Istanbul—At just after 4:17 am on February 6, nature made a lethal intervention in Turkish history.

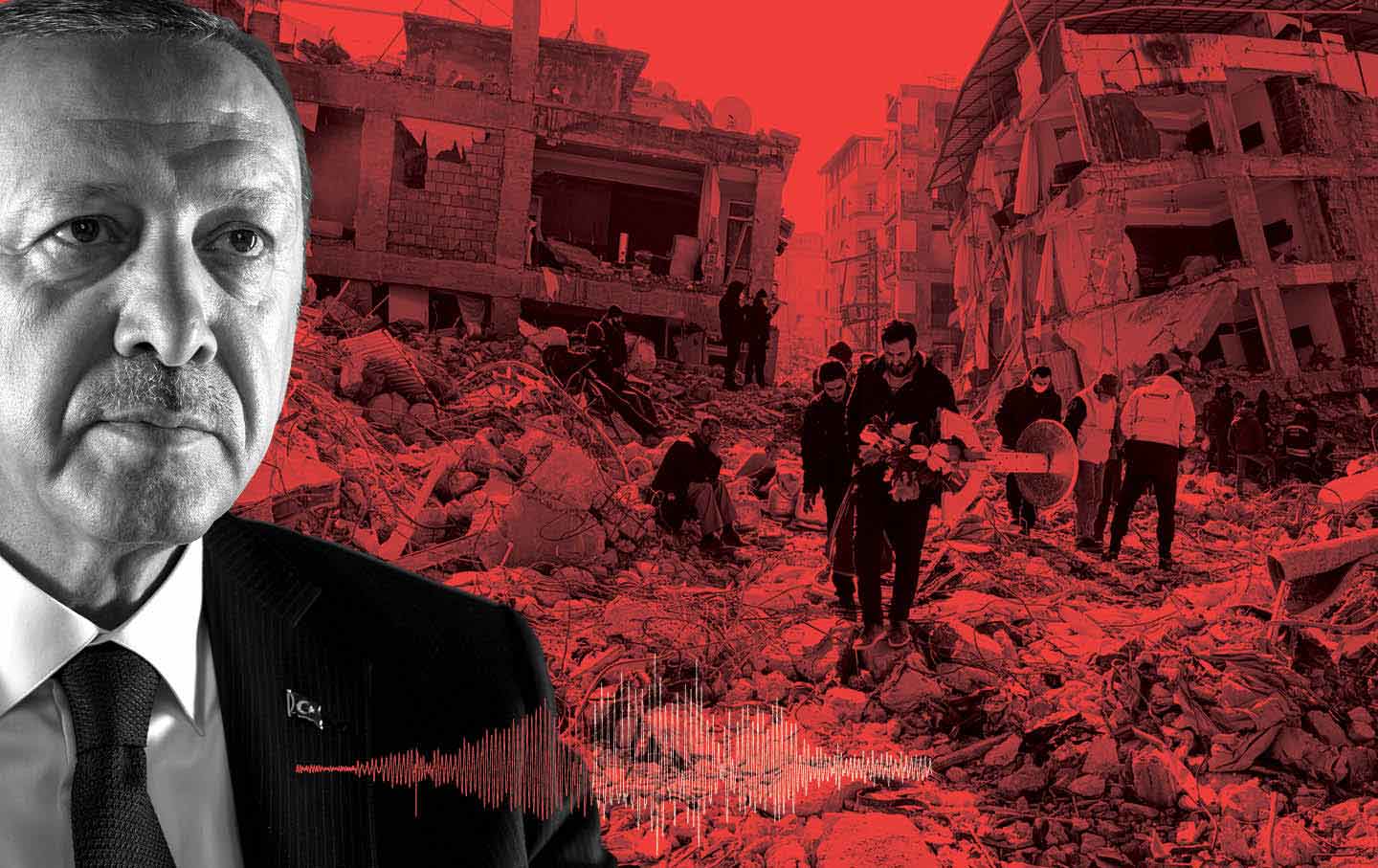

At first I wasn’t aware of the scale of the destruction. Here in Istanbul, we felt nothing—just an eerie silence in the morning, the final serene moments of unknowing. But my aunt, who woke up in horror in her bed in Gaziantep, the epicenter of the 7.8-magnitude earthquake, called me just a few hours later. What she told me I found hard to imagine. Then, just after 1 am, I turned on the TV. A reporter was running in panic as massive buildings on both sides of the road began collapsing in a new, 7.6-magnitude quake. I saw rectangular forms, each containing perhaps dozens of people, merge into one another, throwing out enormous clouds of white dust, the occupants letting out horrifying wails. I saw terrorized men and women, unsure of what to do, summoning Allah for help. Deep inside, I felt something rising: my stomach turning in disgust and my heart racing. On a live broadcast, in real time, I was witnessing the drawing back of the curtain from Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s regime, the complete meltdown of his “New Turkey”—whose price 50,000 citizens were now paying with their lives.

I’ve written several profiles of Turkey’s president over the past decade, often framing him as a figure of strength. While leftists like me might criticize his projects—and their harmful environmental impacts—Erdoğan retained his reputation as a doer. It was he who built the roads; he who commissioned new airports. His authority made sure Turks could continue to purchase an endless supply of new housing. We in the opposition, meanwhile, were just talking. He denounced us for sabotaging his entrepreneurial spirit and undermining Turkey’s prosperity. Now, as the geological fault lines shifted with catastrophic impact and tremors on a scale not seen for half a millennium shook southern Turkey, I realized with epiphanic clarity that Erdoğan wasn’t so strong after all. If lasting deeds were the measure, he wasn’t even a doer; he was just another talker. The legacy of his Justice and Development Party, the AKP, built over all those years, was revealed as shoddy construction and unsafe buildings—nothing more. Twenty years of continuous bragging about the monumental feats of his Islamist reign were reduced to rubble in the course of a bleak February day. By midnight, I was feeling violated, seeing for the first time how we had been hoodwinked for more than two decades by a rhetorical trick. Everyone watching those scenes of endless ruined streets, pancaked buildings, and desperate citizens must have felt something similar, I thought that night before falling into bed. The collapse of southern Turkey, I told myself, would surely mark the fall of Erdoğan.

