Gaza Shows the Difference Between International Law and the “Rules-Based International Order”

Adherence to US hegemony determines who does—and does not—get to violate the architecture restraining state violence.

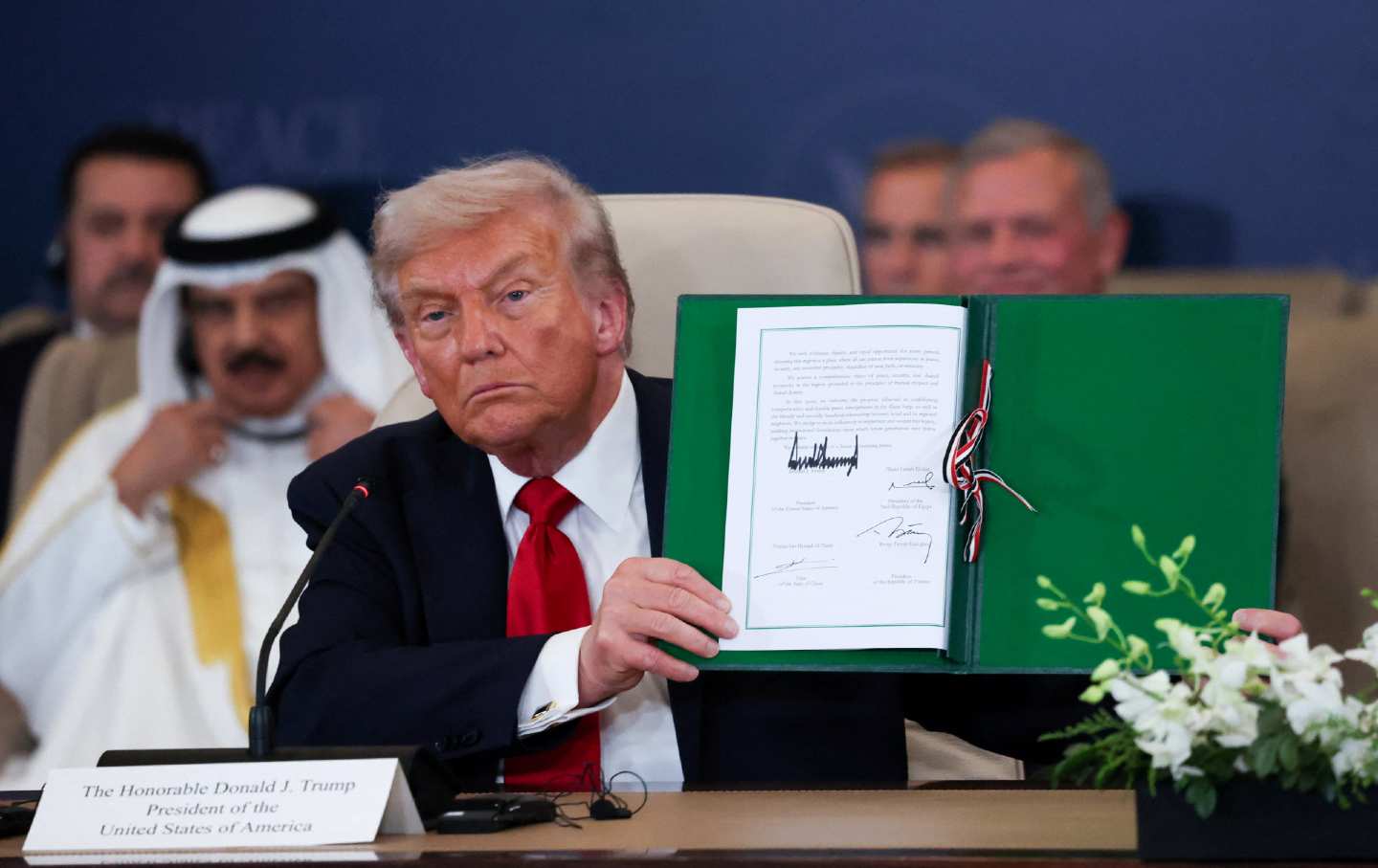

The Biden administration invokes the “rules-based international order” to allow Israeli government to engage in acts it condemns when Russia does them.

(Ariel Schalit / AP)As the Palestinian death toll crossed the 10,000 mark in early November, two anonymous mid-level US diplomats marginalized by President Joe Biden’s support of Israel warned that the US urgently needed to “publicly criticize Israel’s violations of international norms such as failure to limit offensive operations to legitimate military targets.” Israel’s war in Gaza, they wrote in a memo leaked to Politico, was sowing “doubt in the rules-based international order that we have long championed.”

