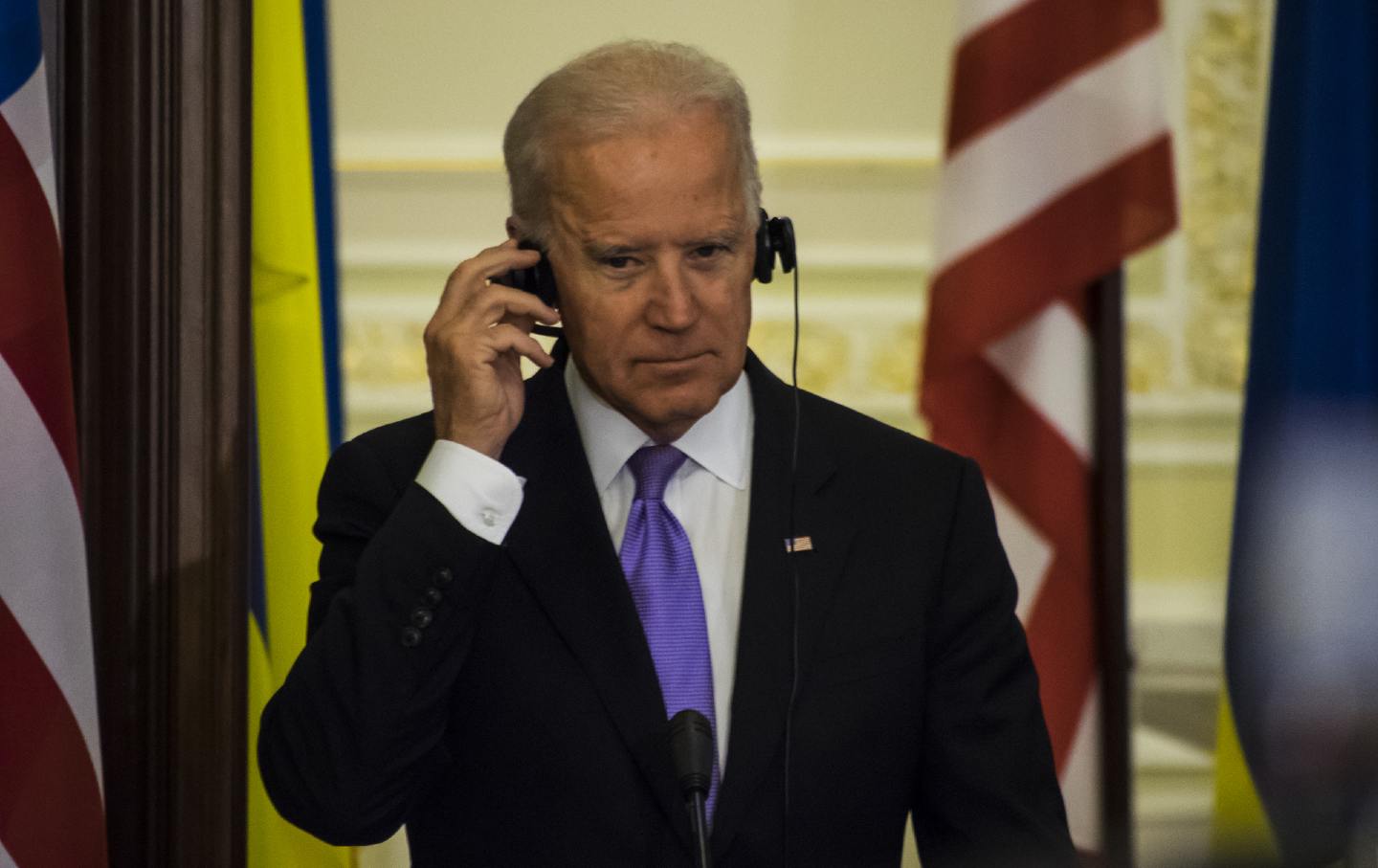

Then–Vice President Joseph Biden in Kiev, Ukraine, in November 2014. (Igor Golovniov / Shutterstock)

The kings, generals, and prime ministers who controlled Europe’s armies in the summer of 1914 didn’t think that their aggressive behaviors—issuing ultimatums, calling up reserves, massing troops on each other’s borders—would result in war. Rather, they believed that their conspicuous muscle-flexing would impel their rivals to back down, delivering a bloodless victory. But each show of force on one side prompted an even more extravagant riposte by the other, until the march to war became unstoppable—and so tens of millions perished.

