Spain’s Left Is in Turmoil—and the Right Has Gone Nuts

Chaos has hit both wings of Spanish politics—but while the left is still in government, conservatives have turned to Trump-style conspiracy theories.

It only took three weeks for Spain’s new coalition government to suffer its first internal crisis. On December 5, Javier Sánchez Serna, the spokesperson for Podemos, the left-wing party that burst onto the Spanish political scene nearly 10 years ago and has been in a tense but steady partnership with the ruling center-left Socialist Party (PSOE) since 2019, announced that its five parliamentarians were abandoning the coalition. “We have tried to do everything we could within Sumar,” he said, referring to the left-wing government grouping led by Labor Minister Yolanda Díaz. “But it has proved to be impossible.”

On November 16, Podemos and the other parties that make up Sumar, as well as six regional nationalist parties from across Spain, had helped vote in Pedro Sánchez, the leader of the PSOE, as prime minister. The vote secured him a parliamentary majority for a second term at the helm of a progressive coalition, following elections in July that failed to produce an expected right-wing majority. During Sanchez’ first full term, which lasted from 2019 to 2023, his coalition partner was Unidas Podemos, which included Podemos and the long-established United Left party. This time, however, Unidos Podemos was supplanted as the linchpin of the coalition’s left wing. That role now belongs to Díaz and Sumar, an alliance that includes more than twenty green, democratic socialist, and other left-wing parties—but that now does not include Podemos.

Weeks before the vote, Sánchez and Díaz agreed to an ambitious legislative program that, if followed, could significantly improve day-to-day life for millions of Spaniards. A headline in El País, the country’s paper of record, singled out the fact that the parties had pledged to establish a 37.5-hour work week. Yet it is the seemingly smaller-ticket measures that could result in the biggest social and economic improvements. These include expanding public housing, family leave, and investment in the public healthcare system as well as universal public childcare; measures to address youth unemployment; stricter regulation of firing for just cause; and closer adherence to the European Social Charter, which guarantees a set of basic rights to people in the EU.

The Podemos defections have wrenched attention away from this agenda. Its leaders say their decision to break with Sumar just weeks into the new term will give the party and its representatives more media visibility and independence to challenge the government. (The breakaway deputies from Podemos were quick to assure voters that they would continue to vote with the governing coalition on important legislation.)

The last straw for Podemos, the party claims, was a recent parliamentary debate over the war in Gaza. Party leader Ione Belarra and others were barred by their coalition partners from speaking on the issue before parliament. It was not the first time the war in Gaza has come up to explain the mounting tension between Sumar and Podemos. During the negotiations to form a minority coalition government, Podemos leaders also pointed to Belarra’s statements about Israeli human rights violations as the reason behind Sánchez’s decision not to reappoint her as Minister of Social Rights. Pablo Iglesias, a founder and former leader of Podemos who has left active politics to lead a new far-left media company, claimed Belarra had been “dismissed.” International media figures such as Shaun King took the headline and ran with it, saying she had been “fired and removed” for her statements on Gaza.

But this phrasing confuses interparty negotiations with dogmatic tactics. Close observers of the long-standing tension between the two parties, such as the Irish journalist Eoghan Gilmartin, have described the decision to replace Belarra as “a question of contested leadership on the radical left”: “Her position on Palestine,” he added, “has basically nothing to do with the decision.” In place of Belarra, the government appointed Sira Rego, a former member of the European Parliament for the United Left who is of Palestinian descent and spent part of her childhood on the West Bank. Prime Minister Sánchez, meanwhile, has taken advantage of Spain’s six-month turn at the head of the European Union to call for a cease-fire in Gaza and criticize Israel’s bombing of civilian targets.

Like most of the rifts that have plagued the political space to the left of the Socialist Party for the past decade, the disagreements between Podemos and Sumar have been less over policy than power—and less a matter of substance than of style. Worse, they have taken the form of public shouting matches in which party leaders accuse each other of disrespect and disloyalty. The rapidly dwindling core of Podemos loyalists feels that Díaz and Sumar have gone out of their way to humiliate the party. The clearest example they point to is the fact that, after holding two ministerial positions in the last Sánchez government, the party was given none in the present government, despite legislative achievements on sexual consent, gender identity, and animal rights.

