’t take time to weigh his words. He’s done trying to explain himself to an Israeli audience that he believes is uninterested in narratives that start from a different premise and veer from its own.

It wasn’t always this way. A theater and Arabic literature graduate of Tel Aviv University, Bakri was a fixture of the Israeli theater and cinema scenes, performing in Hebrew and Arabic and winning awards—until he wasn’t. He is famous (or infamous) in Israel and the Arab world and has performed internationally. Five of his children have followed him into what has become the family acting and film business, with two of his sons, Saleh and Adam, starring in Oscar-nominated movies about life under Israeli occupation. Saleh, his eldest son, was once voted Israel’s sexiest man. His youngest, Mahmood, edited Janin Jenin and shared the filming with another of his sons, Ziad, who is also an actor and director.

Bakri pulls out another e-cigarette. We’re talking about the role of documentaries in the social media age, when atrocities are live-streamed and the deluge of debunked stories and confirmed facts can seem overwhelming to audiences. “If everything we are seeing on the Internet—on Facebook, WhatsApp, TikTok, and other sites—showing the destruction, the deaths of women and children in Gaza, hasn’t moved people to act, what will a film like mine do? I don’t expect it to do anything more than what we are witnessing now,” he said. “Look, there is a Palestinian saying that ‘God can’t hear the silent,’ so my stories are for God to hear. Maybe He will help us.”

Stories, and the controversies around them, have shaped Bakri’s life since childhood, but there is one story in particular that has defined him—and for which he paid a high price: his 54-minute documentary Jenin, Jenin. For 20 years, starting in 2002, Bakri was dragged through Israeli courts because of it, censored and censured, charged with defamation and fabrication, branded a traitor to the Israeli state and a terrorist sympathizer by members of the Knesset, and subjected to death threats and a grenade attack on his home.

The film presented the oral testimonies of Palestinian survivors of a 13-day Israeli military invasion of the Jenin refugee camp in 2002. Tensions and violence between Israelis and Palestinians had been rising since September 2000, when Ariel Sharon, then the leader of the Israeli opposition, accompanied by hundreds of heavily armed security forces, stormed Jerusalem’s Al Aqsa Mosque, triggering the Second Intifada. A Palestinian suicide bombing of an Israeli restaurant led to the assault on Jenin, part of what Israel called Operation Defensive Shield. At the time, it was the largest military offensive in the West Bank since the 1967 war.

The raid on Jenin left 52 Palestinians dead, of whom 22 were civilians, as well as 23 Israeli soldiers. Human Rights Watch documented Israeli war crimes committed during the operation, including the use of Palestinian civilians as human shields. Bakri made no claims in the documentary; there was no voice-of-God narration. He simply gave Jenin’s Palestinians the space to share their experiences, and in so doing challenged the Israeli narrative of a defensive surgical raid targeting “terrorists.”

“What is the fault of the child they killed? We are still pulling martyrs out from under the rubble,” an elderly man leaning on a walking stick says in the beginning of the film. “They say an investigating commission is on its way. Why do all the world’s regulations apply to us but not to the Israelis?” He gestures toward the sky: “Where are you, God?” In another scene, a hospital employee in a white lab coat recounts how the facility was struck at 3 am by 11 Israeli tank shells, destroying major infrastructure, including the hospital’s west wing. He spoke of warplanes unleashing barrages of missiles every few minutes. “I contacted the Red Cross, who contacted the Israelis, but to no avail,” he says.

There were angry protests outside the film’s premiere at the Jerusalem Cinematheque and at the few screenings of Jenin, Jenin that followed before it was banned by the Israel Film Council. The council called it a “propaganda film” capable of offending “the feelings of the public which may mistakenly think that IDF soldiers regularly and systematically commit war crimes, and this is completely at odds with the truth and the facts uncovered by investigations of the IDF and international bodies.”

