The Impossibility of Reporting the Story of Gaza

The work of Gaza’s journalists has been essential these past months, but as the challenges of reporting continue to mount, the world is getting only a fraction of the story.

Samer Abu Daqqa loved being a journalist. A cameraman for over 20 years with Al Jazeera, Abu Daqqa, 45, had covered at least seven wars. Israel’s war on Gaza, however, would turn out to be his last.

While covering an air strike at a United Nations–run school on December 15, Israeli forces shot Abu Daqqa. Intense shelling prevented an ambulance from reaching him—three paramedics were killed trying to get to the area—and he was left to bleed for over five hours, succumbing to his injuries just as the Palestinian Health Ministry got approval from the Israeli military to retrieve him. In the end, they brought his body to the hospital, where his family said goodbye. Medical workers removed his bloodied press vest and helmet, which were placed over his body at his funeral.

Since the beginning of Israel’s war on Gaza, which has now killed more than 20,000 Palestinians, journalists have been on the front lines, both as witnesses and victims. For more than two months, as Israel has rained bombs on Gaza, they have rushed from refugee camps to hospitals, and from hospitals to schools and back, trying to stay safe while covering what they describe as their own genocide. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 68 journalists have been killed in Gaza, Israel, and Lebanon since October 7, making this the deadliest conflict since the CPJ began tallying press fatalities. The International Federation of Journalists estimates that at least 66 journalists have been killed in Gaza alone. Many have also lost their families. On October 26, Ahmed Abu Artema, a contributor to The Nation as well as a poet and activist, was seriously injured and lost his young son when Israel bombed his father’s house.

“What is happening now is unprecedented,” said Sherif Mansour, the Middle East and North Africa program coordinator at the CPJ. In 2022, the CPJ reported that a total of 68 journalists and media workers were killed worldwide; Gaza reached that number in just over two months.

Journalists, said Mansour, “are the ones on the front lines and they are the ones we need the most, but they are also the most vulnerable.”

It’s hard to overestimate the importance of the Palestinian journalists in Gaza right now. They, after all, are the only ones who have been reporting from the Strip since Israel instituted a total siege on October 9 and banned foreign press from entering. Their work has been essential and their commitment unceasing; yet, as the weeks have passed, the mounting challenges of reporting have meant that the world outside of Gaza is getting only a fraction of the story. Even social media has offered only a partial solution, as many of the platforms regularly censor Palestinian voices.

By far, the biggest challenge for journalists is simply staying alive. The struggle to survive while reporting is an all-consuming endeavor. But this struggle has been seriously compounded both by the conditions of war and the shattering effects of Israel’s total siege of the Strip. Food and water are scarce; fuel is dwindling, electricity inconsistent, and cell phone service undependable; many journalists no longer even have homes to return to.

For journalists, this has meant everything from reporting on empty stomachs to writing up stories while worrying about when and how they will find water. One journalist has used Gaza’s salty seawater to bathe, and another said he shared half a liter of clean water for four days with colleagues. Meanwhile, it has become normal to wait for food in hours-long lines and still not manage to buy anything, said Nazar Sadawi, a correspondent with Turkish Radio and Television. “I don’t have the luxury of time. I don’t have 10 hours to wait for my turn,” he said, explaining that instead he lives mostly off of bread, tea, and biscuits. “Aid trucks bring in canned beans, water, and some medicine, but it doesn’t even meet 5 percent of the need. We can literally reach a famine.”

Sadawi left the north for the south after Israel issued an evacuation warning on October 11 to the entirety of north Gaza’s 1.1 million people. “You can call me homeless” or a “displaced person,” he said. The neighborhood around his home has since been bombed, and his parents’ house as well as his car have been destroyed in Israeli air strikes. With whole buildings either completely or partially destroyed, finding anywhere with a bed or couch is near impossible. Sadawi is lucky to get two to three hours of sleep, he said, usually on a hospital chair on the sidewalk, and without a blanket. “I don’t have clothes. I left those at home,” he said. The hospital is also where he showers and uses the restroom, which also requires waiting in hours-long lines.