Those who’ve joined Sumar, in turn—including scores of talented Podemos leaders who have left the party amid a wave of expulsions and defections—argue that Podemos’s claims to primacy and ideological purity are a recipe for demobilization and divisiveness. The only reason Podemos was able to win any deputies in the July elections, they say, was because of its alliance with Sumar. The party’s dismal results in local and regional elections this past May, before it joined Sumar, confirmed a long downward spiral.

The truth is that Podemos joined Sumar reluctantly. In June, at the last possible moment, the parties reached an agreement following drawn-out negotiations that concluded with the exclusion of Irene Montero, until then the minister of equality, from the electoral lists. Podemos claims that Díaz personally vetoed Montero, who is also Iglesias’s life partner. Sumar maintains that Podemos agreed to drop her in exchange for a larger share of the state subsidies reserved for political parties. Yet, by leaving the government now, the party is breaking a number of the agreements it struck in June, including the understanding that all the parties under the Sumar umbrella would remain united in a single parliamentary group that would last for “the duration of the legislature.”

Perhaps most shocking, however, is that the decision to leave was taken without consulting voters—many of whom had rallied around the idea of a unified left when they cast their ballots in July. The decision to break that alliance even caught some prominent Podemos party members by surprise. “I just found out from Canal Red [Pablo Iglesias’s online television channel] that we are going to the opposition,” Carolina Alonso, the former spokesperson for Podemos in the Madrid region, posted on the social media platform X.

Yet many have also partially blamed the breakup on Díaz and Sumar. “Díaz could have avoided this hit,” the journalist Pablo Elorduy wrote in El Salto, pointing to Díaz’s unwillingness to include Podemos members in a series of key parliamentary appointments. Now, Elorduy added, “Sumar will have an opposition to its left that will be free of commitments to the government.” When the government will be forced to negotiate with Podemos to secure its support for key pieces of legislation, including the national budget, Podemos will “claim all the wins,” Elorduy predicts. Sumar, in turn, will find it more difficult to avoid being seen as the handmaiden to its senior coalition partner, the PSOE, which has been steadily expanding its share of the vote at the expense of the parties to its left.

This was not the first time a political coalition led by Yolanda Díaz had suffered internal problems that led to defections. In 2012, when Díaz presided over a coalition in the Galician regional parliament, in the northwest of Spain, internal clashes led to three representatives leaving the coalition to join the opposition, just as with Podemos. Later, Xosé Manuel Beiras, the longtime leader of left-wing Galician nationalism, would charge Díaz with having “used” the regional coalition “to make a political career in Madrid” rather than represent the Galician people. “Yolanda Díaz,” he claimed, “was the first person who betrayed me.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The left may be in some turmoil, but it’s also still in government. The same can’t be said for Spain’s right-wing parties, which were thought to have a lock on power ahead of the election, only to see Sánchez squeak by yet again. The conservative Popular Party (PP) and the far-right Vox still seem to be in denial about their failure to secure enough seats to form a government. Instead of accepting their defeat, the right has turned to Trump-style conspiracies, calling Sánchez’s reappointment as prime minister “electoral fraud.” Key to this right-wing mobilization is the fact that Sánchez’s supporters in parliament include parties from Catalonia and the Basque Country who favor independence for their regions. Sánchez secured the support of the Catalan parties by promising amnesty for some 300 politicians and activists who are facing prosecution for their role in the 2017 referendum on Catalan independence, which the national government had declared illegal.

According to polls, close to two-thirds of Spaniards oppose the amnesty, and Sánchez himself had ruled out during his election campaign, only to reverse course in his quest to form a government. The PP and Vox have vowed to slow down the amnesty bill in the Senate, which has a right-wing majority, and to question its constitutionality in Spanish and, if necessary, European courts. In an unprecedented move, professional associations of judges and prosecutors have also voiced opposition to the amnesty, claiming that it subverts the rule of law.

In addition to legal procedures, the PP and Vox have also taken to the streets and the airwaves. On December 6, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, the leader of the PP, railed against the new left-of-center government during a ceremony commemorating the 45th anniversary of Spain’s post-Franco Constitution. Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, he said, “is leading a movement against the Constitution.” Those to Feijóo’s right, such as Vox leader Santiago Abascal, have been even less cagey, claiming that to bring Catalonia’s politicians into the democratic fold through amnesty is tantamount to “golpismo,” or launching a coup d’état. On November 13, during the week of the investiture debate, Tucker Carlson, the former Fox News star, visited Madrid to participate in the 11th night of far-right-led protests against the Spanish government, which that day filed the amnesty bill.

