The Legacy of the British Legal System Continues to Inflict Misery in Sierra Leone

Decades after independence, colonial-era laws have created a mass-incarceration crisis in Sierra Leone as poor citizens are thrown into prison for the smallest offenses.

A few summers ago, I met a young man in a prison in the center of Sierra Leone. The man was thin and tall, with a gentle demeanor and shy smile. His clothes were worn and smelled of stale sweat, which wasn’t surprising given that the prison, with its tin roof, small cells, and open courtyard, was baking in the mid-afternoon sun. Leaning in close, his voice quiet, the man explained that he had been in prison for a year and a half, although he hadn’t been found guilty of anything yet. He’d been waiting all that time just to have his case heard before a judge.

The man was accused of not paying off a $50 debt. He had taken on this debt, he explained, to pay an $80 traffic ticket the police had given him for not having a rearview mirror on his motorbike taxi, which he rode for a living. What poor luck, he mused: He had wanted to avoid jail time for the traffic ticket, so he took on the debt, but the debt had landed him in prison anyway. After 18 months, he still had no notion of when he might leave.

I met the man while visiting the Makeni Correctional Center, a busy prison for men housed in a low, whitewashed building just off the main highway at the edge of a bustling city. He was one of scores of prisoners accused of petty crimes—things like loitering, being a “public nuisance,” and traffic infractions. On the day I visited, around 15 percent of those at the facility had been detained for debt. Eighty percent had not yet had a trial.

With so many prisoners locked up for petty offenses and so many awaiting trial, the prison was severely overcrowded. The square building consisted of about a dozen cells, which surrounded a courtyard about the size of a small classroom. As I made my way inside, I was warned by a guard that it would be hot. (“Do you have water?” he asked.) But the combination of the tight, unshaded courtyard, the corrugated zinc roof, and the tiny number of cells housing scores of people made the prison not just hot but unbearably so. There was one clinic, a few “recreational areas,” a single bathroom, and one tiny kitchen. (I jotted in my notebook: “Looks awful. Smells awful. Food looks like it’s rotting. Everything awful.”) When I conducted interviews later that day, one prisoner told me, “They pack you like they pack fish in tins.” Another complained that the soup they had for dinner was “like empty water.” While the prison officially had space for 80 people, 184 were incarcerated there when I visited. All told, the prison was at 230 percent capacity.

The warden, a tall, self-assured man with a big smile and a strong handshake, gave me an official tour. As we slogged through the heat, both of us visibly sweating, he offered details about the roof (newly replaced—a point of pride); the “art station” where men could decorate plastic water bottles with twine, thanks to donations from an international NGO; the TV programs that the inmates were allowed to watch. The warden was animated, but I had a hard time following his words. I was so focused on the overwhelming discomfort of the experience—the heat, smells, and sounds—and on the astonishing fact that hundreds of men lived inside this tiny space, many for the smallest of crimes, that I was barely able to form a question.

The warden then offhandedly mentioned that he was acquiring provisions—soap, rice—on loan from local shopkeepers. The prison hadn’t received money from the central government for over three months and was running out of even the most basic supplies. It had depleted its tuberculosis testing materials, and its supply of TB drugs was dwindling—both points of concern, since at least a dozen inmates were infected.

“You’re in debt?” I asked. The warden shrugged, offering a little smile. “You’re in debt, because you’re housing so many people who can’t pay back their debts?” He shrugged again.

“That’s how it goes,” he told me. “What can I do? I’m just following the law.”

The Makeni Correctional Center is not the most troubled prison in Sierra Leone. Nor is it the most crowded. It is but one of the many prisons in the country that are crammed with men, as well as women, who have been detained for petty crimes. In some prisons, space is so tight that cells just six feet by nine feet are used to house nine or more inmates. As of October 2023, Pademba Road Prison, Sierra Leone’s main prison, housed 2,097 people despite having a capacity of 342. And with only 48 judges serving the country’s 16 judicial districts, which together are home to more than 8 million people, the accused can wait months—sometimes years—for a trial.

