The Invisible Lives of Israel’s Thai Workforce

Manee Jirchat was one of the 31 Thai laborers kidnapped by Hamas on October 7. This is his story.

On the morning of October 7, Manee Jirachat, a Thai laborer residing at Kibbutz Re’im in southern Israel, was speaking to his father, Chumporn, on the phone. It was one of two calls he made daily to his parents back in Thailand to check in. Manee told his father about the gunfire he’d heard that morning. Then the warning sirens began to blare.

“Go to the safe room,” Chumporn, who had worked on the same kibbutz years earlier, told his son.

Manee and five other Thai workers piled inside the safe room and waited, thinking that the warning would be over quickly; after all, that’s what usually happened. The six men left when the sirens stopped, Manee recalled, but when the wailing started up again, they ducked back into the cramped room, where the reinforced walls were built to protect the occupants from gunfire and explosions.

When Manee and the others exited the safe room a second time, they ran into a group of armed men. Manee initially assumed they were Israeli soldiers, but their yelling and the unfamiliar patches on their uniforms unnerved him.

The men were Hamas militants. They surrounded the workers, took away their phones, and escorted them to a pickup truck. The vehicle was too small to hold all six, Manee recalled, so the Hamas fighters executed two of the men at random. Manee and the remaining workers were then loaded into the truck with their heads down. When Manee looked up again, they were already in Gaza. “That’s it,” he thought to himself.

During the October 7 Hamas attacks on Israel, Thais suffered some of the worst losses of any nationality other than Israelis. Thirty-nine Thais were killed and 31 were taken hostage, according to a December report from Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The majority of them, including Manee, were freed during the temporary cease-fire between Israel and Hamas last year. Eight are still in captivity. Their conditions remain unknown as Israel continues to assault Gaza.

Thais constituted the largest number of migrant workers caught up in the October 7 attacks, but they weren’t the only ones. At least four Filipino caregivers, 10 Nepalese agricultural trainees, and one Cambodian student were murdered, while two Filipinos and one Nepali were taken hostage. Their fate has been largely overlooked by Israeli and Western media during the past six months, rendering them as invisible now as they were when they were working in Israel.

Despite their invisibility, foreign nationals have been vital to Israel’s economy since the government normalized imported labor in the early 1990s. Before October 7, some 149,000 foreign nationals worked in Israel, both legally and illegally, according to Israel’s Population and Immigration Authority. (Other estimates place this number much higher.) Their labor has been essential to a number of low-wage industries—agriculture, construction, and home care above all. The large numbers of Thai migrants reflect not only economic pressures within Thailand but a critical shift in Israel’s low-wage workforce, from one heavily composed of Palestinian laborers to one in which foreign workers predominate.

To understand this shift, it helps to rewind to the late 1980s and early 1990s. This was a period of dramatic economic transformation, both in Israel and elsewhere. Around this time, Israel was in the process of making a sharp neoliberal turn, casting off the vestiges of its socialist origins in favor of deregulation and liberalization. Meanwhile, globalization was accelerating around the world, sending waves of people to foreign countries in search of work. Israel was one of those taking labor in.

But economic forces don’t fully explain Israel’s move toward a foreign workforce; the change was also deeply political. Matan Kaminer, an anthropologist and lecturer in the School of Business and Management at the Queen Mary University of London, argues that Israel has used imported workers as part of a strategy “to basically wean the Israeli economy off its dependence on Palestinian labor.” It is, Kaminer says, “what is known in Israeli parlance as ‘separation,’ or you can translate into Afrikaans as ‘apartheid’ if you want.” While the strategy has never been fully realized, the goal is “separating Israelis and Palestinians from one another, including all of the economic interconnections.”

That process has only intensified since the start of the current war. Before October 7, some 192,700 Palestinians worked in Israel and the settlements, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO); 40,000 of those working in Israel were undocumented and doing so informally. About 17 percent of all Palestinians with a job worked in Israel or the settlements.

