Why Trump Is Threatened by South Africa

The country’s Constitution gives its citizens more than a right to the pursuit of happiness. But attempts to redeem that commitment to justice have enraged American reactionaries.

South African farmer Tewie Wessels addresses a group of white South Africans supporting US President Donald Trump and tech billionaire Elon Musk during a demonstration in Pretoria, on February 15, 2025.(Marco Longari / AFP via Getty Images)

Cape Town—Last May, The Heritage Foundation called for the United States to cut aid to South Africa “until the country aligns with American values,” a claim repeated by Marco Rubio in his February announcement that he would not attend the coming G-20 this November, chaired for the first time in by an African country.

It’s easy to see that US attacks on South Africa, and Trump’s offer of refugee status to Afrikaners, are based on racist lies. All but a small group of far-right South Africans have treated the offer with derision, for the facts are well known to them. White people currently make up 8 percent of the population of the Republic of South Africa, yet hold 75 percent of the country’s wealth. Thanks to market liberalisation, their wealth actually grew after apartheid. Only a handful would trade living in a constitutional democracy where they have deep roots for a handout in Trump’s America. Trump’s fearmongering about black threats to white safety repeats apartheid-era propaganda, and betrays deep ignorance about South African history since 1990, when Nelson Mandela was freed, and the country as a whole began its long slow walk to freedom.

That history reveals why South Africa is a threat to Trump’s idea of America. which goes even deeper than racism. As banning, assassination, torture, and exile only increased resistance to apartheid, the regime responded brutally; peaceful transition seemed unimaginable. The story of creative intelligence, great leadership, fortitude, and eventual common sense that paved the way for a multiracial democracy has been told many times. But the transition left the country stuck in paradox.

South Africa has the world’s most progressive Constitution. Its core Constitution prohibits discrimination based on race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, color, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth. Even more significant are the social rights it guarantees: fair labor practices, a safe environment, housing, health care, food and water security, and education. All these are clearly and carefully specified, and they give every South African considerably more than a right to the pursuit of happiness.

Realizing those rights, however, would have required a transfer of wealth that would have doomed the peaceful transition most of the world thought impossible. The price of redistribution of political power was the preservation of economic power, leaving South Africa with one of the highest rates of inequality in the world. Decades after liberation, 30 percent of the population remains unemployed and living without basic services like electricity and water, next to gleaming cities where white and black entrepreneurs—and politicians—enjoy luxury estates. The gap between the ideals enshrined in the Constitution and the realities of life for most of South Africa’s citizens have led many to despair that the peaceful revolution that inspired the world has ground to a halt. That despair might sound familiar to the millions of Americans who sat out the last election. Why vote to defend a democracy whose benefits seem invisible?

A few days after Trump’s attack on South Africa, hundreds of South Africans gathered at the University of Cape Town to celebrate the 90th birthday of Albie Sachs, one of the drafters of the Constitution and a member of the first democratic constitutional court (1996–2009). Born to Jewish trade unionist parents, Sachs was jailed, tortured and banned during the apartheid years, eventually going into exile in England and Mozambique, where an attempted assassination left him with the loss of an arm and the sight of one eye. At 90, he still maintains a daunting schedule lecturing at home and abroad, but the conference, which I attended as a speaker, wasn’t only a matter of homage to the legendary social justice advocate. Most discussion was centered on probing and repairing the gaps between the Constitution and South Africa’s reality—which, many repeated, is still wracked by spatial apartheid.

What South Africans call spatial apartheid refers not merely to the divides between wealthy and poor neighborhoods taken for granted in cities across the world. Nor need one recall the dispossession of Indigenous lands that goes back to the Dutch settlements of the 17th century, or tell the story of the Bantustans—settlements whose Black residents were forcibly transported from elsewhere and imprisoned.

Spatial apartheid was intentionally constructed in living memory. Beginning in the 1960s, laws forbidding black people to live in the central parts of cities were violently enforced. Vibrant mixed neighborhoods like Cape Town’s District 6 or Johannesburg’s Sophiatown were razed and their inhabitants, allowed to take just one suitcase for their belongings, were resettled in squalid townships far from the city center, which still lack. In recent years, toddlers have drowned in open sewage in Khayelitscha, not far from Cape Town’s splendid high-end waterfront—some of it built on landfill extended with the rubble of demolished homes in District 6.