The reckoning began the next morning. Hadn’t scientists been anticipating this quake for years, pinpointing its probable location just three days before? Why did Turkey’s president ignore them? Why did he imprison the urban planners and architects who criticized the eight successive “construction amnesties” for illegal building that the AKP kept issuing in exchange for votes since rising to power in 2002, instead of listening to them? Why did he appoint İsmail Palakoğlu—a theologian with no experience in humanitarian rescue—as the head of disaster response for Turkey’s official rescue agency, AFAD? Why did AFAD ban independent rescue missions and block private donations, turning back thousands of volunteers who tried to reach the impacted areas while insisting that all aid must be dispensed by “the Chief” (Erdoğan’s moniker) in Ankara? By the time I started taking notes, such questions were already piling up—as were my own feelings of anger, frustration, and even regret. When did we Turks begin believing this man and his party? How could Erdoğan’s rhetoric have blinded us to the fact that his entire regime was built on unstable ground?

“It’s all part of fate’s plan” was the pious Erdoğan’s initial explanation for the calamity. My friends and I couldn’t believe our ears; we responded by organizing street marches, shouting, “Government, resign!” At football matches all over the country, thousands of fans chanted the same slogan. But nothing happened. Not a single official resigned. Instead, Erdoğan asked for the “blessing” of Turkey’s citizens as an estimated 200,000 bodies still lay buried under rubble.

I couldn’t help recalling the central insight from scholar Amartya Sen’s study of famine in India: Centralized autocracies (like India under the British Raj—or Turkey under Erdoğan) tend to exacerbate the human toll of natural disasters. Had Turkey actually been a democracy, the free flow of information would have helped shape the state’s response to the disaster. Instead, our autocratic rulers merely watched while Turkey’s citizens died in the thousands.

And by the middle of February, much to my dismay, Erdoğan was already attempting to turn the “Disaster of the Century” into an opportunity. He hired an agency to produce a short film with that title (its central theme: No government could have effectively handled a crisis of such magnitude) and instructed all state-controlled media to refer to the quake using that expression. He pledged to quickly rebuild the 11 cities that had been leveled. “Just give me one year,” he stated.