In 2003, Israel’s Supreme Court reversed the ban, saying it infringed on Bakri’s freedom of expression. But in 2007, Bakri was once again brought to court after five Israeli soldiers filed a defamation lawsuit. That suit was dismissed, because the soldiers weren’t identifiable in the footage. Another soldier who appeared onscreen for a few seconds could be identified, however, and in 2016, with the support of the military’s top brass, he filed his own defamation suit. In 2021, a district court found Bakri guilty of defamation and ordered that every copy of Jenin, Jenin be confiscated. (It is still freely available on the Internet.)

After one final appeal, Bakri lost in Israel’s Supreme Court in 2022 and was ordered to pay about $55,000 for defaming the Israeli soldier, as well as $15,000 in legal fees. He is still paying the sum in installments. The court said that Jenin, Jenin portrayed “a fabricated narrative under the pretense of a documentary” and banned the film permanently.

Despite being censured for his work, Bakri returned to the Jenin refugee camp in 2023, days after the end of another major Israeli military incursion, to shoot Janin Jenin, which presents the oral testimonies of survivors, including some featured two decades earlier in Jenin, Jenin. Bakri doesn’t care about the possible consequences. “I am not afraid of them,” he told me. “There is strength in telling the truth. I believe in our narratives, and I believe that the occupied also write history.”

The telling of history has always been political, an enterprise shaped not only by whose stories get included and how they are framed but by whose stories are left out. There are voices heard, and voices silenced. History is about facts, but also, and more important, it is about power—as exercised through the erasure or the acknowledgment of those facts, as well as attempts to reclaim that power through alternative tellings.

Bakri’s experience with Jenin, Jenin is entangled in these tensions. His tribulations are rooted not only in questions of censorship and free speech, or activism and objective documentation. They are part of a deeper historical discourse about Palestine—or the lack of one. The “question of Palestine,” as the late Palestinian American professor and public intellectual Edward Said wrote in his 1979 book by that title, is “the contest between an affirmation and a denial,” one premised on what Said called Israel’s “refusal to admit, and the consequent denial of, the existence of Palestinian Arabs who are there not simply as an inconvenient nuisance, but as a population with an indissoluble bond with the land.”

The battle over what has happened in Gaza since October 7, 2023—and why it has happened—is already fierce and will likely only grow more intense once the dust of thousands of pulverized buildings eventually settles across Gaza, the fate of the Israeli hostages is determined, and the extent of Palestinian deaths, displacement, and injuries is fully accounted for.

Bakri’s two-decade-long ordeal portends what may happen to other documentarians who step outside the mainstream and tell another story. If he was persecuted for a film about a raid that left some 50 Palestinians dead, what might happen to those who chronicle a war that has left more than 38,000 dead? Israel has already shut down Al Jazeera’s operations in the country, claiming its news broadcasts are a security threat. “Today, I am convinced that our conflict with Israel is not a religious conflict or even about land—it is a war of narratives,” Bakri told me, one that he says started with Israel’s foundational narrative: “The Zionist movement said that they were a people without a land arriving to a land without a people. But we were here.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Since October 7, Israel has intensified its crackdown on both Palestinian citizens of Israel (who constitute about one-fifth of the population) and Jewish Israelis who engage in anti-Zionist speech or who oppose Israel’s offensive in Gaza. Although the policing predates Hamas’s surprise attack, the space for alternative views has been shrinking in Israel—and the penalties for tiptoeing outside that space have been growing.