These protests, which concentrated at the PSOE’s party headquarters, drew far-right fringe groups who waved swastika flags, made fascist salutes, and even accused the Spanish king of having joined the conspiracy by allowing Sánchez to be sworn in. Carlson’s assessment was as inflammatory as it was clear: “The left in Spain is trying to take over the country extralegally, offering amnesty to terrorists, against the Constitution, in order to take complete control.”

“Anybody who would violate your Constitution, potentially use physical violence to end democracy,” Carlson said, echoing the protestors, “is a tyrant, is a dictator.” “There will come a time when the Spanish people will want to hang Sánchez by his feet,” Abascal told the Argentine newspaper Clarín, in a reference to Benito Mussolini, when he was in Buenos Aires to attend the inauguration of far-right presidential candidate Javier Milei on December 10.

What right-wing leaders and protesters have yet to acknowledge is that the bill proposed by Sánchez also includes an amnesty for the police, whose violent crackdown on voters during the 2017 Catalan referendum made international headlines. As an editorial in the Financial Times argued, “Spain has introduced amnesties before and the public interest case here is compelling.… It is also a political dead end for the PP if it only sees eye to eye with the far-right.” The bill would make necessary democratic advances to Spain’s quasi-federal system and temporarily solve one of the most challenging political puzzles in Europe: regional independence movements. The Spanish right, by contrast, has been unable to formulate a political alternative to diffusing Spain’s territorial tensions.

Instead, it is betting on short-term electoralism, hoping that Spaniards’ opposition to Catalan amnesty will help the PP defeat the PSOE in the elections for the European Parliament, scheduled for next June. By placing all its bets on culture wars, as it did this past July, the right reveals its lack of confidence in the ability of its political programs to generate popular support.

What’s most concerning, however, is that the right-wing opposition to Sánchez is playing a dangerous game of political amnesia. In their extreme rhetoric over the amnesty bill, the Spanish right is erasing its own past, which includes an important legacy of reaching agreements with pro-independence parties. Rather than negotiate with Catalan nationalists, as former prime minister and PP-leader José María Aznar did in 1996 to form his own government, Aznar and other conservatives are today championing protests defined by Nazi flags. In fact, they appear to be following a playbook developed in recent years by Carlson and the American right. The Spanish right’s use of conspiracy theories and extreme rhetoric to drum up nationalist opposition to the Sánchez government will only undermine the legitimacy of the very political institutions they claim to defend.

Time is running out to have your gift matched

In this time of unrelenting, often unprecedented cruelty and lawlessness, I’m grateful for Nation readers like you.

So many of you have taken to the streets, organized in your neighborhood and with your union, and showed up at the ballot box to vote for progressive candidates. You’re proving that it is possible—to paraphrase the legendary Patti Smith—to redeem the work of the fools running our government.

And as we head into 2026, I promise that The Nation will fight like never before for justice, humanity, and dignity in these United States.

At a time when most news organizations are either cutting budgets or cozying up to Trump by bringing in right-wing propagandists, The Nation’s writers, editors, copy editors, fact-checkers, and illustrators confront head-on the administration’s deadly abuses of power, blatant corruption, and deconstruction of both government and civil society.

We couldn’t do this crucial work without you.

Through the end of the year, a generous donor is matching all donations to The Nation’s independent journalism up to $75,000. But the end of the year is now only days away.

Time is running out to have your gift doubled. Don’t wait—donate now to ensure that our newsroom has the full $150,000 to start the new year.

Another world really is possible. Together, we can and will win it!

Love and Solidarity,

John Nichols

Executive Editor, The Nation

More from The Nation

Brace Yourselves for Trump’s New Monroe Doctrine Brace Yourselves for Trump’s New Monroe Doctrine

Trump's latest exploits in Latin America are just the latest expression of a bloody ideological project to entrench US power and protect the profits of Western multinationals.