Since the Hamas attacks, around 20,000 Palestinian workers from Gaza—many employed in agriculture—have lost their jobs in Israel due to restrictions, while some 160,000 Palestinians from the occupied West Bank have lost or are at risk of losing their employment, according to an assessment by the ILO. At the same time, Israeli figures show that nearly 10,000 foreign workers, mostly Thai, left the country following the attacks—and while some 6,000 have returned in recent months, the Agricultural Ministry says the sector is still facing the greatest manpower crisis it has known since the establishment of the state. And the problem extends well beyond agriculture: Construction companies have warned of a critical shortage of workers, with one company saying that it is the “most difficult situation” the industry has faced.

Rushing to cobble together a patchwork of replacement labor as it bombards Gaza, Israel has imported agricultural workers from Malawi, Kenya, and Sri Lanka and is seeking construction workers from India, China, Moldova, Uzbekistan, and elsewhere. To speed the process, it has hurriedly rolled back some labor regulations. These developments raise questions about Israel’s long-term ability to function without its traditional reliance on Palestinian labor. They also portend a future in which the country’s entire economy resembles that of its agriculture sector, where “the vast majority of the Palestinian workforce was dispensed with,” in Kaminer’s words.

The migration of Thai farm laborers to Israel can be traced back, in part, to an ambitious West Point graduate named Pichit Kullavanich, who became a powerful general in the Royal Thai Army. Thailand, which during the Cold War was an ally of the United States, had put down its own communist insurgency by the late 1980s but remained concerned about its borders with Cambodia and Laos. Vietnam was occupying Cambodia after overthrowing the Khmer Rouge, and communist forces had taken control of Laos despite a horrific secret US bombing campaign there during the Vietnam War. Pichit, a Vietnam veteran with a fondness for boxing, wanted to replicate something similar to the Israeli settlements developed by the Fighting Pioneer Youth, known by the Hebrew acronym NAHAL. This paramilitary unit developed outposts that blended military service with agricultural work. Pichit envisioned duplicating this in Thailand and sought out Israeli diplomats in Bangkok for help.

In March 1987, 25 military and civilian officials from Thailand traveled to Israel for a two-week tour of moshavim and kibbutzim—two different kinds of planned communities—as well as settlements in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Golan Heights. It quickly became evident, however, that the frontier settlements envisioned by the Thai brass would never materialize. Why, exactly, isn’t totally clear, says Kaminer, who is writing a book on the subject. Israeli diplomats were skeptical of the plan from the beginning after earlier attempts to replicate the settlements in Myanmar and sub-Saharan Africa revealed the difficulty of exporting the model. Numerous groups of Thais, however, continued to travel to Israel in the following years, with the tours shifting to hands-on work, facilitated by Thai institutions and enterprising Israeli businessmen.

The experiments eventually served as a convenient method to import labor through a legal loophole. The Thais were classified as “trainees” or “volunteers” and paid an “allowance,” thereby bypassing restrictions on foreign labor and making it appear as though the visits were strictly educational. It was a mutually beneficial scheme, Kaminer explains, as both sides “had their interests in carrying through the charade.” The Thai government and private middlemen stood to gain through the infusion of remittances; the Israelis would get access to a pool of low-cost labor that wasn’t Palestinian. Thai workers were considered ideal because, as Kaminer observed firsthand while doing fieldwork among them, they did not trigger the “settlers’ exploitation anxiety.”

These initial Thai delegations coincided roughly with the start of the first intifada in late 1987. According to Israeli government statistics, in 1988, Palestinians held 25 percent of agricultural jobs in Israel and even more in its construction sector; many of these workers commuted from the West Bank and Gaza. After years of occupation, during which Israel had stifled development within the territories, many Palestinians had little choice but to look for employment in Israel. But in response to the intifada, Israel began subjecting Palestinian workers to onerous restrictions, harassment, and attacks. In turn, an active bloc of workers took to organizing, launching strikes and boycotts. When some resorted to violence, attacking and killing Israeli employers, Israel responded by further restricting Palestinian movement.

