Refaat Alareer Was My Friend. I Will Miss Him Forever.

The weight of his absence presses on me daily, a relentless reminder of the void he left behind.

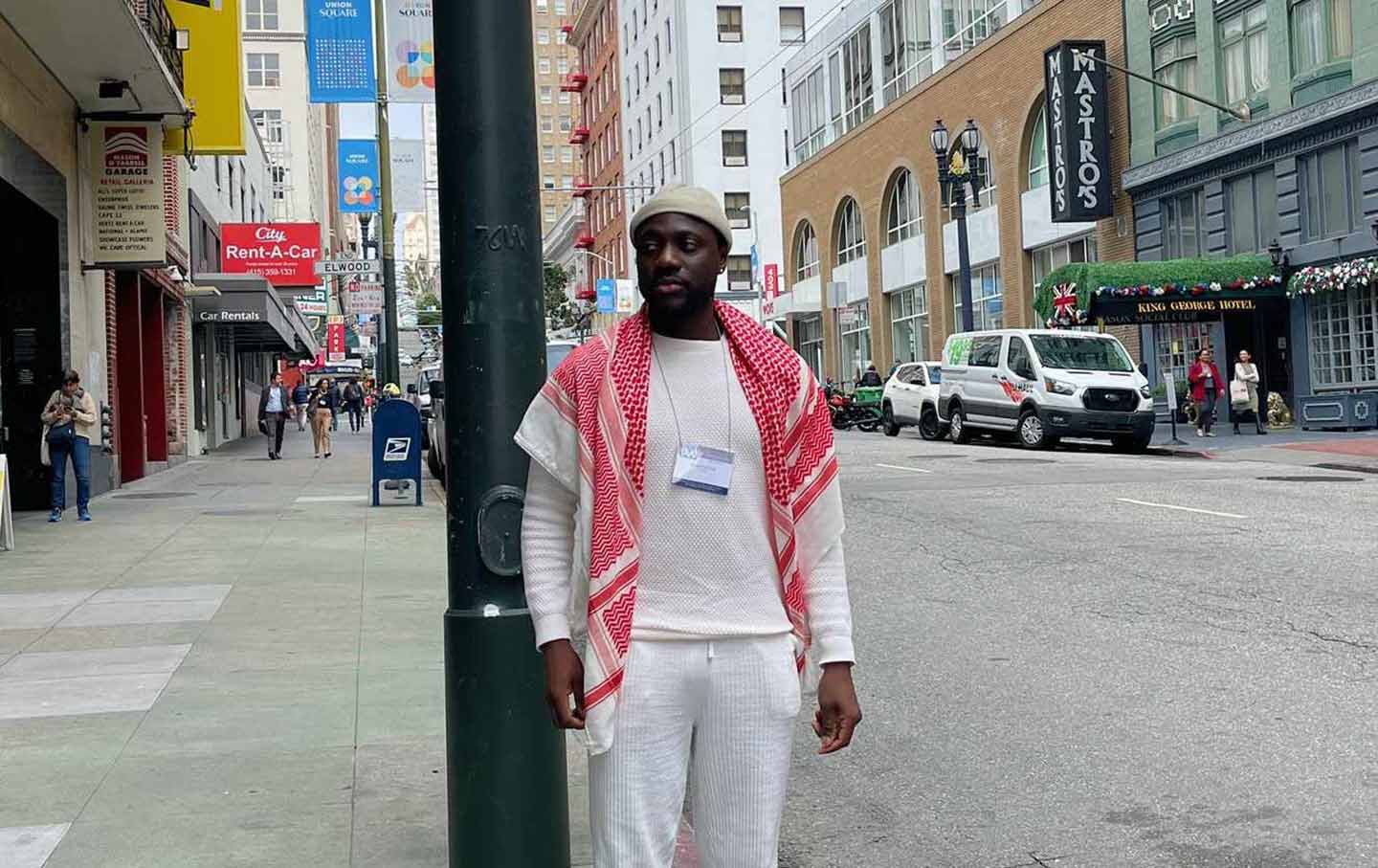

Mohammed Mhawish and Refaat Alareer.

(Courtesy of Mohammed Mhawish)Ten months after Israel killed Refaat Alareer, I still can’t bring myself to write about him in the past tense. The weight of his absence presses on me daily, a relentless reminder of the void he left behind. His name still feels too alive, too present, for the language of grief.