Looking back to that time, it is not hard to see parallels with today’s precarious moment in Europe, with key players again issuing ultimatums, calling up reserves, and massing troops on each other’s borders. As this is being written, Russia is sending even more troops to the 100,000 or so already deployed in areas adjoining Ukraine, while the United States and its allies are dispatching additional forces to the NATO countries closest to Russia and Ukraine. If this military onrush is not halted soon, we can be drawn into another deadly conflagration—this time with nuclear weapons at the ready.

Let us be clear: While President Biden has ruled out direct US military involvement in Ukraine should that country be invaded by Russia, his generals are making plans for US combatants to assist Ukrainian soldiers in guerrilla operations against Russian invaders and to resupply Ukrainian forces from bases in adjoining NATO countries—moves that could easily result in American casualties and/or provoke Russian attacks on US/NATO staging areas, resulting in an escalating cycle of reprisals and counterattacks until American forces are engaged in a full-scale war with Russia. Given that US forces in the region include ships, planes, and artillery capable of striking deep within Russian territory and Russian forces possess comparable weaponry capable of striking well into NATO territory, combat between the two sides would likely involve damage to vital targets on each side, prompting further escalatory moves. Both sides have nuclear weapons deployed within reach of likely battle zones: The United States stores nuclear bombs in Europe for use by specially equipped F-16 and F-35 fighters, while Russia has nuclear warheads for its medium-range ballistic missiles.

Who is responsible for this insanity? Historians are still debating the origins of World War I, with some placing greater blame on Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, others on Britain, France, and Russia. Should we be so misguided as to proceed down that same path toward war—what the historian Barbara Tuchman termed a “march of folly”—future historians will no doubt engage in similar debates. Certainly Russia is to blame for igniting the current crisis, by deploying such a large force within striking range of Ukraine’s borders and by issuing ultimatums to the West, but the West also shares responsibility by rebuffing Moscow’s repeated warnings that its promise of eventual Ukrainian membership in NATO and the deployment of NATO forces in the former Soviet republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania posed a significant security threat to Russia.

What is important, at this point, is not apportioning blame for the current crisis but avoiding a disastrous train wreck. Issuing nonnegotiable positions—that Ukraine has an unalienable right to join NATO (the US/NATO stance) or that Ukraine can never join NATO and that the alliance must remove its forces from the Baltic states (the Russian stance)—will not lead to a peaceful outcome. The West must acknowledge that Russia possesses legitimate security concerns regarding its western approaches while Russia must accept that Ukraine cannot be made a vassal state of Moscow and that the Baltic states cannot be forced to abandon their ties to NATO. Both sides also need to affirm that they have a mutual interest in preventing the escalation of minor incidents into a major escalation, with possible nuclear consequences. Starting from these fundamental points, it should be possible to negotiate an outcome that gives both sides sufficient satisfaction to back away from confrontation.

A failure to adopt this approach would likely have catastrophic consequences. Should Russia invade Ukraine, or even occupy additional territory adjoining rebel areas in the Donbas, a major conflict will erupt and the US/NATO will be sucked into it one way or another, with unforeseeable consequences. Such a conflict could persist for months or years, turning Europe into a nightmarish war zone, or could escalate overnight into something far worse. And even if the conflict were contained at a relatively low level, the United States and its allies would likely sever most economic ties with Russia, causing severe hardship for the Russian population and for many in Europe itself. The bellicose environment in Washington, already at a frenzied level, would become even more delirious, preventing progress on any of the domestic issues so revered by progressives, such as voting rights, poverty reduction, and climate change.

This is not a matter that can be left to senior officials alone: We all have a huge stake in the outcome of this crisis. A failure by Biden and his top negotiators to find some common ground with their Russian counterparts would be a disaster for everyone on the planet. Our pleas for a peaceful outcome must be heard in Washington—and, to the extent possible, in London, Paris, Berlin, and Moscow.

Michael T. KlareTwitterMichael T. Klare, The Nation’s defense correspondent, is professor emeritus of peace and world-security studies at Hampshire College and senior visiting fellow at the Arms Control Association in Washington, D.C. Most recently, he is the author of All Hell Breaking Loose: The Pentagon’s Perspective on Climate Change.

The NationTwitterFounded by abolitionists in 1865, The Nation has chronicled the breadth and depth of political and cultural life, from the debut of the telegraph to the rise of Twitter, serving as a critical, independent, and progressive voice in American journalism.