The expropriation bill that aroused Trump’s ire simply specifies the terms in which land may be taken for public use—for example, to provide decent housing for those communities that were driven off their land without compensation. Any such restitution must take place according to complex legal proceedings, as Pierre de Vos, the University of Cape Town law professor who organized the conference, detailed. That complexity is one reason why no public housing has been built in Cape Town since 1994, despite endless court victories and promises.

Black and white South African lawyers, architects, and activists are working to close the gap between the democratic legal mechanisms established after apartheid, and the grinding inequality that threatens to undermine democracy itself. One NGO focuses on the fight for social housing in publicly owned upmarket areas in Cape Town. Ndifuma Ukwazi—“Dare to know” in Xhosa—has mapped Cape Town to determine 128 square kilometres of underused public land. The size of Barcelona, it’s more than enough to house the millions of people stuck in Langa or Khayelitscha, whose self-constructed shacks are not only painfully inadequate but far from decent jobs. Unemployed older men sit vacantly in scrubby patches of shade. Is it surprising that younger ones turn to violence? As Justice Sachs told me, homelessness goes deeper than the absence of physical protection: home is a human right because it’s the source of security, dignity, and moral citizenship.

Housing activists, supported by Ndifuma Ukwazi’s legal team, have occupied unused buildings and demanded that the city build public housing on tracts now serving, for example, as lush golf courses or left undeveloped for future speculation in Cape Town’s lucrative property market. All this could be done without expropriating an inch of private property. But precisely because the legal safeguards are so tightly bound, initiatives have languished. Mpho Rameone, the NGO’s executive director, sees international patterns. In Cape Town, spatial injustice was intentionally created by the apartheid government. Elsewhere, she told me, market fundamentalism does the same work, pushing the nurses and policemen, teachers and artisans whose work keeps cities running out of their centers.

Former president Jacob Zuma is often compared to Trump, both for his casual use of state funds to fill his pockets and for his penchant for petty revenge. Under his tenure, the state actively stalled attempts to fulfill its constitutional obligations. His presidency is sometimes called the nine wasted years (2009–18). In passing the expropriation bill, President Cyril Ramaphosa hoped to make good on the peaceful revolution’s promise.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Since the 2024 elections brought a national unity government to power, many South Africans are hopeful again. Their Constitution includes all the social rights formulated in the 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights, which was ratified by most nations but realized by none. Though spearheaded by Eleanor Roosevelt and signed by the United States, it has gained little traction with Americans, for whom healthcare, housing, education and fair labor practices are not rights but benefits—to be given or denied at the will of an employer or a state government. The spatial injustice that thoughtful South Africans are working to redress is an entirely foreign concept to those California cities that have criminalized not only homelessness but even the act of aiding and abetting the homeless.

Were South Africans to succeed in using their Constitution’s strong commitment to political rights to realize social rights, it would inspire many others, for it indeed poses opposition to American values; Ramaphosa urged his citizens to stand “against a harsh global wind.” As of this writing, he is the world’s only head of state to offer an eloquent answer to Trump. His State of the Nation address did not mention the American president by name, but declared that the nation was too resilient to be bullied, and listed its core values:

As South Africans, we stand for peace and justice, for equality and solidarity. We stand for non-racialism and democracy, for tolerance and compassion. We stand for equal rights for women, for persons with disability and for members of the LGBTQI+ community. We stand for our shared humanity, not for the survival of the fittest.

Since that speech, South Africa has been under further diplomatic attack. Who’s surprised that America’s property developer in chief would take umbrage at the idea that property rights are not absolute—that a home might take precedence over a golf course? European diplomats support South Africa’s position, though, as is the wont of European diplomats, they have done so quietly.

“We are waiting to hear something from the Americans,” one told me. Vanessa September, a South African architect and urbanist, spoke to me more bluntly. “It would be comforting to hear more American voices distancing themselves loudly and clearly from the totally misinformed attacks on our country.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day

We may already be on a superhighway to the sort of class- and race-stratified autocracy that it took Russia so many years to become after the Soviet Union collapsed.

Israel Wants to Destroy My Family's Way of Life. We'll Never Give In. Israel Wants to Destroy My Family's Way of Life. We'll Never Give In.

My family's olive trees have stood in Gaza for decades. Despite genocide, drought, pollution, toxic mines, uprooting, bulldozing, and burning, they're still here—and so are we.

Trump’s National Security Strategy and the Big Con Trump’s National Security Strategy and the Big Con

Sense, nonsense, and lunacy.

Does Russian Feminism Have a Future? Does Russian Feminism Have a Future?