Adalah, a nonprofit legal center for Palestinian rights in Israel, has documented hundreds of cases in recent months of students being expelled or suspended from academic institutions and of people being arrested or losing their jobs over social media posts. One incident, however, is considered unprecedented: the case of Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, a renowned Palestinian academic at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Shalhoub-Kevorkian is a feminist legal scholar whose research focuses on trauma, genocide, state crimes, gender violence, and surveillance. On April 18, she was arrested for comments she made on a podcast earlier this year and for academic articles she has written in the past. She was suspected of “serious incitement against the State of Israel by making statements against Zionism and even claiming that Israel is committing genocide in the Gaza Strip,” according to the court transcript. Among other things, Adalah has said, she was questioned about the terms she used in her peer-reviewed work, including “ontology,” “sacralization,” and “settler colonialism”; why she describes East Jerusalem as “occupied”; her research into the withholding of the bodies of dead Palestinians; and the meaning of the title of one of her books, Security Theology, Surveillance and the Politics of Fear, which examines Palestinian experiences of life and death within the context of the Israeli security state.

“This is the first time that an academic was arrested and investigated about articles that he or she wrote and were published by academic journals,” Hassan Jabareen, one of her lawyers and the director of Adalah, told me over the phone. “Legally, it is not allowed.”

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, who is in her 60s, was released on bail, but her case is not closed. Since her arrest, the effort to police speech in universities has only increased. In early June, the National Union for Israeli Students, which represents more than 350,000 students in some 60 higher education institutions, pushed for the adoption of a draft law to fire university lecturers who criticize Israel and its policies, a bill that is facing pushback from some universities.

Jabareen described Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s arrest and her harsh treatment in detention, which included being strip-searched, shackled, denied her medication, and verbally abused, as “racism based on humiliation.” Although Palestinian citizens of Israel can vote and there are several who sit in the Knesset, they are still second-class citizens, Jabareen said, because of the nearly 70 laws that discriminate against non-Jews. These include the 2018 “nation-state law,” which affirms that “the right to exercise national self-determination” in Israel is “unique to the Jewish people,” and which enshrines Hebrew as the country’s official language (downgrading Arabic) and “Jewish settlement as a national value,” without saying where those outposts might be. (Settlements on occupied land are illegal under international law.) Now a new proposed law would extend the practice of “administrative detention,” under which Palestinians in the occupied territories can be held indefinitely without charge or trial, to Palestinian citizens of Israel—but not to Jewish Israelis.

The impact of the suppression of free speech and dissent has reverberated beyond Israel’s borders. In mid-March, in a landmark decision in the United Kingdom, a 24-year-old Palestinian citizen of Israel identified by the pseudonym Hasan was granted asylum after claiming that “Israel maintains an apartheid system of domination of its Jewish citizens over its Palestinian citizens, whom it systematically oppresses.” Hasan, his legal team said, had “provided evidence to the tribunal that he is at enhanced risk of persecution [in Israel] because of his Palestinian solidarity activism in the UK and his anti-Zionist political opinions.”

The young man, who has lived in the UK for most of his life but is not a citizen, applied for asylum in 2019. In October 2022, Britain’s Home Office rejected his claim, denying that Israel persecutes its own citizens. This March, however, it abruptly reversed its position less than a day before Hasan’s legal team was due to challenge it.

Franck Magennis, one of Hasan’s lawyers, told me that he believes the war in Gaza influenced the Home Office’s ruling. “I don’t think that they would have withdrawn the decision in the way that they did if they hadn’t been much more worried post–October 7 that a judge would have said, ‘Yeah, I agree it’s apartheid. I also agree that it’s genocide, and I’m granting your client asylum on the basis that Israel persecutes its own citizens if they are Palestinian, anti-Zionist, or Muslim,’” Magennis told me over the phone from London. “I am not aware of any other Palestinian citizen of Israel successfully claiming asylum or even really attempting to.”

The irony, as Magennis pointed out, is that millions of Palestinians want to move in the other direction—back to Israel/Palestine—under the terms of United Nations Resolution 194, which stipulates that Palestinians have a right of return but has not been implemented since it was instituted in 1948. “In that context, it is very painful to suggest that Palestinians might not be able to return because they will be persecuted,” Magennis said. “But that’s the reality.”