Meanwhile, Sadawi said, the frequent shutdowns of Internet and cellular service have meant that reporting has reverted to old-school methods—trekking from area to area over debris and destroyed roads, surveying survivors and witnesses for casualty numbers, and listening to the radio for context and conditions. “The news that I used to get in three minutes I now get in an hour or two,” he said.

Before Gaza lost consistent access to the Internet and cellular service, journalists used to call each other to swap information. But now, “I call the people who are covering air strikes 20 times for the line just to connect, and just so I can check on if they’re still alive,” he said. Satellite phones could solve this, but Sadawi said it’s impossible to obtain one now given the blockade. “Only five journalists probably have them, and they got them before the war,” he said. Often, Sadawi has to pick between calling his family or the woman he loves. “She lives somewhere I can’t reach.”

Journalists no longer keep regular working hours. Because Israel has stopped “roof knocking”—alerting people when an air strike is incoming—journalists cover the aftermath at all times of the day, but they are eager to be sheltered by sunset (around 5 pm), because shelling is strongest in pitch-black conditions. And because the bombardment is constant, the noise, as well as nightmares make it hard to sleep—something both interviews and a survey of journalists’ social media posts show.

This, along with the trauma of lost loved ones, lost homes, constant fear, and the relentless sight of death, is wreaking havoc on journalists’ future mental health, said Ghazi Aloul, a Roya News correspondent. Aloul, who has spent only six hours at home since November, is living in the same areas he is covering, relying on hospitals for rest and charging his equipment. “I have experienced many painful moments in this war,” Aloul said. “Previous wars were not this brutal.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Within this landscape of brutality, “the most sensitive scenes for me to see are children bleeding and injured, because immediately I think of my little 2-and-a-half-year-old girl,” he said. Still, he keeps working. “I try to stay firm and convey my work, photographs, and the truth, because my daughter could be among the dead, and I would need someone to convey her voice and image,” he added.

Aloul says that he himself is not afraid to die. ”If that’s my destiny, then so be it,” he said. But he cannot bear the idea of losing his loved ones. “Experiencing loss is extremely painful and unbearable, and that’s what I can’t get out of my head.”

As the stories of murdered journalists have mounted, many in Gaza have come to suspect that Israel is deliberately targeting the press. This fear became particularly acute after an Israeli air strike hit and killed the place where the family of Aljazeera’s Gaza bureau chief, Wael Aldahdouh, was sheltering. “They are taking revenge on us through our children,” he said, sitting next to his dead son’s body. On December 15, Aldahdouh was shot in the arm while reporting on an air strike on Haifa School in Khan Younis; it was during the same reporting trip that Abu Duqqa was shot and killed.

Israel’s military has repeatedly denied that it targets journalists. “The IDF takes all operationally feasible measures to protect both civilians and journalists. The IDF has never, and will never, deliberately target journalists,” a spokesperson told The Nation. “Given the ongoing exchanges of fire, remaining in an active combat zone has inherent risks. The IDF will continue to counter threats while persisting to mitigate harm to civilians.”

Yet the IDF’s actions have continued to raise questions for journalists, as have statements from the Israeli press. Hours after the strike that killed Aldahdou’s family, Avi Yehekli, of Israel’s Channel 13, said, “Generally, we know the target. Like today, there was a target on the family of an Aljazeera journalist.”

Meanwhile, as fear of being targeted by an Israeli air strike has grown, The Nation found that several journalists have pleaded with others in their profession not to add a location to their social-media posts. Aseel Moussa, a correspondent in Gaza with Middle East Eye, believes that Israel will continue to kill journalists because it has never been held accountable in the past. (From 2000 to 2022, Israel killed 55 Palestinian journalists, according to the Palestinian News Agency. Last year, Israel admitted, after several months of denials, that it was responsible for shooting and killing Palestinian-American Shireen Abu Akleh.)