A Russian feminist reflects on Julia Ioffe’s history of modern Russia.

Ukraine’s War on Its Unions Ukraine’s War on Its Unions

Since the start of the war, the Ukrainian government has been cracking down harder on unions and workers’ rights. But slowly, the public mood is shifting.

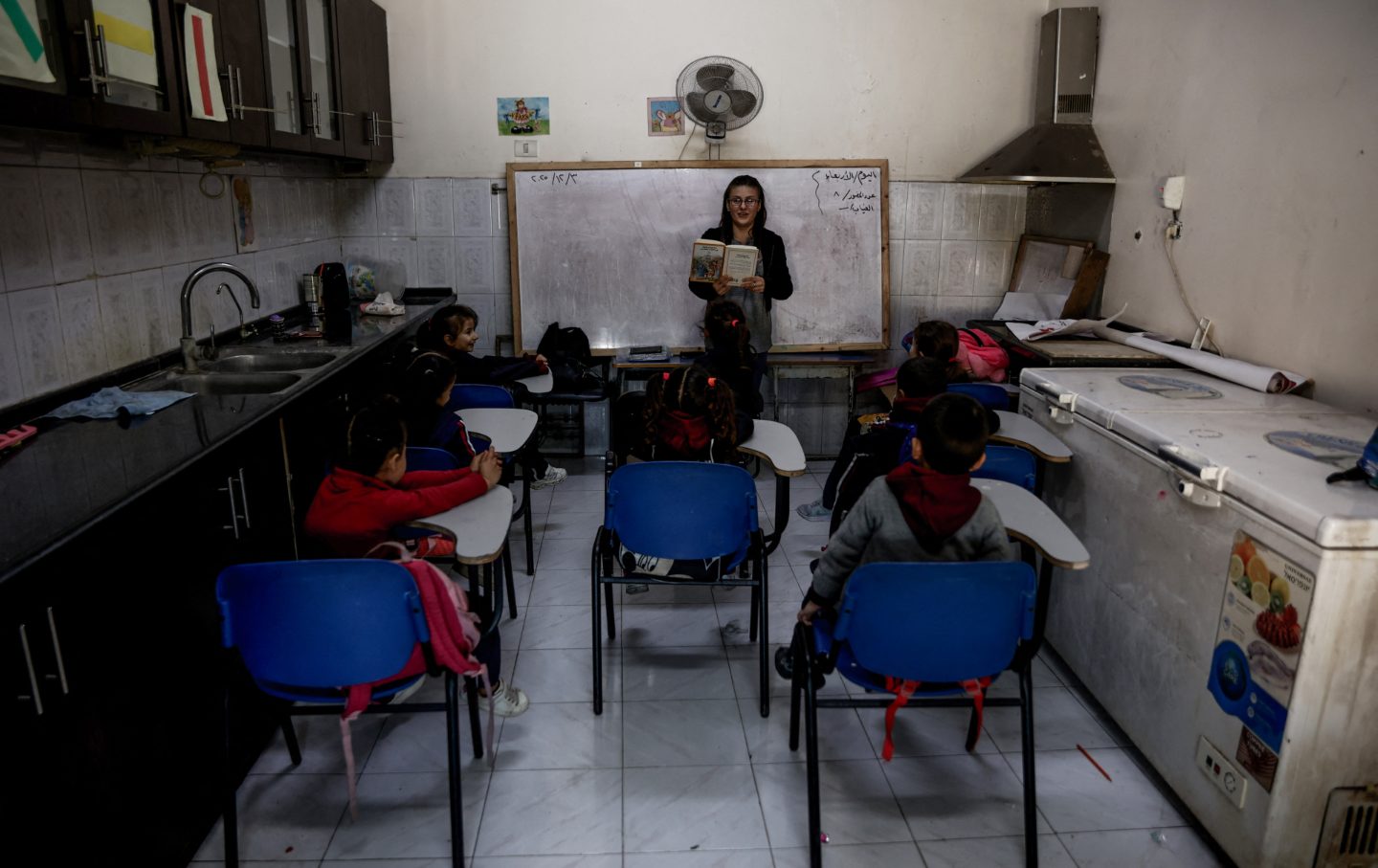

I’m a Teacher in Gaza. My Students Are Barely Hanging On. I’m a Teacher in Gaza. My Students Are Barely Hanging On.

Between grief, trauma, and years spent away from school, the children I teach are facing enormous challenges.