But Erdoğan’s plan to use Turkey’s public housing agency, TOKİ, for this task poses a huge financial and logistical challenge for his crumbling regime. Last October, inflation hit a 24-year high of 85.5 percent; in March, the Ministry of Treasury and Finance calculated the damage caused by the quake at $103.6 billion. New public spending at anything close to that scale risked sending inflation even further out of control, pushing the cost of basic necessities even higher at a time when the country’s unemployment rate—a dangerous 10 percent—meant that Turks already felt squeezed.

As the days passed, the behavior of Erdoğan and his far-right coalition partner, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), was becoming increasingly erratic. In despair, I started smoking cigarettes again—a habit I’d quit a decade before—and watched as Erdoğan condoned the behavior of the MHP’s leader, Devlet Bahçeli, who turned away survivors of a collapsed 12-story building when they asked to use the toilet facilities on his estate in Osmaniye. The US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, visited the quake site before Bahçeli, who, when he finally did arrive, was filmed shouting and gesturing at quake survivors who were protesting government inaction.

On February 11, one far-right quake survivor from Hatay Province, near Syria, complained to a reporter with Deutsche Welle’s Turkish Service that the breast-thumping Turkish nationalists he adored were absent during the earthquake’s aftermath, while those he considered “traitors”—the communists and the Kurds—rushed to his rescue. “Our house is in ruins. I’m an MHP voter. I haven’t seen anything done by the MHP. They didn’t give us even a loaf of bread. Who looked after us? The terrorist organizations did; they did look after us,” he said. The French government also came to the rescue, as did the British, countering the xenophobia promoted by Erdoğan’s regime simply by being there and bringing sandwiches. The more I encountered these fragments of New Turkey’s collapse—on the streets and in my Twitter stream—the more I felt compelled to reexamine Erdoğan’s project, to understand how he had shaped me, and my country, and how we had reached this point.

Helpless in Hatay: In this southern Turkish city, people wait for news of their loved ones, trapped benath the rubble.(Burak Kara / Getty Images)

What was the AKP? Against whom did Erdoğan position himself as the symbol of strength in Turkish politics? Cihan Tuğal, a professor at UC Berkeley, wrote one of the best books on this subject. In The Fall of the Turkish Model (2015), Tuğal describes the AKP’s ideology in two words: “Islamic liberalism.” Erdoğan’s movement wedded free-market capitalism, conservative Islam, and parliamentary democracy in what seemed like a winning formula for Middle Eastern countries in the early years of the 21st century. In the mournful days after the quake, reading Tuğal’s book, I remembered my excitement as a young writer in the mid-2000s, when foreign capital poured into Turkey, making the Turkish lira equal to the dollar and opening new horizons for the aspirational. I got my first office job, as an arts reporter for Newsweek’s Turkish edition, before moving to Rolling Stone Türkiye. In those years, I was among the many who considered the “Old Turkey”—before the AKP’s rise—to be a regime in intensive care. Isolated from the West, reveling in its past glories, it was breathing its last before our eyes. Few of us mourned when Erdoğan’s New Turkey replaced it with a promise to bring the country into the European Union.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

Like many other Ottomans, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who founded modern Turkey in the 1920s, was deeply influenced by the French Revolution. Soon after the storming of the Bastille, Tuğal writes, “Istanbul and other Ottoman cities were decorated with French flags.” The triumphant Kemalists saw parallels between their militantly secularist revolution and the anticlericalism of 1789. But by the 1970s, the Kemalist model was facing a crisis, with Islamism on the rise as a response to Turkey’s succession of secularist dictatorships—particularly during the terrifying aftermath of 1979’s Iranian Revolution. The French model was both the strength and the weakness of the Old Turkey: “Turkishness” was a sacred concept, as was secularism, the nation-state, and the cult of personality constructed around Atatürk. Fashioning myself as a young New Left thinker, I learned about the Armenian genocide, the oppression of the Kurds, and other dark spots of Turkish history that the Kemalists refused to acknowledge—and I saw that I would get into trouble if I wrote about them.

When the AKP emerged in 2001, it seemed to represent a counter to Iran’s anti-Western stance and to diminish the appeal of terrorist organizations like Al Qaeda by offering a moderate, capitalism-compatible Islam. The AKP’s liberal model was empowered by the so-called “Islamic Calvinists”—the millions of pious people in Anatolia who favored capitalism in this former seat of the Islamic caliphate. This moderate Islamic movement was especially attractive in the aftermath of 9/11, as it promised close engagement with the United States throughout the War on Terror. Besides de-radicalizing Islamists, Erdoğan’s New Turkey also delivered a robust economic program that soon reduced the country’s chronic inflation—which had hit 105 percent in 1994—to single digits.