The diplomats are part of a growing chorus against the impunity that the United States has long provided Israel for unambiguous violations of international law. Jordan’s King Abdullah II railed that “in another conflict”—Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—the US condemned “attacking civilian infrastructure and deliberately starving an entire population of food, water, electricity, and basic necessities.” International law, he continued, “loses all value if it is implemented selectively.”

Abdullah is not the only one taken by the similarities between Ukraine and Gaza. On a Zoom briefing arranged by the writer Peter Beinart a week into the conflict, former Knesset speaker Avrum Burg said the Israel Defense Forces’ approach—flattening infrastructure with air strikes and artillery to make urban warfare easier for tanks and infantry—amounted to a “Russian military strategy.”

More on the Israel-Gaza War

The diplomats are right: Biden’s green light to Israel creates doubt in the legitimacy of the “rules-based international order.” It also clarifies what that order truly is. For while the rules-based international order sounds like “international law,” in reality it is the substitution of international law with the prerogatives of American hegemony. Biden is not engaging in hypocrisy, exactly, in punishing Russia for acts that he materially supports when Israel does them. He is engaging in exceptionalism.

To be clear, many in and out of the US government often treat the term “rules-based international order” as a synonym for international law. And proponents of the rules-based international order are happy to use or hail international law when it serves the United States, like when the International Criminal Court seeks to arrest Vladimir Putin for his war crimes in Ukraine. Yet the United States will never submit itself to the ICC. Under President George W. Bush, the US revoked its (unratified) signature to the treaty establishing the court. Under President Donald Trump, it sanctioned the families of ICC prosecutors who opened a war-crimes investigation into the US war in Afghanistan. That is how the rules-based international order operates. It doesn’t replace the mechanisms of international law; it places asterisks beside them. The rules may bind US adversaries, but the US and its clients can opt out.

A brief history of how the US spent its post–Cold War moment of supreme global power shows the rise of what we now call the RBIO at the expense of international law. When the United Nations wouldn’t authorize war on Serbia to save Kosovo, the United States acted as if NATO wielded the same imprimatur, and no nation was strong enough to challenge its assertion. That impulse was supercharged by 9/11. The 2003 US invasion of Iraq made a mockery of international law while claiming cynically to uphold it.

Though many in respectable circles objected to Bush’s flagrant aggression, a strain of liberal foreign policy argued that American power could save international law from itself. In 2006, the scholars Anne-Marie Slaughter and John Ikenberry proposed a grand strategy they called “a world of liberty under law.” They sought to reform and bolster existing international institutions. But if the UN “cannot be reformed,” they urged a “concert of democracies” to “provide an alternative forum for liberal democracies to authorize collective action.” In such fashion, the rules-based international order coalesced as a concept.

What began as a response to an emergency in the Balkans is now routine. President Barack Obama turned a UN humanitarian mission in Libya into supporting the overthrow of Moammar El-Gadhafi. After the wreckage of Iraq became the horror of ISIS, the US stationed troops in eastern Syria with neither UN mandate nor invitation from the unfortunately enduring Bashar Assad. Trump ordered the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, one of the most important figures in the Iranian government.

“The RBIO cannot replace international law—international law is inherent in the very concept of a state, of an international boundary, of treaties, of human rights,” Mary Ellen O’Connell, an international-law expert and professor at the University of Notre Dame, said via e-mail. “But the RBIO is undermining knowledge and respect for the system of international law. The law’s capacity to support solutions to global challenges from war and peace to climate change and poverty is being severely degraded by this competing, deeply flawed concept.”

Now consider what Israel is doing in Gaza. By early November, it was killing an estimated 180 children a day. The IDF demanded that Palestinians abandon their homes in northern Gaza and then, when hundreds of thousands complied, attacked the destinations in southern Gaza it herded them toward. After starving Gaza, denying it medicine, shutting off its communications, killing its journalists, besieging and even raiding its hospitals, and asserting that places of mass refuge are Hamas positions, Israel claimed to have killed “dozens” of Hamas commanders, out of a total death toll at the time of 10,500 Palestinians.

There is no way to square those figures with international law’s demands for distinction and proportionality. Israel, however, knows it has something stronger than international law: the protection of the rules-based international order.

Holocaust scholars like Raz Segal of Stockton University and Omer Bartov of Brown University consider Israel to be at or past the threshold of committing genocide, the most horrific of atrocities that a state calling itself Jewish could possibly commit. Biden was stunned in 2022 when much of the world—the parts that tend to be on the receiving end of American power—did not accept the US narrative of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That should have been a layup. Now the world is watching Israel annihilate Gaza with US weapons and diplomatic support. In doing so, Biden and Netanyahu show what the rules-based international order really is: not a world of liberty under law but a mass grave.