South Korean Protesters Thwarted More Than Just a Coup Attempt

The uprising against South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol prevented him from seizing dictatorial powers. It may also help avoid a cold war with China.

People protesting South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol chant slogans as they attend a candlelight rally outside the National Assembly Building, in Seoul, South Korea, on December 4, 2024. Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law in the late hours of December 3.

(Daniel Ceng / Anadolu via Getty Images)

In August 2023, US President Joe Biden hosted South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio at Camp David, where the three celebrated their “shared democratic values.” This week—less than 18 months later—Yoon attempted to seize dictatorial power in a coup.

How did we get here? And what happened? Events are moving quickly, but the crisis began when Yoon announced Tuesday night that he was implementing emergency martial law, citing gridlock in the National Assembly and the subversive danger posed by the opposition. As tanks rolled through Seoul and helicopters circled, Yoon sent troops into the Assembly to potentially arrest legislators. Police outside attempted to block others from entering, since the opposition has a sizable majority and could overturn his declaration with a vote. The South Korean people—who have experience defeating dictators, prospective or otherwise—sprang into action, massing near the Assembly and helping legislators enter the building. The National Assembly soon voted 190–0 to rescind martial law. After only a few hours, Yoon announced that he was standing down. His attempt to seize power had failed. He will likely be impeached.

Yoon—a former prosecutor general—became president in 2022 after a razor-thin victory over liberal candidate Lee Jae Myung. His administration has since been plagued by numerous scandals and accusations of corruption, some involving his wife, Kim Keon Hee. Yoon already faced a hostile legislature, but after an electoral rebuke this year in which the opposition gained even more seats, Yoon especially struggled to enact policy. Indeed, the trigger for the coup was the National Assembly’s cutting his preferred budget and planning to impeach the head of the state audit agency and prosecutors who declined to indict the first lady. Yoon is extremely unpopular in South Korea, and has been for much of his presidency. For context, a recent news article reported that Yoon’s approval rating had risen for the second consecutive week—which sounds like good news, until you realize that it rose to a mere 25.7 percent. His coup attempt failed in part because he lacks popular support.

This shouldn’t be surprising: Yoon is a petty tyrant. He organized the first military parade through Seoul since fellow aspiring dictator Park Geun Hye was run out of office by the Candlelight Revolution of 2016–17. This year’s parade took a page from North Korea and showcased a ballistic missile, which is ironic since Yoon has repeatedly tarred his domestic opposition as secret supporters of the North. In an August 2023 speech—a few days before he visited Camp David—Yoon warned of a fifth column of “anti-state forces” working to destroy South Korea from the inside out. “The forces of communist totalitarianism,” he declared, “have always disguised themselves as democracy activists, human rights advocates, or progressive activists while engaging in despicable and unethical tactics and false propaganda.” Yoon similarly cited the threat posed by “anti-state elements” and North Korea sympathizers when he announced the imposition of martial law.