But beyond my grief, one truth stands clear: Refaat wasn’t—isn’t—just an iconic figure to our people, an artist, and a national voice—to me, he was all that and so much more. From the moment I met him as a wide-eyed freshman in college, he took me under his wing, shaping not just my career, but my entire life. His influence was woven into every story I wrote, every path I chose.

I know that I am joining countless others who have attempted to capture the essence of who Refaat was: a writer, a father, a brother, a teacher, a poet, a colleague. Some may have written about his gift with words, his talent as a storyteller, and his brilliance in the classroom. Others have shared how he carried the burdens of his people with dignity, never letting the fight for freedom dim his tenderness or his humanity.

I remember him as all of these things. He was my brother. He was my teacher. He was my mentor. He was my colleague. And he was my friend.

I have so, so many memories of Refaat. But the one I keep lingering on is from the last time I saw him. I had just come back to Gaza from abroad, and we met up for coffee. The date: October 6, 2023.

Had I known that cup of coffee would be our last, that the joy of his presence would soon turn into a cold, unfillable absence, I would have held onto that moment longer. We spoke about everything and nothing at all, the way you do with people you love.

The conversation drifted from Gaza’s delicious fish to the struggles of academia and writing under siege. Refaat was always a safe harbor for my worries about words—the way they wouldn’t always cooperate, or how they sometimes carried more weight than we were prepared to handle during times of terror and war. That day, he reassured me as he always did: “The words will come, Mohammed. You just have to trust yourself.” It was a simple statement, but one that always felt like a balm to my anxieties.

When we said goodbye that evening, there was no grand farewell, no sense of finality. I left that meeting feeling hopeful, as if the act of sharing coffee and words with Refaat made the world’s chaos just a little more bearable. He always had that effect.

For those who knew him well, praise from Refaat was rare—almost elusive. His approval wasn’t easily won and his standards were exceptionally high—but when approval came, it was worth more than any lengthy critique.

After an Israeli offensive on Gaza in 2022, I wrote an article for The Nation that garnered a lot of attention. As soon as the piece went live, Refaat texted me, thanking me for the “daring account” I had shared. “The story is making thunder out there,” he wrote, his words electric in their precision. “I am proud of you.”

I remember him texting me “Mumtaz”—meaning “excellent”—and “Batal”—which means “hero.” Those words, as simple as they were, felt both like an honor and a challenge to me—to push myself further so I could receive even better words next time. When I confided in him about the attacks I received in response to the piece, he didn’t hesitate. “When you’re on the minds of bad people,” he said, “that’s when you know you’ve done quite enough for the good ones.”

I found solace in his advice about conquering the fear of writing and overcoming any lack of courage in my decision to keep telling our stories. He would always say, “Palestine is always one story away, one stone away.” One time as I asked him about the resemblance in his word choice, he explained that stones symbolize tangible resistance against the cruel enemy. He said that “Palestine is not a distant concept but a living, breathing reality that is constantly shaped and reshaped by the stories and actions of us, its people.”

He would always say, “Palestine is always one story away, one stone away.” He explained that stones symbolize tangible resistance against the cruel enemy. He said that Palestine is not a distant concept but “a living, breathing reality that is constantly shaped and reshaped by the stories and actions of us, its people.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Even in his absence now, I find myself still clinging to his voice, his words echoing in my mind—“There will come a day when words need us, not the opposite, Mohammed.” But, since we lost Refaat, they have come with a weight, a gravity that I never anticipated. And though I wish I could share them with him, I know that somewhere, he’s still listening.

Refaat taught me that our struggle for liberation and the imperative need for writing do not only arise in times when “Free Palestine” is trending. Instead, there is a Palestine that dwells inside all of us, a Palestine that “needs to be rescued,” as he once said. He believed and lived to say that a free Palestine must indeed exist, where all people, regardless of color, religion, or ethnicity, live in freedom and justice.

In a 2014 article following Israel’s bombing of his university, Refaat wrote, “There are no poems of mass destruction.” At the time, I didn’t know much about him, but through that piece, I saw the mark of a fine and inspiring writer and a beloved academic—someone who would give his life in service to his people and homeland. As the years went by, I came to know Refaat personally and realized he was all that and more.

He would reflect the enduring presence of Palestine in both the physical and metaphorical sense. Every story told about Palestine, every stone picked up in resistance, keeps the spirit of the Palestinian struggle alive, he murmured to me as we spoke on the phone one day during the war. I could sense his voice had been shaken by exhaustion of displacement and lack of life necessities in Gaza then.