To understand how it is that so many men and women came to be warehoused in the country’s prisons for petty crimes, we need to look back some 200 years, to the beginning of British colonial rule over Sierra Leone. In 1808, Britain claimed control of Freetown, the country’s capital, after which it expanded its reach into the provinces. As its name suggests, Freetown was initially construed as a humanitarian experiment, conceived by British abolitionists as a place where people emancipated from enslavement could start life anew. But it was also, fundamentally, a colonial project. Its aim: to see if these formerly enslaved people, as well as indigenous Sierra Leoneans, once exposed to British laws and mores, could be molded into “Black British” living out British norms and traditions thousands of miles from London. Toward this end, and as was the case in other British colonies, laws adopted in the UK were automatically incorporated into Sierra Leone’s legal system without serious consideration of the local context, history, or traditional practices.

One example is the 1916 Larceny Act. Passed in the British Parliament, the law outlined different types of theft: the stealing of dogs, cattle, land titles, trees, electricity, mail, mohair. It also included two provisions that, in effect, made a person criminally liable if they lied about how they intended to use a loan. Although this was meant to dissuade or punish obvious cases of deceit—say, a debtor claiming they would repay without ever actually planning to—in practice, the act gave extraordinary discretion to police officers and judges, who could determine that a debtor had “fraudulently converted” a loan when they didn’t pay it off, whether that was in fact because of intent or rather circumstance—say, falling behind on payments because of a health emergency.

As the act was replicated throughout the British Empire, debtors from Sierra Leone to India whom the police and the courts determined had intentionally not paid off their loans could wind up behind bars. Other colonial legal codes punished those who committed other small transgressions. The 1902 Lunacy Act made it possible for police to forcibly detain people with mental health issues and, under certain circumstances, seize their assets. Homosexuality was also punished with imprisonment, as was loitering, “absence from work,” disorderly conduct, using “insulting language,” being a “rogue and vagabond,” and other vague and broad actions of daily life. Louise Edwards, a South African lawyer who has studied the impact of the criminalization of petty offenses in Africa, says, “The purpose of these colonial-era laws was to segregate and punish, and to hold public spaces for colonial-era masters—a white cleansing of public spaces.”

When Sierra Leone gained independence from Britain in 1961, the transition did not include a dramatic change in the country’s laws. Today, except for laws passed after independence, much of Sierra Leone’s penal code remains a blueprint of the British colonial legal system—even as Britain itself has updated many of these laws (the Larceny Act, for example, was repealed in the UK in 1968). This is true in other former British colonies as well. From Uganda to Zimbabwe, South Africa to Ghana, laws criminalizing petty offenses largely remain in effect. In East Africa, where some prisons are at upwards of 200 percent capacity, 60 percent of the people awaiting trial in prison are incarcerated for petty offenses. In Nigeria, nearly three-quarters of prisoners awaiting trial have been charged with such offenses.

Today, these charges are disproportionately used against the visibly and very poor, a legacy of the “cleansing of public spaces” that Edwards describes. More practically, poor, marginalized people are the easiest to extort and the most likely to be dealing with things like intractable debt and “public disorder,” given that many facets of their lives unfold in heavily policed public spaces: They may sell food or trinkets on busy roadways or live in makeshift homes that provide little privacy. Their visibility makes them vulnerable to accusations of loitering when they hawk wares on a sidewalk or of disorderly conduct when a family spat spills onto the street. Some police officers wield colonial-era laws against petty offenses to brush “bad boys”—unemployed young men—out of public spaces or to extract an easy bribe from a woman trying to run an informal business.

Edwards and her colleagues see the use of these laws today as a means of criminalizing the “conduct of life-sustaining activities in public spaces.” Gassan Abess, a long-standing commissioner with Sierra Leone’s Human Rights Commission, says the laws “criminalize poverty.” In 2019, 90 percent of all petty-offense cases represented by two Sierra Leonean legal aid organizations, AdvocAid and the Center for Accountability and the Rule of Law, involved charges levied against unemployed or low-paid workers. In a 2018 submission to a United Nations working group on discrimination against women in the legal system, AdvocAid wrote that “the majority of female defendants [in Sierra Leone] are arrested for minor, petty crimes borne of poverty.”