Then, in March 1993, more than two dozen Palestinians were killed by Israeli forces and settlers, and 15 Israelis were murdered, including the execution of two policemen, for which Hamas claimed responsibility. The Israeli government sealed off the West Bank and Gaza, confining millions of Palestinians in a sweeping act of collective punishment. Palestinians should not be allowed to “swarm among us,” Yitzhak Rabin, the prime minister at the time, said of his decision. Rabin added that he “would be very happy” to see fewer Palestinian workers in Israel. The move immediately created a vast labor shortage.

These problems were compounded by Israel’s unprecedented economic growth, which was occurring due in part to an immigration wave, creating an increased need for workers. Many of those immigrants were newly arrived Russian Jews who were often highly educated and had specialized skills and thus were not interested in low-wage, physically taxing jobs. While some temporarily took up construction or agriculture upon arriving in Israel, they quickly moved on to other occupations. Unemployment was high—around 11 percent—but the government was largely unsuccessful in its efforts to pressure out-of-work people into taking these jobs by withholding unemployment benefits.

The Israeli government initially opposed bringing in foreign workers, who at the time made up only 1.6 percent of the country’s labor force. Rabin cast the situation as a challenge that needed to be met collectively by society. “Can we get organized to withstand the absence of Palestinian labor with Jewish or other labor?” he asked in a 1993 address. Desperate for workers, the government even sent Israeli soldiers to harvest lilies and tulips for export.

None of this was enough, though, for the construction and agriculture industries, which were facing the prospect of unbuilt homes and fallow fields. They pressed the government for a long-term fix.

Just over a month after it closed off Gaza and the West Bank, Israel agreed to welcome more foreign workers into the country. The waves of workers brought in as part of Pichit’s quixotic settlement plans had, by 1993, made Thais a familiar, if still somewhat alien, presence to Israeli farmers. They were well-positioned to serve as cheap, easy replacements for the ousted Palestinian workers. Some 20,000 Thais arrived in Israel over the next few years, and others followed. Meanwhile, workers from Romania and Turkey started to fill jobs in the construction industry, and women from the Philippines traveled to Israel to provide home care and do domestic work.

By 1995, the proportion of Palestinians in the agricultural workforce had fallen to just 5 percent. That year, Rabin told a crowd at a fundraising event in Jerusalem that in four months, there would be no need for any Palestinian workers in Israel at all and that the “ultimate goal” was “separation between a Jewish state and the Palestinian entity.”