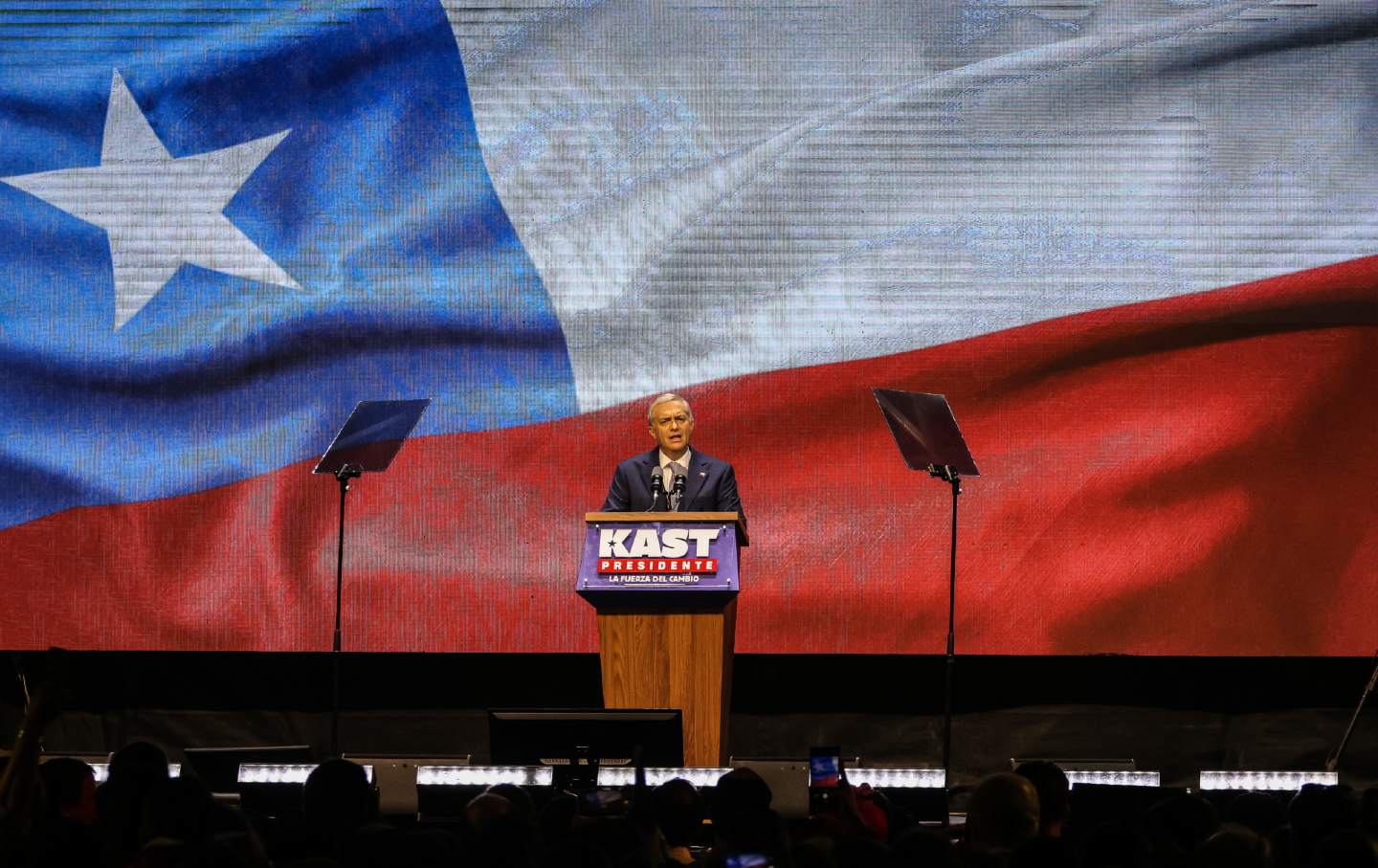

Chile at the Crossroads Chile at the Crossroads

A dramatic shift to the extreme right threatens the future—and past—for human rights and accountability.

The New Europeans, Trump-Style The New Europeans, Trump-Style

Donald Trump is sowing division in the European Union, even as he calls on it to spend more on defense.

The United States’ Hidden History of Regime Change—Revisited The United States’ Hidden History of Regime Change—Revisited

The truculent trio—Trump, Hegseth, and Rubio—do Venezuela.

Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda

In his new book Slow Poison, the accomplished anthropologist revisits the Idi Amin and Yoweri Museveni years.

The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day

We may already be on a superhighway to the sort of class- and race-stratified autocracy that it took Russia so many years to become after the Soviet Union collapsed.