The collision of poverty, archaic laws, and the creaking wheels of an overwhelmed bureaucracy were on display in the police stations, courtrooms, and jails I visited all over Sierra Leone. I spent weeks observing trials at the High Court in Kono, a district in the far eastern part of the country. Because there’s a shortage of judges, there isn’t a regularly sitting High Court judge in the area, which is mostly rural and sparsely populated. By the time the court convened, months had passed since a judge had heard a case. Many of the accused had been waiting behind bars “on remand,” meaning they had not yet had a full trial. A man accused of fraudulent conversion—of not paying off, or misusing, his debt—had been waiting for a full year; another, accused of “store breaking and larceny,” for nearly a year and a half; and another, charged with illicit mining, for 10 months and 28 days. One woman had been waiting for nine months for her court papers to arrive from a lower court, about 60 miles away. She couldn’t see a judge or be released until that happened. If the papers didn’t make it in time for this session—each province’s High Court sits just once every few months because there are so few judges—she’d have to wait for the next session, prolonging her pretrial incarceration by nearly half a year.

Despite the delay, those I spoke to were hopeful that having a hearing would finally offer some justice, or at least clarity about why exactly they were incarcerated and what they would have to do to be released. They had been told to wait; now a judge was here, and they expected results.

But the court was stunningly dysfunctional. Each hearing lasted about 15 minutes, regardless of whether this was a defendant’s first appearance before the dock or their sixth. Many had had repeat hearings because a witness hadn’t shown up or a file couldn’t be found, meaning they would have to wait several more months before seeing a judge again. The evidence that was offered was primarily given by the police, who functioned both as prosecutors, mounting cases against defendants, and as witnesses, offering testimony to back up their own evidence. The statements the police took when they made an arrest made up the bulk of the evidence in each case. These statements were written, and then read in court, in English, which is the country’s official language, even though only a 10th of a percent of Sierra Leoneans cite English as their first language, and less than 6 percent as their second. (Most people speak Krio, a language that has its origins in English and African languages. A small minority, around 5 percent, don’t cite Krio as their first, second, or third language.)

Language became a clear barrier when defendants were asked to comment on their initial statements—which, again, had been read in English, often by a police officer. Then, sometimes just a few minutes after that, defendants would be offered a guilty plea by being asked, in Krio this time, “Na so e be?” (which roughly translates to “Is this what happened?”). In my interviews with prisoners in Sierra Leone, several of those who were charged with petty crimes told me they answered “yes” to the question: “Yes, I took out the debt.” “Yes, I was unable to pay it back.” “Yes, I used the money to pay for my kid’s healthcare instead.” “Yes, this is what happened.” They did not mean “Yes, I never intended to pay back the debt” or “Yes, I intentionally committed fraud.” The judge overseeing the Kono High Court, Augustine Kailey Musa, told me it was in a defendant’s interest to plead guilty and “not waste the time of the court,” regardless of what had actually transpired. “If you want me to consider poverty and you plead guilty [first], then I would definitely temper justice with mercy. But if you plead ‘not guilty’ and then [later] give the issue of poverty, I won’t take lightly to it. I don’t really like people who waste the court’s time.”

Judge Musa had complete discretion over the sentencing, and his decisions had no apparent rationale. One young man was given a one-year prison sentence for a $60 debt. Another young man, who owed $700, was released and gently told to “slowly pay it off.”

A 28-year-old man I met back in Makeni, who had been waiting for a trial for two and a half years, put it this way: “There’s no justice for the poor. For those with money, they’ll listen to the case. But for those without money, we’re stuck here. All the plans that I had, they’re gone now.”