The AKP, in its first decade, was good for capital—both locally and globally—so captains of industry wholeheartedly supported it. The party worked with the IMF to privatize natural resources and public enterprises, which in turn helped attract foreign direct investment. Bolstered by the support of global capital, the AKP sold off forests and other public lands. Turkish society’s top 1 percent controlled 39.4 percent of the country’s wealth in the late 1990s; by the late 2010s, it controlled 54.3 percent. This deepening of inequality was achieved by depressing wages, curtailing unions, and limiting strikes.

“When I talk to my rich relatives in Istanbul, who hate Erdoğan so much, I ask why they complain about him at all,” Halil Karaveli, the author of Why Turkey Is Authoritarian (2018), told me. “Turkey’s wealthy had never been wealthier than they were under the first decade of Erdoğan’s reign.” Yet right from the start, there was a cultural incompatibility between Turkey’s mostly secular industrialists and the leader of an Islamist party who’d grown up working as a street peddler in a poor neighborhood in Istanbul.

By the early 2010s, Erdoğan’s regime had made progress in creating its own bourgeois class. These new allies all belonged to the construction sector. The biggest of Erdoğan’s new cronies—later named the “Gang of Five”—won contracts for all of his pet projects: a new intercontinental bridge spanning the Dardanelles; the world’s biggest airport, in Istanbul; housing projects in Anatolian cities; new highways, and smaller airports, linking Turkey’s distant corners to its capital, Ankara. Those who benefited from the AKP’s rise turned a blind eye to how brutal their allies were in oppressing Turkey’s working classes—even more than their secularist predecessors had been. Erdoğan’s culture war against the “secular elites,” we quickly learned, was just a pretext to empower his favored Islamist industrialists against their competitors.

By 2013, the West’s admiration for the Turkish model seemed to have gone to Erdoğan’s head, accelerating his transformation into a strongman. In speeches expounding on “Neo-Ottomanism”—his grandiose vision of an expansionist Turkey eager to become a regional superpower—he frequently raised his fist, accusing his enemies of wanting to “bring Turkey to its knees.” He began decorating Istanbul with tulips to commemorate the Tulip Era of the 1720s—a prosperous period in Ottoman history during which the tulip became a symbol of luxury. That era, however, had ended with a violent rebellion in 1730, organized by an ex-janissary (a member of the sultan’s elite guard) named Patrona Halil, whose followers pillaged Ottoman palaces.

Behind the glossy facade of Erdoğan’s regime lurked something similar. In 2013, the rate of construction workers dying on the job was nearly four per day as Erdoğan’s Gang of Five devoured new building contracts. Meanwhile, worries about environmental destruction and building safety standards were reaching a peak. (The number of worker deaths would continue to rise over the next decade: In January of this year, 119 died on the job; in February, 182 died.)

Park life: The protests against government plans to pave Gezi Park in 2013 were the first serious stirrings of opposition to Erdogan’s regime.(NurPhoto / Corbis via Getty Images)

One day in May 2013, I was walking through Gezi, a large public park in Istanbul, on the way to Cihangir, a rundown neighborhood popular among Turkey’s leftists, artists, journalists, and LGBTQI communities, when I witnessed a strange scene. Sırrı Süreyya Önder, a socialist MP and film director (we wrote for the same leftist newspaper, Radikal), was standing between a tree and a bulldozer. Surrounded by cameras, he was trying to stop the felling of trees to make way for a kitschy shopping mall that Erdoğan wanted built in the park. This incident was the spark that kindled the uprising later known as Occupy Gezi.