“There is nowhere safe in Gaza for anyone of any profession,” said Moussa, who evacuated eastern Gaza for the south last month only to be met with more bombing. Two days before our interview, Moussa said, her relatives’ home was hit, killing nine family members. Seven were children.

Compounding all of these horrors is the painful reality that, even when journalists do manage to report, their stories can have limited reach. For years, digital rights groups and tech watchdogs have claimed that Meta censors content related to Palestine and that it also monitors Arabic content more excessively than it does Hebrew content. Last week, Human Rights Watch found that Meta systematically censors Palestinian content around the world.

This kind of shadow banning, as it is called, stymies the world’s access to content coming out of Gaza. Motaz Azaiza, a photojournalist who has gained a global following of over 17 million followers on Instagram and was named GQ Middle East’s Man of the Year, shared screenshots from Meta indicating that he’d violated Instagram’s community guidelines for posting images; he also shared notifications alerting him that some of his content had been taken down. Meta has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

Still, despite the mounting threats and dangers, what matters to Middle East Eye’s Moussa most is his work. “When I can’t publish my articles or cover the stories around me, that’s when my feelings of helplessness deepen,” he said.

And so, journalists keep reporting, knowing that it might lead to their death. In the last month, several journalists have written their own anticipated obituaries online, sharing their last words, and predicting their own deaths. Roshdi Sarraj, an admired journalist whom Moussa described as “at the top of the field,” was one of them. In one of his last personal posts, Sarraj wrote on Facebook: “We will not leave. And when we do leave Gaza, we will go to the sky, and the sky only.” He was killed days later in an air strike, survived by his wife and baby girl, who turned 1 on November 6.

Time is running out to have your gift matched

In this time of unrelenting, often unprecedented cruelty and lawlessness, I’m grateful for Nation readers like you.

So many of you have taken to the streets, organized in your neighborhood and with your union, and showed up at the ballot box to vote for progressive candidates. You’re proving that it is possible—to paraphrase the legendary Patti Smith—to redeem the work of the fools running our government.

And as we head into 2026, I promise that The Nation will fight like never before for justice, humanity, and dignity in these United States.

At a time when most news organizations are either cutting budgets or cozying up to Trump by bringing in right-wing propagandists, The Nation’s writers, editors, copy editors, fact-checkers, and illustrators confront head-on the administration’s deadly abuses of power, blatant corruption, and deconstruction of both government and civil society.

We couldn’t do this crucial work without you.

Through the end of the year, a generous donor is matching all donations to The Nation’s independent journalism up to $75,000. But the end of the year is now only days away.

Time is running out to have your gift doubled. Don’t wait—donate now to ensure that our newsroom has the full $150,000 to start the new year.

Another world really is possible. Together, we can and will win it!

Love and Solidarity,

John Nichols

Executive Editor, The Nation

More from The Nation

Brace Yourselves for Trump’s New Monroe Doctrine Brace Yourselves for Trump’s New Monroe Doctrine

Trump's latest exploits in Latin America are just the latest expression of a bloody ideological project to entrench US power and protect the profits of Western multinationals.