Refaat made me fall in love with the English language and literature. Even as a student, he stood apart, distinctly different. He earned his bachelor’s degree at the Islamic University in Gaza, and less than a decade later, returned as a prominent professor and deputy chairman of the English Department in the Faculty of Arts.

Since the moment I began studying Refaat’s poetic works, both as a student and later on as a writer, I have learned that the interconnection between literature and his voice has always been like two sides of the same coin; through literature, he spoke for his home, for his people’s freedom and political liberty. His words became a source of hope and defiance against life under the unjust military rule. Throughout his literary syllabus on campus, he demonstrated the profound impact of art in the struggle for justice in the case of Palestine.

I am unequivocal in my belief that Refaat was—and will continue to be—one of the finest poets and storytellers Palestine ever produced. He believed that poems are tools of creation, of rebelling against power and destruction, and of illuminating the shared humanity in every reader.

On May 19, 2022, Refaat and I were enjoying a cup of coffee and a basket of Gaza-grown strawberries on the Gaza Sea coast. Usually, every time we met, we would bring fruits, books, and a lot of laughter and funny stories about friends and other colleagues. We had planned to meet after a long day and busy schedules, this time over lunch at a small café, tucked away from the noise of campus and city downtown.

The conversation, as always, started casually—news, family, the usual catching up. But then, in that unassuming way of his, he leaned in and said, “What if we wrote a book together—something non-fiction from Gaza, about Gaza?

I paused, unsure if I had heard correctly: Refaat Alareer just asked me to write a book with him!

At that moment, I didn’t feel like I was sitting with my former professor but with a friend who didn’t mind—and enjoyed—mocking his own haircut and sharing stories about his mischievous childhood as a schoolboy.

“A book?”

Sensing my fear that I might not be fully able to bring such an idea into action, “Yes,” he smiled, a glimmer of excitement in his eyes. “Not just any book. A book for them—young writers, the youth of Gaza. Something that speaks to their struggles, their hopes, and the world they’re trying to create, even under occupation.”

The idea seemed as daring as it was beautiful. He suggested we compile voices—Palestinian writers, artists, creatives—each sharing stories that offered a glimpse into what it meant to exist, to create, and resist in this place. He wanted it to be a testament to the resilience of our people.

We talked about it for hours, mapping out ideas between sips of coffee. I vividly remember his passion as we discussed it. How we could guide young writers, show them that their voices mattered, that their stories had the power to transcend the blockade around us. We imagined contributions from some of our favorite writers, poets, and local artists, mixing the written word with visuals, poems, maybe even music. A mosaic of Gaza’s persistence.

On that day, Refaat told me that “Knowledge is Israel’s worst enemy, and awareness is Israel’s most hated and feared foe.” As he explained what he meant, it became clear to me that everyone has to believe in the transformative power of knowledge and awareness in the context of confronting the Israeli erasure of the physical and ideological existence of Palestine.

He said that knowledge equips us with the tools to understand the historical and contemporary realities of the occupation that is “shipping away our lands and rights,” while awareness fosters a “collective consciousness that challenges injustice and oppression.”

Fully and firmly, Refaat hated ignorance. For him, “Ignorance is the ally of tyranny.” He always fought through his intellect to have as many young minds informed as possible, as that is actually “the greatest threat to the occupation state.” He advocated for the importance of media literacy and critical thinking in the fight against misinformation and propaganda, and demanded his students and trainees always seek the truth and write with awareness as a form of resistance as they write.

As we left the café, I remember him saying, almost in passing, “We owe them this. We owe it to those who need to know their voices matter, to their people, to their land, no matter how small they think they are. We owe it to our homeland. We owe it to Gaza.”

At that moment, I didn’t know that our plans would be interrupted by the brutality of war, that we wouldn’t get the chance to sit together again and flesh it out. But the vision remains. And now, more than ever, I feel the weight of that promise we made—to carry forward the stories of our people, as he always did, courageously and with hope, even in the darkest of times.

Refaat’s reassuring spirit and the plan we madestill linger in my mind.

Since the start of the ongoing war, Refaat turned to social media and his writing to document the daily struggles for survival that he and his family faced, as Israel deprived the enclave of basic necessities—water, electricity, food. He chronicled the brutality his people endured with unwavering bravery and eloquence. His words captured global attention, drawing digital support and solidarity from around the world.

He would text me regularly, sometimes along with our network of writing peers, urging us to keep telling our stories to the world, undefeated by fear or reluctance.

