Q&A With Sandra Tsing Loh on Her Provocative Theory About Menopause Q&A With Sandra Tsing Loh on Her Provocative Theory About Menopause

Menopause isn’t “The Change,” she says. Instead, fertility is what’s unusual.

May 14, 2014 / Jon Wiener

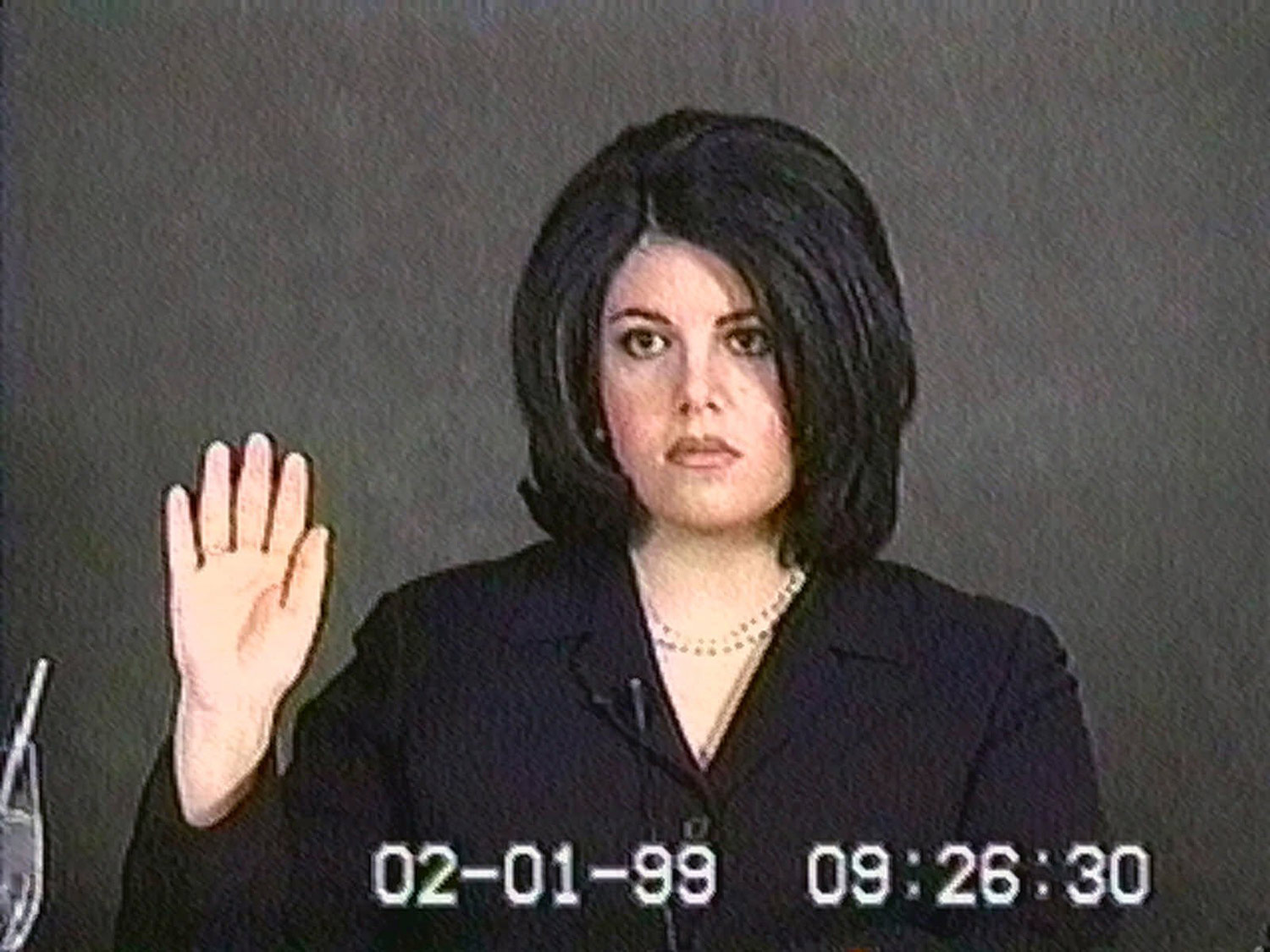

The Lewinsky Double Standard The Lewinsky Double Standard

If Monica Lewinsky were a man, she would have transcended the Clinton scandal long ago.

May 14, 2014 / Michelle Goldberg

‘Brown v. Board of Education’ Didn’t End Segregation, Big Government Did ‘Brown v. Board of Education’ Didn’t End Segregation, Big Government Did

Sixty years after the decision, it’s worth remembering it took Congress to finally smash Jim Crow.