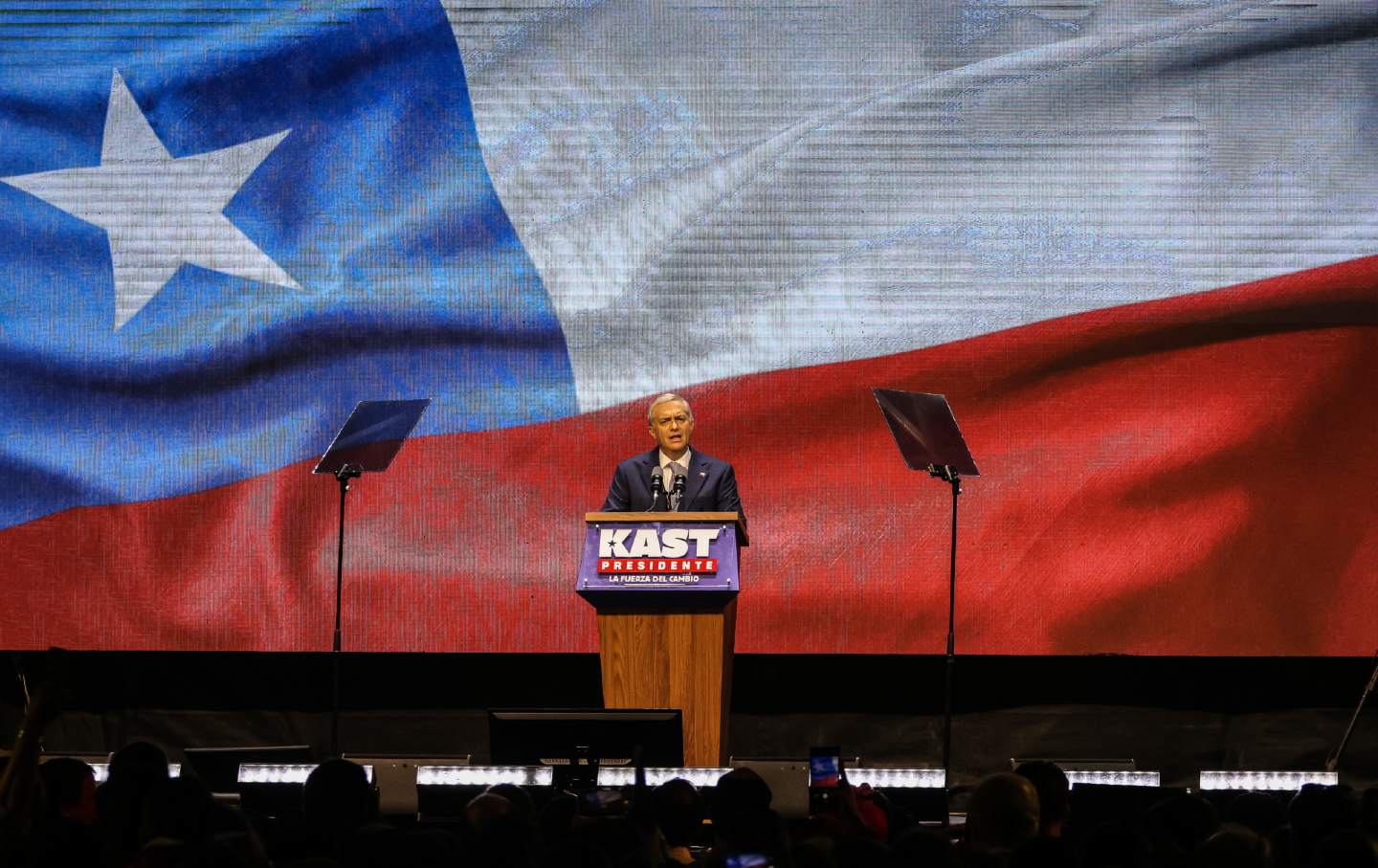

Chile at the Crossroads Chile at the Crossroads

A dramatic shift to the extreme right threatens the future—and past—for human rights and accountability.

The New Europeans, Trump-Style The New Europeans, Trump-Style

Donald Trump is sowing division in the European Union, even as he calls on it to spend more on defense.

The United States’ Hidden History of Regime Change—Revisited The United States’ Hidden History of Regime Change—Revisited

The truculent trio—Trump, Hegseth, and Rubio—do Venezuela.

Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda

In his new book Slow Poison, the accomplished anthropologist revisits the Idi Amin and Yoweri Museveni years.

The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day

We may already be on a superhighway to the sort of class- and race-stratified autocracy that it took Russia so many years to become after the Soviet Union collapsed.