Shortly after October 7, I was asked to write a story explaining the situation in Gaza during Israel’s war. Struggling to convey the human toll at the time, I immediately turned to Refaat for advice.

“Just write from your heart, and share a draft with me when you’re done,” he texted me back. “Try to make it more human and less political,” he said. “It’s not time for political commentary, but for the world to know what’s basically happening.”

The last time I spoke to him was days before his death. We talked about our latest work, shared updates about life in the midst of war—just as we often did back then. But something he said that day struck me more deeply than anything else: “While our cause is worth dying for, it’s our insistence on living that bothers our enemies the most. Don’t forget that, Mohammed,” he said.

I haven’t. And I won’t.

When Refaat wrote his final, powerful poem, “If I must die, you must live to tell my story,” I felt an overwhelming sense of duty, as if he were speaking directly to me—and to all of us, his friends and students in Gaza. It’s as though he left us with a profound responsibility: to continue the fight for freedom by telling the stories of those who first braved it, those who dedicated their lives to it and were killed for it. They passed the torch, and now it’s our turn to pick up the pen and carry their legacy forward.

At a time when the international community’s complicity was at its peak, Refaat dared to write and speak. And he was killed for it. The fact that he was murdered simply because he spoke out and demanded to live in dignity and freedom does not make him guilty, as Israel propagated, but a hero. He wanted to live to see his first grandchild, to grow old among his grandchildren, to tell them stories in his own way, and to become their first storyteller.

Even with the constant threat to his life, Refaat remained unwavering in his demands during our writing classes. He insisted on personal journalism—storytelling that challenged systematic injustice and held the powerful accountable. And amid the choking reality of death and war, Refaat’s loss forces us to confront both the unbearable heartbreak and the relentless determination to keep telling the truth that Israel has tried to silence at all costs.

According to family testimonies, Refaat received a threatening phone call from the Israeli military one day before he was killed. Fearing for his safety and that of those around him, he decided to take refuge in his sister’s apartment in Gaza City’s Tal Al Hawa neighborhood, believing it would be “safer.” He didn’t want his targeting to endanger the many civilians around him.

I’ll never forget the day I received the news of Refaat’s killing. It was as if someone tightened a rope around my neck and choked the breath out of me. His death, on December 8, 2023, came just a day after my own home was targeted while my family and I were inside. The shock of losing him only aggravated the physical pain and psychological trauma I was already struggling to endure.

I remember crying hysterically that day, and even now, every time I think of him or see him in my dreams, the tears come back. Whenever I see his name, his picture, or someone holding one of his poems high, I find myself wishing he hadn’t died—that he had lived long enough for all the stories we still had left to share.

The pain of knowing there will be no more calls for writing advice, no more shared stories of Gaza’s diverse food stalls, no more reading about our life struggles in the besieged city, is a sorrow I can scarcely bear. I think of all the unspoken conversations we’ll never have, our book ideas that were cut short, the lessons he would have taught me, the knowledge he would have shared, the stories we would have told.

More than ever, we feel the need for Refaat’s voice now. Refaat hasn’t left behind the pain of his loss only but the hope and optimism that we can live a different life, under different circumstances.

The global intellectual community must rally to protect Palestinian academics and intellectuals. We must keep telling our stories, as Refaat always urged—speaking the truth, writing it. But how do we continue reporting under constant threat? How do we work through the fear, the constant targeting? We write through the stench of bodies torn apart and blanketing the city. Hundreds of journalists, academics, artists, and writers in Gaza mourn his absence, while many others have been killed trying to keep his spirit alive.

The personal conundrum I face barely captures the broader scale of Israel’s systematic targeting of brave minds in Palestine, like Refaat, whose legacy only grows louder and more powerful after their death. Yet, there is hope. Our voices are reaching further and resonating across the globe, as seen in student demonstrations and movements standing in solidarity with us.

Refaat’s words didn’t just stay with me after his death—they became an ache, carving their weight deeper into my heart with every passing day. Each memory of his voice now feels like both a gift and a wound, constantly reminding me of what I’d lost and what I still have to carry forward without him.

Oh, Refaat, today I am holding my head high and grieving you with tears of honor. I pray you’ve found the eternal peace you deserve. Knowing you wasn’t just a privilege—it was a joy, a relief, a responsibility, and a lifelong duty. Your wisdom and kindness left an indelible mark on my life. As I once promised you, I will always make you proud. I will carry your spirit and legacy forward in everything I do and keep your voice alive in every word I write.