I spent the next few months in an atmosphere that, so I imagined, resembled Paris in 1871: As thousands of people with tents converged on the park, Gezi became a commune for those who opposed the government’s “redevelopment” plans. In those ecstatic, violent days, millions marched in Turkish cities against the AKP’s project of Islamic liberalism, and the park became a battleground between activists, who wore goggles and carried lemons (to counter the effects of tear gas), and heavily armored cops. The uprising was made up mostly of young activists—but it was led by seasoned urban planners, architects, NGO leaders, and lawyers who opposed the AKP’s politics of unbridled development and unregulated construction. But theirs was an uphill battle: A constitutional referendum in 2010 had allowed the government to appoint members of the Council of Judges and Prosecutors (the national council of the Turkish judiciary) and the Constitutional Court, which helped the AKP consolidate its control over the judiciary and use the courts to ratify Erdoğan’s rule. Last year, a court sentenced a number of the Occupy Gezi leaders to jail: Urban planners Mücella Yapıcı and Tayfun Kahraman and lawyer Can Atalay are now serving 18-year sentences for “attempting to overthrow the government.” Amnesty International’s “Free the Gezi 7” campaign has so far not succeeded, but Gezi’s legacy lives on: The uprising opened our eyes to a new horizon of possibilities for this country.

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

If the February 6 quake—in which thousands of illegally and shoddily constructed buildings became tombs for their inhabitants—vindicated the environmentalism of the Gezi activists, it also proved that our fears about Erdoğan’s authoritarian ambitions were well-founded. The AKP’s construction regime had been based on crony capitalism and organized greed masked by piety—just as we had shouted from the rooftops for weeks. Yet the Gezi rebellion wasn’t popular among the Turkish electorate. In the March 2014 local elections—the first held after Gezi—Erdoğan’s party increased its share of the vote from 38.8 percent in the previous election to 42.8 percent. In August 2014, he won the presidency with an outright majority of 51.8 percent following a campaign that branded Gezi protesters as enemies of the New Turkey. In a sense, the Gezi protests rescued Erdoğan by giving him a new framing: He was the hero—and we were the villains. The extreme right adored his rhetoric of absolute power and relished watching his regime crush “traitors.” His campaign slogan, “The Strong Will,” summed up his new politics in contrast to “the vandals of Gezi.”

By forming an alliance with Bahçeli, the leader of Turkey’s extreme right, Erdoğan had seemingly become all-powerful. He had a free hand to assault Turkey’s Kurdish and Alevi populations. Claiming to represent “the strong will” of the majority, he went after the LGBTQI communities (banning Pride marches in 2015, the year after he became president), Marxists, and even liberals (the Open Society Foundation ceased its Turkish operations in 2018 after Erdoğan waged war on “the famous Hungarian Jew, Soros”), denouncing them as Turkey’s “internal enemies.” In 2017, he initiated a constitutional change that destroyed Turkey’s parliamentary order—one that dated back to 1877 and the opening of the first Ottoman parliament—turning Turkey into a Latin American–style presidencialismo.

I remember the period between 2017 and 2019 as years of horror in Turkey. Erdoğan’s regime detained 332,000 citizens, arrested 19,000, and closed down newspapers, while keeping the country in a constant state of emergency. I had naively believed that the AKP’s liberalization of Turkey would help journalists like me reach a wider European and even American audience—every writer’s dream in the mid-2000s. With Radikal, the newspaper I’d been writing for, closed and my editor friends locked up in Silivri, Europe’s largest prison, I switched to writing in English and spent my days chronicling Erdoğan’s authoritarianism for European and American readers. In 2019, the Turkish government arbitrarily removed legally elected mayors from three cities, five provinces, and 45 districts because they were from the progressive People’s Democratic Party (HDP) and replaced them with loyal placeholders. The same year, it annulled the results of the mayoral election in Istanbul after the candidate of the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) defeated Erdoğan’s man—who then lost the new election by an even larger margin.

During his 20-year reign, Erdoğan has repeatedly seized on crises to rally support. Following a coup attempt against him in 2016, he called the insurrection a “gift from Allah” and used it to justify his purge of the public sector. When Erdoğan canceled the 2019 elections, his operatives claimed that “something had happened”—implying a mysterious conspiracy against the government. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Erdoğan announced curfews, closed mosques, and created a false sense of security by having his health minister brief the public each evening, fostering the illusion that everything was under control. Yet while I was reporting on his regime’s Covid-19 response, I saw how the state had failed to provide vaccines months after they were available in European countries, didn’t distribute masks in the first year of the pandemic, and concealed the number of Covid deaths. (The Turkish Statistical Institute recently revealed that the number of excess deaths for 2020 and 2021 together was 201,650; the Health Ministry had reported just 82,361 Covid deaths for those years.) Despite all these obvious failings, and thanks to the bombastic rhetoric disseminated by pro-government newspapers and networks (which represent 90 percent of Turkish media), people continued to believe the myth of Erdoğan, the strong leader.