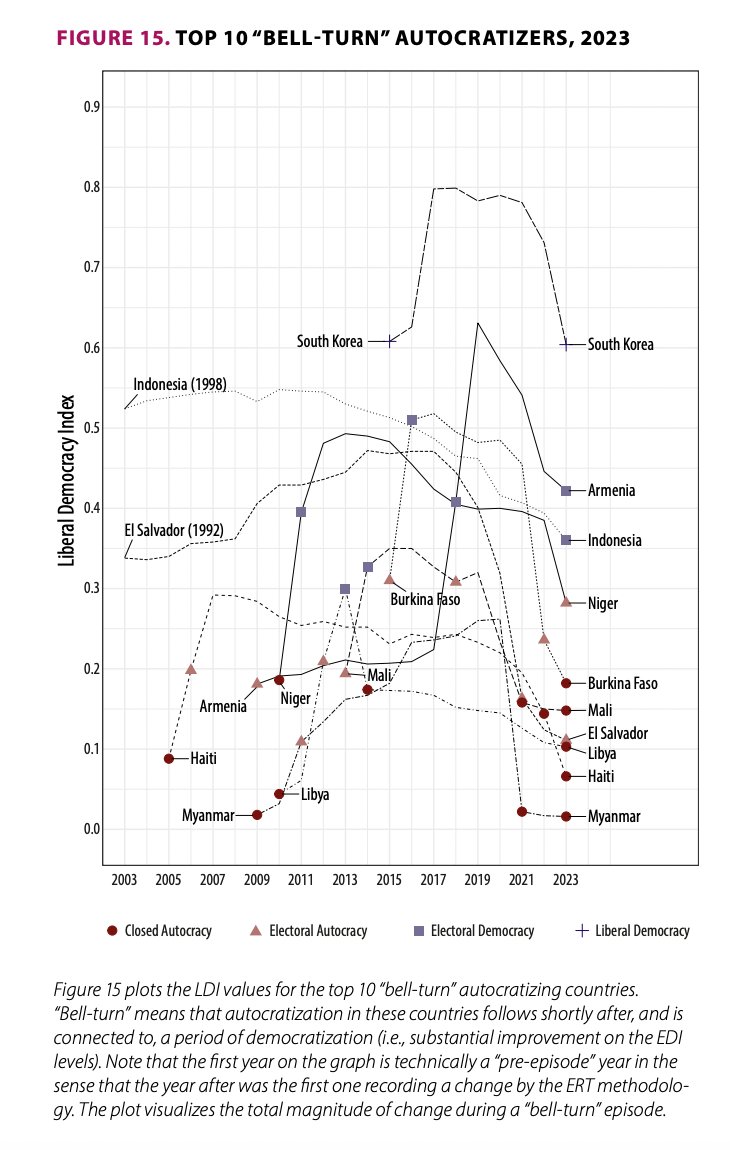

Yoon’s authoritarian bent has not gone unnoticed. Reuters reported on his red-baiting of domestic critics, and journalist E. Tammy Kim warned in The New Yorker of Yoon’s democratic backsliding, particularly on freedom of the press—including raids against journalists perceived to be hostile to the administration. The situation is so bad that this year the V-Dem Institute, which publishes a report on the state of world democracy, included South Korea in its top 10 list of “bell-turn” autocratizers. In other words, South Korea—which only transitioned to democracy in the late 1980s and ’90s—is now going backward. One chart in the report shows a literal authoritarian turn under Yoon.

If you are an American who knew none of this, you’re not alone. Even if you’re an avid reader of world news, the chances are, you only knew two things about Yoon: (1) He once sang Don McLean’s interminable boomer hit “American Pie”; and (2) he patched up relations with Japan to help the US counter North Korea. The first of these is—sadly—true.

The second is at best incomplete.

The story told about Yoon by Joe Biden and some US think tanks is that he’s a visionary peacemaker and committed democrat who set aside historic South Korea–Japan tensions to foster trilateral security cooperation and deter North Korea. The joint Camp David statement, for instance, says Biden “commended President Yoon and Prime Minister Kishida for their courageous leadership in transforming relations between Japan and the ROK.” But Yoon was willing to expand cooperation with Japan for an obvious reason. He is a South Korean conservative, and South Korean conservatives are soft on the legacy of Japanese imperialism. Why? Because many of them were collaborators.

Yoon’s reproachment with Japan is controversial in South Korea not because it’s with Japan per se but because he refuses to hold Japan accountable for forced wartime labor. Indeed, the “settlement” that laid that the groundwork for security cooperation was really Yoon putting South Korea—rather than Japan—on the hook to compensate the victims of colonial occupation. This is not ancient history. Around 1,800 former forced laborers are still alive in South Korea.

More on South Korea:

And while South Korea and Japan are neighbors to North Korea and subject to its missile tests, trilateral cooperation has bigger fish to fry. It is aimed at China, much like the AUKUS agreement to provide Australia with attack submarines and Biden’s foreign policy generally. Essentially, Biden viewed Yoon as a convenient vehicle for his global strategy of great-power competition. Like most South Korean conservatives, Yoon aligns with the United States on foreign policy and was seen as a reliable partner against China. Since he took power in 2022, the US has expanded its presence in Northeast Asia and engaged in nearly constant military exercises—some of which are now trilateral joint drills. Ostensibly, US-led security cooperation seeks to deter North Korea, but ultimately it aims to establish a regional anti-China bloc.

In the United States, the Cold War was depicted as a battle between communism and “the free world.” But of course, the “free world” was a misnomer. Sure, the US bloc contained liberal democracies, but it also included countries under dictatorial rule—like, for instance, South Korea. Washington propped up these dictators because they were seen as reliably anticommunist, allowing their country to be used as a pawn in the larger game of checking Soviet power.

I dislike facile Cold War comparisons, but here the connection seems warranted. The Biden administration, determined to counter China, papered over Yoon’s authoritarian qualities because he was an asset in a great-power competition. In an echo of Cold War rhetoric, Biden portrayed an unpopular and tyrannical leader as a proponent of democracy, gambling that Yoon would never go so far as to blatantly expose the charade. Biden was wrong.

If there is an upside to this whole affair, it is that Yoon’s amateurish coup attempt will forever associate his policies with authoritarianism. Trilateral security cooperation was already controversial in South Korea. Now it may be radioactive. In that sense, we should all thank ordinary South Koreans, who thwarted not only Yoon’s dictatorial ambitions but potentially US aims that could have led to war with China. For that, the world owes South Korea a great debt.