May 14, 2014 / Ian Millhiser

The Trial of Cecily McMillan The Trial of Cecily McMillan

Cecily McMillan was arrested on the night of March 17, 2012, which fell on both St. Patrick’s Day and the six-month anniversary of the Occupy movement—a date that would also become known for the seventy-three arrests that occurred in Zuccotti Park that night. While the police were clearing the park of the throng of protesters, McMillan’s elbow struck NYPD Officer Grantley Bovell’s face. The defense argues that this event occurred when McMillan, leaving the park as directed, was suddenly grabbed from behind by her right breast; her elbow then struck Bovell as a reflex. The prosecution claims that McMillan deliberately elbowed Bovell without provocation while he was escorting her from the park. Throughout the case, the prosecution set out to distract the jury, and Judge Ronald Zweibel gave them free rein to do so, while consistently ruling key testimony and evidence for the defense as inadmissible. Several videos posted to YouTube show the crowd at Zuccotti Park from different angles on the night in question. However, the jury saw only a sliver of blurry footage. According to the defense, out of a ten-minute video showing the events before and after McMillan elbowed Bovell’s face, only fifty-two seconds were admitted. Another short clip was allowed without sound: this one shows McMillan convulsing on the ground after her arrest. In that audio, jurors would have heard voices in the crowd shouting at the police to help McMillan, which provides an important context to the officers’ passive observation of her quaking body. If McMillan were faking, as the prosecution alleged, it certainly fooled many of those present. McMillan’s character and history were not only scrutinized but mocked. When defense witness Yoni Miller described McMillan’s reputation in Occupy forums as the “queen of nonviolence,” Assistant District Attorney Erin Choi cried, “She is a fraud!” When Miller described seeing McMillan convulsing on the pavement, Choi flailed her arms and hips in an exaggerated fashion and archly asked if her imitation of a seizure resembled McMillan’s. The prosecution’s derisive and superficial portrait of McMillan, says Shay Horse, one of her supporters, is that of “a publicity-crazed millennial”—an image that dovetails with its claim that McMillan hit Bovell for attention from the cameras. In her closing arguments, Choi extended her jeering tone to general statements about assault and those who are assaulted. She said that Bovell would have needed iron hands to leave a bruise through clothing. Tim Eastman, who attended the closing arguments, tweeted: “Pros[ecutor] says Cecily is ‘not shy’ and therefore ‘would not have trouble reporting sexual assault.’” Any attempt by the defense to question Bovell’s character was quickly shut down by Choi and Judge Zweibel. Although Bovell’s involvement in a Bronx ticket-fixing scandal was discussed, the defense was prevented from addressing other, violent parts of his record. In 2010, Bovell was involved in a lawsuit against the NYPD for his participation in an incident in which NYPD officers ran a teenage boy on a dirt bike off the road. In 2009, he kicked a suspect in the face as he was lying on the ground. Bovell also allegedly assaulted Occupy protester Austin Guest on the same day as McMillan’s arrest. In her closing argument, Choi asserted that McMillan’s story would be more believable if she claimed that “aliens came down that night and assaulted her.” So let us consider: according to the prosecution, it’s more believable that an activist whose reputation is founded on nonviolence would decide to change her St. Patrick’s Day plans with friends in order to pick a fight with the police just to gain some attention (including elbowing one in the face once the cameras were rolling). Then, after her arrest, she instantly decides to fake a harrowing seizure and, at some point after her admission to the hospital, severely bruises her own breast for the purpose of framing an innocent policeman. Please support our journalism. Get a digital subscription for just $9.50! And this is the story that the prosecution (and, unfortunately, the jury) found more believable than the possibility that, on a night when protesters were being arrested in a manner that The New York Times described as “brutal and random,” an officer who once kicked a suspect in the face grabbed McMillan’s breast in a manner consistent with the pictures of her bruises entered into evidence, causing her to flail out with her elbow in a startled reaction. Or that an NYPD officer who was on probation at the time for his involvement in a ticket-fixing scandal would need a justification for the bruises on his prisoner and his public indifference to her medical distress? Ultimately, to Judge Zweibel and his court, it was more believable that this young woman is simply crazy than that this policeman could commit an act of sexual violence and then lie about it in a manner consistent with his personal history and the culture of the institution that employs him. It’s not even a good story, but it had a hell of an editor. In a just system, editors don’t belong in courtrooms—and Cecily McMillan doesn’t belong in prison. Read Next: Amity Paye on how, in some cases, Occupy activists may be making some police departments more accountable for their officers’ actions

May 14, 2014 / Kathryn Funkhouser

5 Concrete Steps the US Can Take to End the Syria Crisis 5 Concrete Steps the US Can Take to End the Syria Crisis

We in civil society must sharpen our demands.

May 14, 2014 / Phyllis Bennis

This Modern World This Modern World

May 13, 2014 / Tom Tomorrow

Snapshot: Scorched Earth Policy Snapshot: Scorched Earth Policy

A lone tree standing in what used to be a rainforest in Mato Grosso, Brazil. The country’s preparations for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics have furthered environmental damage, as Dave Zirin has reported in these pages. In a move that has outraged the citizenry, a stadium is being built in the Amazon.

May 13, 2014 / Bruno Domingos

‘Nation’ Exclusive: Edward Snowden and Laura Poitras Take on America’s Runaway Surveillance State ‘Nation’ Exclusive: Edward Snowden and Laura Poitras Take on America’s Runaway Surveillance State

“The first principle of any American intelligence official is not an oath to secrecy but a duty to the public, a commitment to speak truth to power.”

May 7, 2014 / Edward Snowden and Laura Poitras

Snapshot: Last Supper Denied Snapshot: Last Supper Denied

Plates by artist Julie Green illustrating final-meal requests by death-row inmates, including Clayton Lockett’s requested last meal: steak with A-1 sauce, shrimp with cocktail sauce, a baked potato, garlic butter toast, a pecan pie and Coca-Cola Classic with ice. The request was denied because it exceeded $15. He refused an alternative.

May 6, 2014 / Julie Green

Cold War Against Russia—Without Debate Cold War Against Russia—Without Debate

The Obama administration’s decision to isolate Russia, in a new version of “containment,” has met with virtually unanimous support from the political and media es...

May 1, 2014 / Katrina vanden Heuvel and Stephen F. Cohen