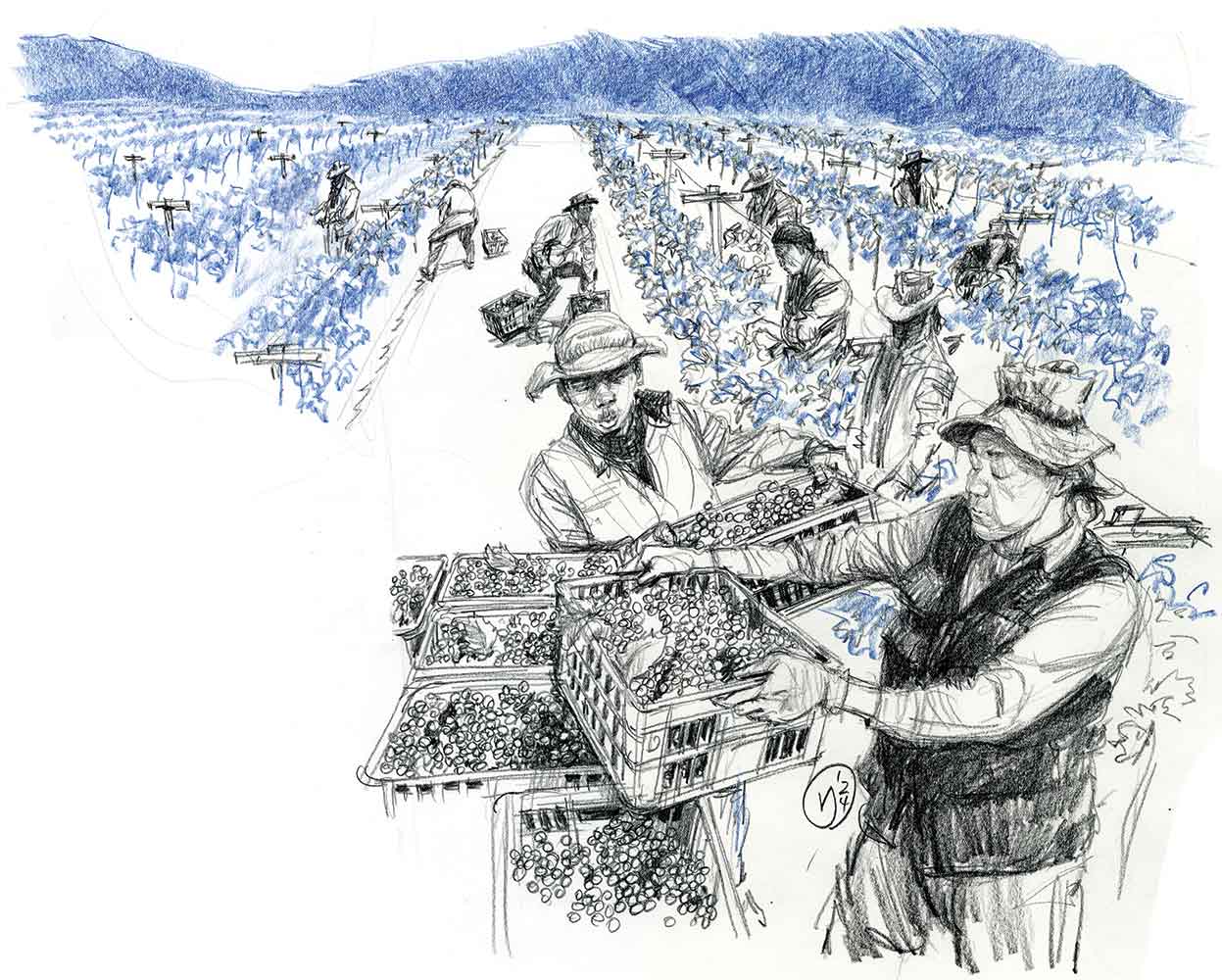

Before October 7, most of the 30,000 Thais in Israel were almost exclusively men working in agriculture, according to Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This was around three times the number of Palestinian agricultural laborers, says Assia Ladizhinskaya, a spokeswoman for Kav LaOved, an Israeli nonprofit that advocates for migrant workers.

Yet this large number of Thai workers (and Palestinians before them) labored largely out of sight—the better not to disturb Zionism’s long-standing back-to-the-land narrative, Kaminer says. “After all these years, and despite being completely contradicted by reality, there is this fantasy of Hebrew labor, of agriculture being carried out entirely by these pioneering, heroic Jewish settlers.” In reality, the typical worker picking vegetables and tilling fields in Israel looked more like Manee, a 29-year-old Buddhist man from Thailand’s northeastern Isaan region.

Home to about a third of Thailand’s population, Isaan is generally absent from the itinerary of the millions of foreign tourists who visit the country each year to indulge in the excesses of Bangkok and lounge on the Instagrammable beaches of the country’s south. It remains largely rural, with development lagging well behind the rest of Thailand. A 2022 report conducted by the World Bank found that poverty levels in the northeastern region of Thailand were almost double the national level.

Within Thailand, Isaan has long been stereotyped as a drought-prone backwater, its residents looked down upon as uneducated bumpkins. “In Bangkok,” the celebrated late author and Isaan native Kampoon Boontawee wrote in his novel A Child of the Northeast, “the very word ‘Isaan’ is almost a metaphor for poverty.” The economic conditions and lack of support from the government have long driven residents to seek livelihoods elsewhere. “Migration is a very inherent phenomenon for most of the families and people in Isaan,” says Shahar Shoham, a PhD student in global and area studies at Humboldt University of Berlin, who has conducted extensive field research in the region.

