London

When I was a child at the end of World War II, I was told the good guys won. Reading David Cole’s remarks on drones [“Remote Control Killing,” March 4], I wonder. He writes, “We should not confuse [drones] with assassinations and torture.” Why not? The concept of the “rule of law” he invokes is meaningless as long as the authority to kill without due process is public policy; worse when that authority resides in one man. What profiteth a nation to win a war against fascism only to adopt its policies?

JEFFRY KAPLOW

Kansas City, Mo.

What has happened to The Nation? I wait for some discussion of the fascist takeover of our country and the world. When it was Bush, you covered crimes. Now with Obama, it’s just a slap on the wrist. David Cole, your legal affairs correspondent, says of drones, “We cannot forswear their use.” Yes, we must. Thanks to Katha Pollitt in the same issue, who writes more about the immorality of drones and kill lists.

ELIZABETH SMITH

New York City

David Cole is right that there is something very wrong with the Obama administration’s “targeted killing” program. It is shrouded in unnecessary secrecy, but publicly available information makes clear that the CIA and the military’s Joint Special Operations Command have killed hundreds of people without knowing very much about who they are, what they’ve done or whether they present a direct threat to the United States.

The administration’s former ambassador to Pakistan, who helped implement the targeted killing program there, has complained that the CIA regards “any male between the ages of 20 and 40” as a lawful target. The British-based Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which tracks drone strikes, estimates that as many as 4,300 people have lost their lives to US drone strikes in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen. Lindsey Graham, a senior member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, says the number of dead is even higher.

This is not only a human rights travesty; it is unwise and unlawful. Few things are more certain to swell the ranks of terrorist organizations than the perception that the United States is indifferent to the loss of innocent life. And international law is unambiguous: outside actual battlefields, lethal force may be used only against threats that are truly imminent, and then only as a last resort. The Justice Department white paper recently leaked to the press confirms that the administration’s targeted killing program does not observe these limits.

For moral, strategic and legal reasons, the program should be made more discriminating and more transparent. As Cole says, it should also be subject to judicial review—which should take place in federal courts, not in a new security tribunal set up specifically to issue death warrants. The federal courts are accustomed to evaluating the government’s use of lethal force in a domestic law enforcement context. They have also become accustomed to evaluating the lawfulness of national security detentions. They could certainly review the lawfulness of targeted killings.

Indeed, as the ACLU and the Center for Constitutional Rights are arguing in a case pending before a district judge in Washington, the Constitution requires the courts to do so. There is no need for a new “kill court,” and the creation of such a court would be more likely to normalize the targeted killing program than to narrow it.

JAMEEL JAFFER, deputy legal director

American Civil Liberties Union

New York City

As David Cole rightly notes, targeted killing can be lawful when the United States is in an armed conflict. It can also be lawful if the United States is acting within constitutional and international law recognizing the right of national self-defense. We have faced wars and imminent attacks in the past; we will face them again. We need to have a clear process governing how targeting decisions are made and how those rules are enforced when we do.

The US armed forces have such a process. The international law of war—embodied in treaties we have ratified, implemented through domestic regulations applicable force-wide—requires armed forces to establish systems of rules, training and discipline to make sure that targeting operations are conducted lawfully. The US military’s targeting doctrine, including its practices for how targets are chosen and checked, is designed to comply with this law and is available in a joint forces publication online. Members of the armed forces who violate orders within this system may be punished according to, among other things, the rules set forth by statute in the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Civilians, at least in Afghanistan, who wrongfully suffer damage from attacks (including the families of those killed) can seek amends through various US compensation programs there.

The military system is imperfect. Training requirements should be enhanced. Remedies for the wrongfully injured should be made more robust—including through the availability of civil remedies in US federal courts. But the current conflict has stretched the definition of what counts as an armed conflict, and who within it may be targeted; it is thus a policy-level responsibility to make clear and public which rules are applied. Still, there is a deep infrastructure not only of rules and regulations, but also of professional norms and culture here on which to build.

In substantial contrast, the CIA’s targeting authority is not limited by the statute passed by Congress authorizing the use of force against Al Qaeda and associates. The CIA, from what can be intuited from its rare public statements, does not necessarily consider itself legally bound by the law of war. According to some reports, the CIA has its own “kill lists,” based on its own criteria, which are publicly unknown. How CIA targeting personnel are trained to comply with what rules there are, what measures of discipline they may be subject to if they do not, what kinds of compensation may be made available to those who wrongfully suffer a misdirected attack—all of these are unknown.

It may be possible to develop an elaborate parallel system of rules, training and accountability mechanisms to ensure that the CIA complies at least to the same extent as the military with US and international law. Or there is another approach: relieve the CIA of its targeting mission.

What do we lose? Not capacity—over the past decade, the CIA and the military have come to work closely in joint operations, and intelligence and force capabilities can be shared while keeping operations under military legal authority. Neither need we lose secrecy—the military has proven itself able to operate in a remarkably clandestine fashion. What of deniability—the fiction that if the CIA is doing it, the government is not officially, diplomatically responsible? There are circumstances in which that may matter. But today, there is no one in the world who doubts that the United States is responsible for the ongoing drone operations in, for example, the tribal areas in Pakistan. For the price of shedding this fig leaf of denial, we could begin to reclaim the mantle of law.

DEBORAH PEARLSTEIN

Cardozo School of Law

Cole Replies

Washington, D.C.

Jeffry Kaplow and Elizabeth Smith equate targeted killing with fascism. That would make every country that has ever gone to war, even in self-defense, a fascist regime. There is plenty to be concerned about regarding Obama’s drone policy, but killing is a part of war and not in itself unlawful.

Notably, both Jameel Jaffer and Deborah Pearlstein—one at the ACLU and the other formerly with Human Rights First—agree with me that targeted killing, unlike torture, is sometimes permissible. The issue is how broadly the administration is employing this power, and subject to what checks and balances. I agree that the administration’s program remains unacceptably shrouded in secrecy, that it goes too far in extending beyond the battlefield to situations that do not pose an immediate threat, and that the CIA, which lacks the structure, experience and rules of the military, should not be conducting strikes. I’m skeptical that the administration believes it can target “any male between the ages of 20 and 40.” If that is really the case, why the reportedly extensive internal wrangling over who should or should not be on a “kill list”? They’re not spending all that time debating their targets’ ages. But there are serious unanswered questions about the scope of the administration’s “signature strikes,” which target people based not on individualized intelligence, but on patterns of activity. What should be clear—and what is uniting not only human rights activists and civil libertarians, but also voices on the right such as Rand Paul—is that the executive branch cannot be allowed the authority to kill in secret, far beyond the battlefield, without clear rules and public accountability.

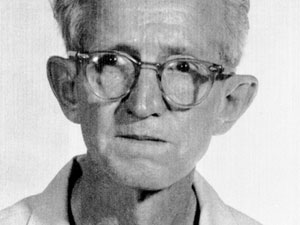

DAVID COLE Read More

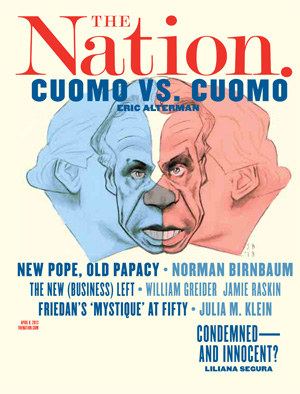

Our Readers and David Cole