In over his head: Ismail Palakoglu, a theologian with no experience in humanitarian aid, was appointed head of disaster relief.

“The same inadequacy we’ve seen during the pandemic has resurfaced with the quake,” said Edgar Şar, a cofounder of the Istanbul Political Research Institute. “There was a moral vacuum for the government when people saw how it couldn’t reach earthquake sites in the first 48 hours and refrained from mobilizing the military. All that affected the fault lines of society.” Şar, who lost relatives in the quake and was visibly traumatized during our interview after spending days working in the rescue operation in Hatay, predicted that the earthquake would be “a breaking point” for the government and will be remembered in the future “as the event that closed this era and put the last nail in the coffin of Erdoğan’s regime.”

Turkey’s opposition alliance was already close to winning the election before the earthquake, according to Şar’s research. “For the opposition, the vital issue before the quake was whether they would make a major mistake, like nominating a candidate all its parties didn’t fully support,” Şar said. On March 6, the alliance settled on a winning formula: Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of the CHP, the main opposition party, will run as a presidential candidate on May 14, with the extremely popular mayors of Istanbul and Ankara, Ekrem İmamoğlu and Mansur Yavaş, on the ticket as his vice presidents. The pro-Kurdish HDP and other small leftist parties will also support his candidacy. Kılıçdaroğlu has made reconciliation with Turkey’s pious masses the central tenet of his secularist party’s post-Gezi platform. He has also assembled a coalition made up of politicians that pious Muslims have been supporting for years. In fact, Kılıçdaroğlu’s two closest allies had until recently both functioned as Erdoğan’s wingmen: the former AKP economy czar Ali Babacan and the former AKP prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu.

Which brings us to May 14, 2023. The general election on that day will decide Erdoğan’s fate. In reporting the story of Turkey over the past decade, I’ve always urged caution about the possibility of change: As I’ve noted, Erdoğan’s rhetoric of the strong leader has repeatedly triumphed at the ballot box. But February 6 may have finally put paid to that. The date of the election, which Erdoğan chose himself, is itself symbolic, marking the anniversary of the 1950 landslide victory of the Democrat Party—a coalition of disgruntled conservatives, liberals, and leftists that ended the three-decade reign of the CHP, in the first free elections in Turkey’s history. For years, Erdoğan positioned the AKP as a modern-day iteration of the Democrat Party and has characterized the CHP as “the symbol of autocracy.” There is considerable—and perhaps intentional—irony in this. Erdoğan still seems blind to the nature of his single-party regime, whose corrupt grip on power assigns to the modern-day CHP (Turkey’s oldest political party, founded by Atatürk) a role similar to the Democrat Party’s in 1950: that of a disrupter of autocracy. Yet the symbolism of dates doesn’t end there. If this year’s election goes to a second round, it will be held on May 28—the 10th anniversary of the Occupy Gezi protests.

I spent March fretting about Erdoğan’s electoral strategy. After voicing their fury about construction standards and the government’s inadequate response, most people recognize that the quake survivors still need houses to live in. Erdoğan knows this. The Turkish right has successfully employed an “only we can build” strategy since the 1950s, when the Democrat Party came to power. Süleyman Demirel, the long-serving leader of the center-right party that ruled Turkey for years before the AKP came to power, was known as the “King of Dams.” Turgut Özal, the leader of liberal Islamists in the 1980s and an idol of Erdoğan’s, was the “Prince of Highways.” Erdoğan himself earned the moniker the “King of Airports and Bridges” and often boasts of his “crazy projects,” which include a sea-level waterway connecting the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara—bisecting Istanbul’s European shore to form an island between Asia and Europe. Murat Kurum, Erdoğan’s minister of the environment, urbanization, and climate change, announced on March 5 that construction had begun on 349 new apartment buildings for the survivors and that 608 more would follow soon. At the same time, by arresting more than 100 property developers responsible for the collapsed buildings, the regime has attempted to deflect attention and hide its responsibility.