Manee’s family was one of many who took part in the generational cycle of migration out of Isaan. Before leaving for Israel, Manee had helped out around his village in Udon Thani province, lending a hand when others needed assistance with farming. But the pay was poor, so he decided to follow the path his father had taken about a decade earlier and then return home. His father had told him about the risks, but these were easily outweighed by Manee’s desire to make money. He generally enjoyed his time in Israel, where he worked as a gardener and maintenance man for nearly five years. Manee managed to send home about $5,700; not once did he splurge on a ticket to fly back.

Yet while there are better-paying jobs in Israel than in Isaan, the conditions are frequently exploitative and precarious. In December 2010, Thailand and Israel signed a bilateral agreement to shift oversight of the labor contracting process from private recruiters and subcontractors—who charged exorbitant fees to place Thais in jobs in Israel—to the respective governments. The agreement also created stricter enforcement mechanisms for labor regulations and programs to educate Thais about their rights. Recruitment fees plummeted as a result, allowing workers to pay off debt more quickly and begin saving income.

Despite this framework, however, and a new one that followed in 2020, labor activists and human rights groups have found that Thais working in Israel are regularly subjected to punishing conditions. In 2015, Human Rights Watch published a report documenting the widespread abuse of Thais working on moshavim by their employers, who illegally forced them to work long hours and live in squalid conditions. On one farm, the workers slept in cardboard boxes inside a shed. Other laborers said they had been treated “like slaves.” Five years later, data collected by Kav LaOved showed that 83 percent of migrant workers from Thailand were being paid less than the minimum wage. And in 2022, the US State Department said traffickers were subjecting Thais in Israel to forced labor by coercive measures such as withholding their passports. These difficulties are compounded for Thais who work in the fields near Gaza, which are often far from safe rooms and shelters and are not protected by the Iron Dome, Israel’s missile defense system. Thai laborers have been killed by rocket or mortar fire in 2004, 2010, 2014, and 2021.

As part of her research, Shoham collected and translated about 20 songs composed by bands made up of Thai workers in Israel. She hoped to better understand their experience working to support their families back home while enduring a foreign conflict to which they are not a party. In many of the songs, Shoham says, Thais sing of themselves as tough, selfless heroes from Isaan providing for their loved ones even as they are racked with feelings of fear and helplessness. “The Wrong Place,” written by a group of Thai laborers during the 2014 Gaza War, reflects such sentiments: “I am just a Thai worker / I came here to work and get paid. / Now I find myself in the wrong place, in the middle of the battlefield / Wondering, with tears and fear, if I will survive.”