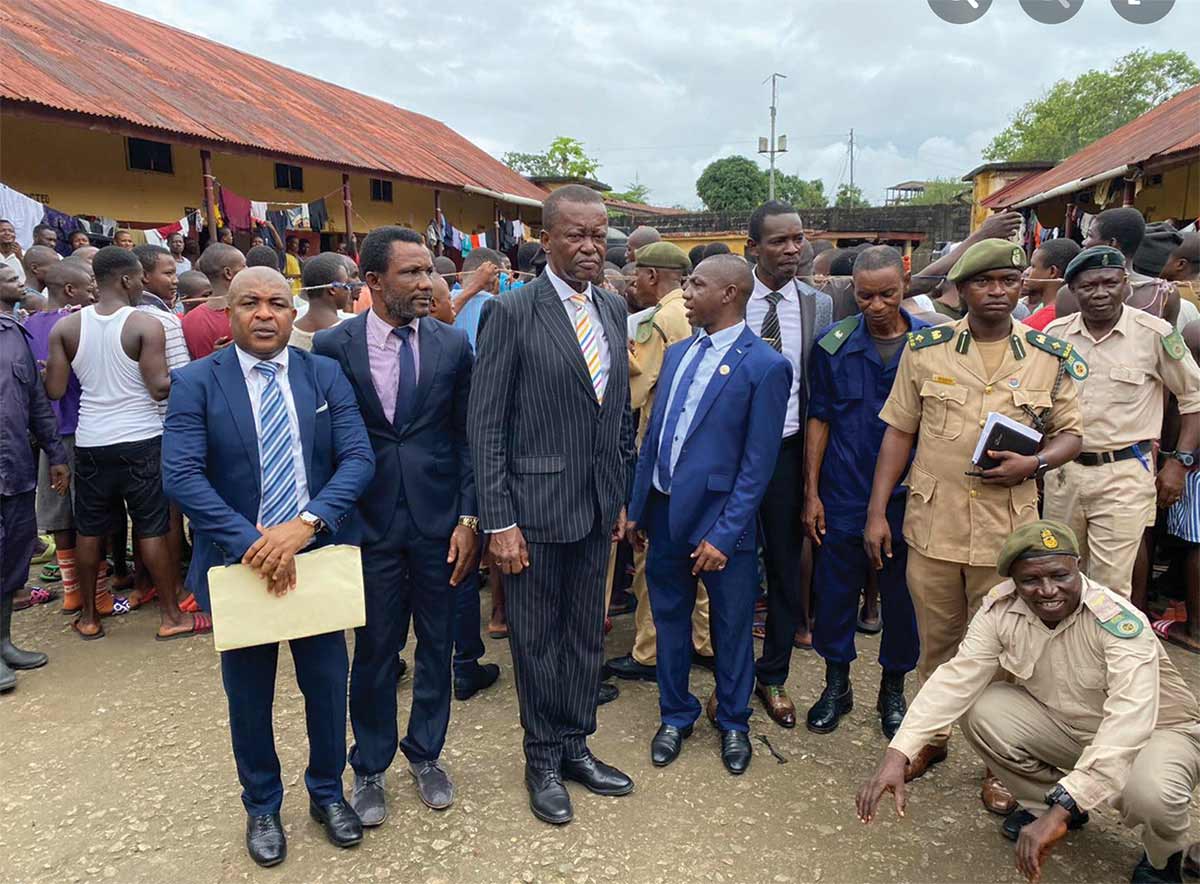

No way out: Men imprisoned at the Mafanta Prison peer out at the world. In 2016, Sierra Leone’s Human Rights Commission decried the squalor and lack of rehabilitative programs as “inhumane.”

(Saidu Bah / AFP via Getty Images)

It seems obvious, given the country’s overcrowded prisons, log-jammed courts, and remarkable absence of justice, that laws against petty offenses, which weren’t written for Sierra Leone in the first place, should be repealed. The dozens of lawyers, judges, and legal advocates I spoke to said as much. Doing so is possible through an act of Parliament, which can strike or amend legal codes. But given that British laws form the backbone of the country’s legal system, going through each and deciding what to keep, what to tweak, and what to cull demands time, resources, and an immense amount of political will—all of which are in short supply in a country that’s fractured by two warring political parties and that faces a host of issues, from deadly environmental disasters to deeply inadequate basic services to inflation that soared to over 52 percent in 2023. More practically, given that Sierra Leone has dozens of old colonial laws, it’s hard to know where to start. “These laws have been with us for centuries,” Acting Supreme Court Justice Nicholas Colin Browne-Marke told me. “It’s difficult to just throw them overboard.”

Yet even without a significant overhaul of the system, the laws could be enforced differently—or not at all. There’s no reason that archaic legal codes have to be applied today; doing so is a choice. All of the Sierra Leonean judges I spoke to noted that they felt the laws were used inappropriately by the police: Unpaid debt, family spats, and hawking wares in inconvenient spots should not be criminally prosecuted except in rare cases; the police could instead treat these as civil offenses. Even in more serious cases, bail could be granted or a small fee required in lieu of jail time. The problem, the judges suggested, is that as gatekeepers of the legal system, the police have discretion over whom to charge and with what. And they have an interest in charging people—or threatening to charge them—with criminalized petty offenses.