But the quake exposed the rot beneath the shiny surface of Erdoğan’s reign. His New Turkey was literally built on the construction and housing industries, whose shoddy and unsafe products, enabled by the regime’s pervasive corruption, now lie in ruins. Erdoğan’s last construction amnesty—which legalized unlicensed structures in return for paying a fee and filling out a form—took place in 2018. Seven million buildings benefited from it. Pelin Pınar Giritlioğlu, the president of the Istanbul branch of the Union of Chambers of Engineers and Urban Planners, told the BBC that up to 75,000 buildings in the area affected by the earthquake had received Erdoğan’s “amnesties.” (Erdoğan then abruptly shelved plans for a new amnesty planned for this year’s elections.)

Researching the destroyed buildings, I was struck by the common practice of reducing the number of load-bearing columns in the shops on the entrance floors of residential buildings. Data released in 2020 by the Environment and Urban Ministry shows that about half the buildings in Turkey were built in violation of seismic regulations. I was also struck by the demography of the region. The cities most affected by the quake—Adıyaman, Malatya, Maras, Gaziantep, and Urfa—are all Erdoğan strongholds, and in my interviews with locals, they sent a unified message: We were forsaken; nobody came to our rescue; the supposedly powerful state didn’t even pitch a tent or bring a mobile toilet for us. Erdoğan’s new focus on reconstruction is designed to divert attention from the lethal failures of his rescue agency and the role of the big construction companies that funded the AKP and were responsible for the wreckage. This makes it all the more important that we refuse to be distracted.

Bathroom blocker: Nationalist leader Devlet Bahceli, who refused to let quake victims use the toilets on his estate in Osmaniye.(Duvar English)

It seems clear that Erdoğan will try to use the disaster as a lifeline. But Halil Karaveli describes the earthquake as potentially “the Chernobyl moment of Turkey. Just as the nuclear disaster was the final straw that destroyed trust in the Soviet system, this quake might destroy trust in New Turkey.”

For now, the disaster seems to have tipped the balance in the opposition’s favor. “People long identified the government with construction and highway projects, which both imploded during the earthquake,” Şar said. “This quake revealed how rotten the AKP’s system had been—and how it resembled a badly built house.” In this way, it has provided the opposition with a historic opportunity.

Dimitar Bechev, a lecturer at Oxford University, agreed that the earthquake would make it more difficult for Erdoğan to cling to power. As a result, Bechev said, “he may switch from buying electoral support through generous handouts to rigging the vote and repressions against the opposition bloc. In such a case, Turkey could become even more authoritarian because of the ratcheting-up effect, with repression leading to more repression rather than a loosening of the regime. Still, for the time being, Erdoğan’s preference seems to be using reconstruction to rally society behind the flag. Plan A is, he uses money—not jail sentences—to prevail.”

Yet Plan B remains a worrying possibility. After all, jail sentences are a tactic as common as bribery for the AKP. In the run-up to the elections, Erdoğan dispatched security forces to raid the solidarity tents pitched by opposition parties, confiscating their equipment, threatening volunteers with imprisonment, and appointing “trustees” to run them. For a leader who banned Twitter three days after the quake—making it impossible for people still under the rubble to tweet their addresses to rescue teams—there are no longer any red lines that can’t be crossed.

“Oppression will definitely accelerate in the run-up to the elections,” Şar predicted. “The earthquake brought the moment of the AKP’s collapse forward in time, and it also impacted it with a new magnitude. The government’s oppression will increase with the same magnitude. Yet we have elections soon, and none of those oppressive measures will help the government get more votes. There is a chance they’ll backfire.”

With the corruption so vividly exposed, and with a unified opposition, there is a good chance that Turkey’s anger will turn into an electoral victory for the opposition later this month. Weakness is something you can’t unsee. Watching Erdoğan as he visited the disaster site in February, I was among the millions who noticed the shaken expression on his face. Voters will soon decide whether this fixture of Turkish politics for three decades has outstayed his welcome. The resentment that has been building for years, and is now represented by an opposition unified for the first time, may have finally become the political equivalent of a force of nature—and a lesson for all the strongmen of our world.

Kaya GençKaya Genç is the author of Under the Shadow: Rage and Revolution in Modern Turkey. The paperback edition of his most recent book, The Lion and the Nightingale: A Journey Through Modern Turkey, featuring new material on the latest Turkish presidential election, will be published in May.