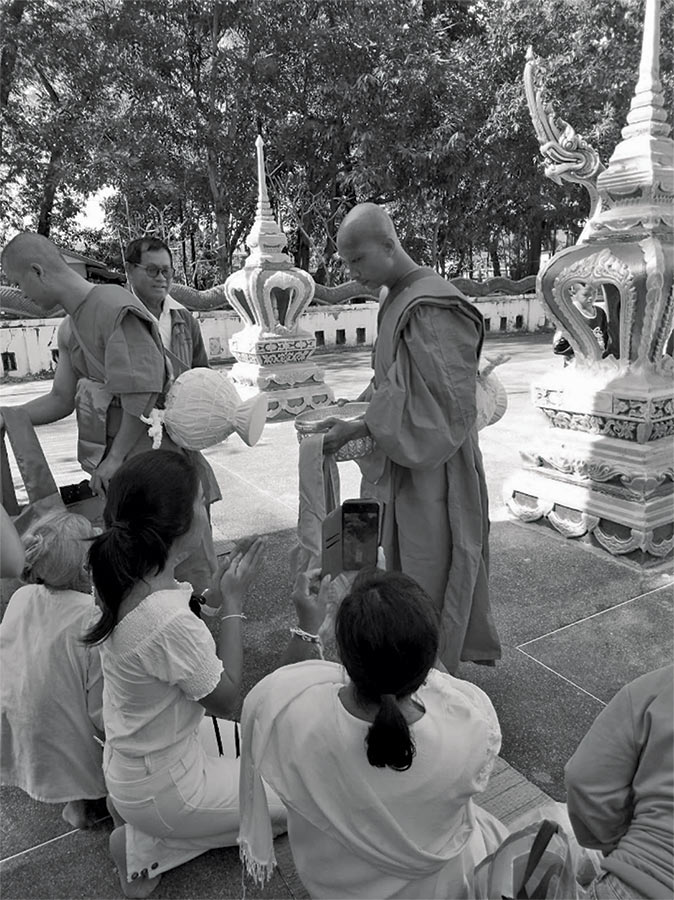

The day after the October 7 attacks, Chumporn Jirachat received welcome—if unsettling—proof that his son was still alive. The news, though, did not come from Manee, but rather from an image released by Hamas that showed Manee sitting cross-legged on a dirt floor with his hands behind his back. A Hamas fighter kneeled across from him, pointing an automatic weapon at his chest. Chumporn tried to keep his anxieties at bay by visiting shrines and temples to pray for his son’s safety. “This is the Thai way of soothing ourselves,” he says.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →After his abduction, Manee was taken into a tunnel along with other Thai hostages, berated, and hit. The workers told the Hamas fighters that they were Thai, but their captors didn’t seem to believe them. One struck Manee in the head with his gunstock. After three days, the hostages finally convinced the Hamas fighters that they were Thai workers. At that point, their captors became much less agitated and aggressive, Manee said, although the two young Israelis held with them continued to be verbally abused and screamed at.

A few guards kept watch over Manee and the rest of the captives. The guards said nothing other than that they would be released once the fighting ended. When the air became stagnant, the guards rigged up an electric fan. The food supply was inconsistent, Manee says. On some days, he subsisted on half a piece of bread and half a bottle of water. He found keeping track of the time while being held underground difficult, and the days blurred into each other. He lost track of how long he had been there.

Officials in Bangkok, meanwhile, were struggling to assess what had taken place. The casualty figures fluctuated wildly: At least one Thai laborer reported dead was actually alive, while the father of one of Manee’s murdered coworkers thought his son had been taken hostage. After an initial scramble, the Thai government evacuated nearly 7,500 people from Israel. Hundreds of others left on their own. Freeing the 31 Thais held hostage presented a more vexing task.

Thailand maintains diplomatic relations with Iran, which financially supports and backs Hamas. Following October 7, Thai lawmakers opened an informal channel with Hamas representatives and Iranian officials. An official diplomatic track began to take shape around the same time. When a temporary truce that halted the fighting in Gaza and Israel on November 24 allowed for an exchange of prisoners and hostages, a group of 10 Thai captives emerged from Gaza. More would soon follow. The agreement that led to their release was separate from the larger hostage and prisoner swap, the Thai Foreign Ministry said, and involved no conditions for the Thais’ release.

Manee was relieved when told of his impending release by his captors. Within a few days, he was blindfolded and marched out of the tunnel network. He returned to Thailand in late November and is still processing the horror of his captivity—and of seeing his good friend murdered in front of him. At the airport in Bangkok, he and the other returnees paused briefly, taking a moment of silence to honor their 39 countrymen who had been killed in recent weeks.

When The Nation spoke with Manee in February, he said that he was thinking of going to work abroad again—but not in Israel. Perhaps South Korea, where he might be able to land a job in a factory or restaurant or maybe on a farm. At the start of February, Manee was ordained as a Buddhist monk at a temple in his village. In doing so, he fulfilled a karmic bargain his father had made in the hope of his son’s safe return. “It’s like a rebirth,” Manee said. “I was given a second chance. I’m so grateful.”

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation