Rage and Ruin: On the Black Panthers Rage and Ruin: On the Black Panthers

A new history of the party is too close to its subject, and misses the human drama.

Jun 5, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Steve Wasserman

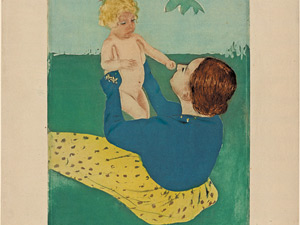

Transient States: On Mary Cassatt Transient States: On Mary Cassatt

In her printmaking the artist searched for a constantly elusive vision.

Jun 5, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Barry Schwabsky

Dirtying White Dirtying White

Why does Benn Steil’s history of Bretton Woods distort the ideas of Harry Dexter White?

Jun 5, 2013 / Books & the Arts / James M. Boughton

White Wigs, Black Masks: On Surveillance Pop White Wigs, Black Masks: On Surveillance Pop

The cameras no longer look at us because we’re famous; we’re famous because they look at us to death.

Jun 5, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Joshua Clover

The Anarchy Project The Anarchy Project

David Graeber’s account of Occupy Wall Street is essential—and somewhat maddening in its insistence on heightening the differences between anarchists and liberals.

May 31, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Danny Goldberg

‘Star Trek’ and the Twilight of Idealism ‘Star Trek’ and the Twilight of Idealism

Doesn't anyone dream of the stars in culture or in politics anymore?

May 23, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Michelle Dean

Hitler’s Classical Architect Hitler’s Classical Architect

Why is Léon Krier defending anew the work of the Third Reich’s master builder?

May 21, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Michael Sorkin

Shelf Life Shelf Life

Ralph Lemon’s Come Home Charley Patton

May 21, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Marina Harss

Attacks From Within: On Janet Malcolm Attacks From Within: On Janet Malcolm

The war between democracy and aristocracy in Janet Malcolm’s Forty-One False Starts.

May 21, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Mark Oppenheimer

Flappers and Philosophers Flappers and Philosophers

Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, Richard Linklater’s Before Midnight

May 21, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Stuart Klawans