That interest is often financial. Gassan Abess, the human rights commissioner, pointed out that, given that the police are paid low wages—or sometimes not paid at all—bribes, extorted by threatening to wield petty-offense laws, are a convenient alternative source of income. Mariebob Kandeh, who heads an association of market women in Freetown, told me, “The police extort a lot of money from [debtors]. A woman tells them, ‘I don’t have the money to pay the debt,’ but they ask her to pay $5 to be let go. Where is she supposed to find this money?”

This is true not only in Sierra Leone but throughout much of the former British Empire—“along colonial lines,” as the South African lawyer Edwards put it—where colonial-era laws remain on the books. The overuse and deliberate misinterpretation of these already convoluted and ill-fitting laws has become an “income supplement for poorly paid cops,” she explained. “In Kenya, you’ll hear the joke that cops can put out a roadblock, and that’s their payday.”

For their part, the police see the matter differently. The cops I spoke to told me that all they’re doing is following the law and bringing a person in for arrest. They said it’s up to a judge to determine whether a case merits a trial and jail time; they don’t want to overstep their bounds by determining whether a case is really criminal.

And the police are not the only power brokers who benefit from this system. In Sierra Leone, prisons are funded per head: The more inmates they have, the larger their budget. And even as the Sierra Leonean judges I interviewed bemoaned the overuse and misuse of petty offenses, they also pointed out that such laws can help maintain a certain level of social order. The Larceny Act, for example, is a useful tool to enforce the repayment of loans in a country where nearly everyone relies on debt to get by, keeping debtors in line and promoting a culture of responsibility and frugality. It’s much the same with other petty offenses: The risk of being arrested for disorderly conduct helps tamp down political protest; the threat of a loitering charge keeps poor people and those who don’t fit into the social order, such as sex workers, out of public sight. Reflecting on the history of these laws working to “cleanse white spaces” during colonialism, as she put it, Edwards remarked, “Now we’ve got independence and are self-governing, but it’s still the political and economic elite who are trying to clean these spaces.”

At least some recognize that this is an untenable system. While I was waiting with two AdvocAid paralegals for approval to go into the Female Correctional Center in Freetown, a middle-aged police officer, passing the time, complained at length about the treatment of poor prisoners. He said he knew of a few young men who had recently been charged with rape because they were considered vagrants—a way to use the law to get unwanted people out of a community. “It was like this before the war,” he told the paralegals, referring to Sierra Leone’s civil war, which spanned the years 1991 to 2002. Back then, police acted with the same broad discretion. “That’s why, if you were an officer, [the rebels] targeted you”—for amputations, for violence. During the war, the man had been recognized as a cop but survived through the kindness of one neighbor and by hiding in the forests for months, getting by on little food and water. If violence were to return, he predicted, he and other police would be targeted, “because the abuse hasn’t changed.”

Despite the broad recognition that overcriminalization has reached crisis levels, acknowledging there’s a problem isn’t the same thing as fixing it. In her work advocating for reform across the continent, Edwards says, she has spoken to lawyers, government officials, cops, and judges, “and they’ll all agree that this is a problem, but getting the system to change is incredibly difficult.”

There have been piecemeal attempts at reform—and, recently, some encouraging successes. In 2017, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights adopted principles on decriminalizing petty offenses, a nonbinding “soft law instrument to guide states,” Edwards explained (the African Commission is essentially the human rights arm of the African Union). In Malawi, litigation brought by a street vendor with the support of two NGOs resulted in the “rogue and vagabond” offense being struck from the penal code. And in early November, the court of the Economic Community of West African States, or ECOWAS, ruled that Sierra Leone must repeal, without delay, its vagrancy laws, which include prohibitions on “loitering,” as they violate the rights outlined in the African Charter. The ruling came in response to a case brought by AdvocAid and the Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In response to the ECOWAS court ruling, a spokesperson for the government of Sierra Leone told The Nation that it “is in the middle of major legal reforms” and added that the decision “aligns with Government’s ongoing efforts to bring [our laws] in line with human rights standards. This includes decriminalizing and declassifying petty offenses.”

Thus far, only one law, which considers how arrests can be conducted, has been repealed and replaced with an updated statute. Others, including those regarding debt and traffic offenses, remain on the books in Sierra Leone, while other petty offense laws are still in place in 33 countries in Africa, according to Amnesty International. The spokesperson for the government of Sierra Leone reiterated that it is committed to “reviewing outdated laws…to ensure that poverty and status are not criminalized.”