Jabareen told me that the idea that Israel is the only democracy in the Middle East “has become passé.” Israel, he continued, “could be the only ethnic democratic state in the world—meaning Jewish democracy, as South Africa’s democracy was white democracy and America’s was for white Americans during segregation and slavery.”

Jabareen fears that the crackdown on rights and free speech will only get worse. “I hope that after the end of the war,” he said, “I won’t have the feeling of a Jewish person walking in Berlin’s streets in 1945 when I walk in Haifa, in Tel Aviv, and in Jerusalem.”

Bakri’s new hour-long documentary premiered in May to a packed house at Ramallah’s cultural center in the West Bank. The Israeli raid at the center of Janin Jenin is merely “a drop in a sea of what is happening in Gaza,” Bakri wrote on Facebook after the screening. “What will the Zionists say this time? Did I lie too? They need to look at Gaza and check themselves in the mirror.”

The new film begins with footage from Jenin, Jenin, reacquainting viewers with some of the more memorable characters. There’s the deaf man who took Bakri on a tour of the camp, signing what happened and acting out where and how people were killed; his son became a militant. There’s the preteen girl with a bob cut and bangs seen walking over the rubble, her eyes and words belying her age: “This land is like our son, our mother, everything we have,” she said in 2002. “There are still women. We will bear children and men who are stronger than those who were lost.” Today, she is a mother of four.

There are new characters too, including a woman who knows that the Israeli helicopters traumatizing her 5-year-old grandson are American-made Apaches—“He’s not normal, he’s not normal at all” after the raid, she says—and a 38-year-old actor at the Freedom Theatre, a landmark cultural and community center founded by Jewish Israelis and Palestinians, who identifies the bulldozers tearing up his streets in 2023 as the IDF’s Caterpillar D9s, an armored model he said he hadn’t seen in Jenin since 2002. (The D9s have returned to Jenin numerous times since October 7, most recently in June.)

“I consider myself the result of 2002, and I am living another incursion,” the actor tells the camera. “OK, I understand we are occupied, there are raids and resistance, and then what? My question is, where are we headed? There are generations that are living the same experiences.”

That’s the inescapable message of Bakri’s new film: that the Palestinian children of today are reliving and repeating the same stories, experiences, and traumas as the children of yesterday. One wonders what the children of Gaza will say, if they survive to tell their stories.

Although Bakri’s first Jenin documentary was primarily for an Israeli audience, he doesn’t intend to show his new film in Israel—“not out of fear of them, but because of a lack of hope in them,” he said. “I thought in my ignorance, such as it was 22 years ago, that because Jenin, Jenin was about the testimonies of real people, that it would change Israeli sentiment, and that was a big mistake.”

Israeli sentiment appears to have hardened since then. A Pew Research Center survey published in September 2023 showed that only 35 percent of Israelis believe that peaceful coexistence with Palestinians is possible, down 15 points since 2013. Polls conducted since October 7 have shown wide support for Israel’s war in Gaza. In January, 66 percent of Jewish Israelis polled by the Israel Democracy Institute said they did not want Israel to stop “the heavy bombing of densely populated areas.” While there have been protests calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and demanding that the government agree to a deal to free Israeli hostages and end the war, the latest Pew poll, published on May 30, indicated that a combined 73 percent of Israelis believe that their military’s response in Gaza was either about right or had not gone far enough.

“That’s why I make films,” Bakri said. “I want to explain for history’s sake the crimes that they committed and continue to commit against my people. They said Jenin, Jenin is full of lies. [With Janin Jenin,] I am showing them, ‘Look, history is repeating itself.’ How can it be a lie when the same stories, the same things, are happening again? The same people who were children then are adults now saying the same things, living through the same experiences. How is it lies?”

He continued: “I, the occupied, am obliged to tell my story in response to the stories of this occupation.”

Bakri made his new documentary, he told me, “for history’s sake, not for the [Israelis’], because throughout my life, I read history that they wrote. And we were not in it.”