In the meantime, as they await these bigger reforms, Edwards and her colleagues, as well as other legal advocates, have tried to convince prosecutors in West and East Africa that pursuing petty-offense cases is a “huge waste of their time.” And in South Africa and Sierra Leone, some police have been trained in how to apply the laws more discerningly in the hope that this may help reduce the frequency of arrests.

Despite such changes, the underlying fundamentals haven’t shifted: Cops remain poorly paid and often have an incentive to arrest as many people as they can, and judges and politicians still want to keep the streets “clean.” After the “rogue and vagabond” offense was removed from Malawi’s penal code, Edwards has been told by cops that they simply charge people with other offenses: “We just use ‘idle and disorderly’ now,” they said. “We got rid of some section A, but we’ve still got Section B.”

Because the reform efforts of organizations like AdvocAid have, until recently, met with limited high-level success, much of their work has been focused on maneuvering within the existing legal system. Paralegals make up the bulk of AdvocAid’s workforce. They can ask for the organization’s lawyers to take up a particularly egregious case; advocate that a client’s case file be moved to the top of a judge’s pile; and make their clients’ lives a little easier by bringing extra food and clothing to people who are incarcerated and providing financial support to those who are finally released. But these are ultimately small interventions in a fundamentally broken system. Because many of the laws are so archaic and so routinely misused, the paralegals I observed spent the bulk of their time explaining the ill-fitting laws to defendants, outlining the details of how they would be unfairly wielded against them: “This is why the officer says you are criminally responsible for this debt.” “This is what he says you must do to make bail.” “This is why the judge won’t hear your case today and when he might hear it next.” They aren’t there to fix the system, but to translate its harms to its victims.

The government of Sierra Leone has also set up a Legal Aid Board to provide advice, and sometimes representation, to the country’s indigent—which, in one of the poorest countries in the world, turns out to be most of the population. The board’s support is nominally free, although one of its paralegals told me, “We ask [clients] for anything they can [give] to help us.” (Some of the paralegals are considered “volunteers” and are not on the payroll, so these informal “tips” make up whatever income they get.) Several of the prisoners I met in Makeni told me they hadn’t seen their Legal Aid representative for months. They assumed this was because they were unable to pay, although the delay may have been because there was only one lawyer, supported by two full-time paralegals and three volunteer paralegals, representing the entire northern part of the country. The small team was overwhelmed with cases, attending hearings in multiple provinces. When I visited the Legal Aid Board’s Makeni office, I had to wait several hours because the lawyer and the paralegals were in an entirely different province, several hours away, attending court.

During the Kono High Court session I attended, a Legal Aid Board team, made up of two lawyers and two paralegals, represented nearly all of the 80 cases heard, which ranged from murder to rape to diamond theft to petty debt. Each case commenced with the audible shuffling of a huge pile of papers, as a paralegal hurried to find the correct document for a particular defendant.

“We come to court, and we’ve never met with the defendant before, and yet we try to read the file quickly and do free service,” Ibrahim Mansaray, a lawyer for the Legal Aid Board’s office in the province, told me. When handed a file by his paralegal, the two would confer in hurried whispers on what it was about: “This one is for murder,” “This is for theft,” and so on, while the judge looked on.

Throughout the trials, Mansaray—who took the job after retiring from private practice—was jovial but appeared tired, running his hands through his gray hair at the end of each day. “This is the only way the government has thought of addressing this issue of poverty,” he told me during a break in the session. In most cases, he used one of two tactics: requesting that the defendant be granted bail so she could go home while awaiting more hearings, or encouraging the defendant to plead guilty in order to get a lenient sentence.

At the end of one long day, I asked Mansaray whether this felt like justice: to be forced to comply with a legal system that was antiquated, ill-fitting, and misused, to represent so many poor people who were locked up for stealing garden tools or food from a neighbor. All of this was avoidable—the laws could be changed, the colonial-era acts finally overturned. Mansaray agreed it was a shame, but he was stressed and overworked and had a specific job to do. With 15 minutes per case, he felt hamstrung. “We too are just humans,” he reflected. “We can only do so much.”

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation