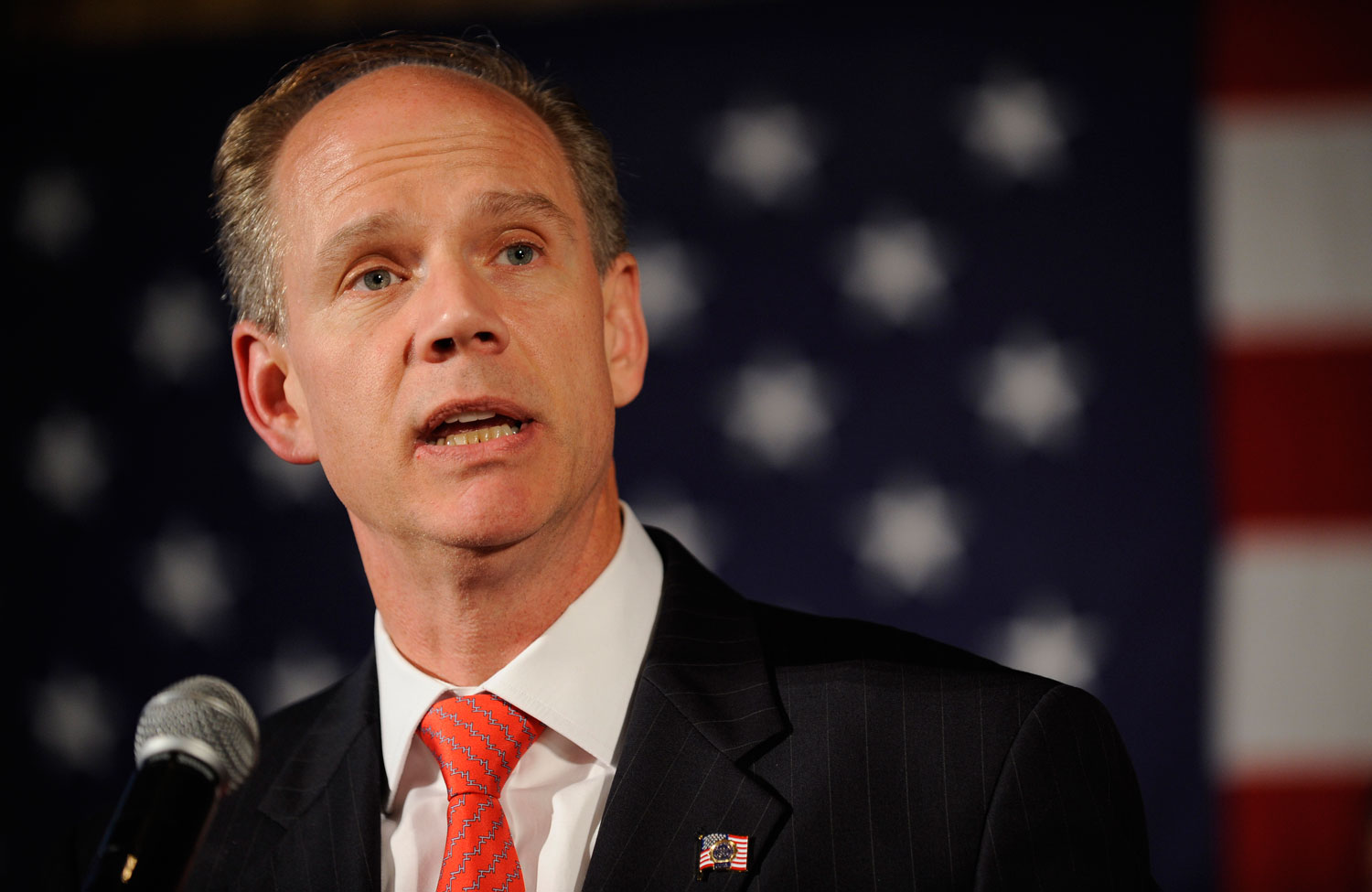

The District Attorney Who Failed to Secure an Indictment Against Eric Garner’s Killer May Be Running for Congress The District Attorney Who Failed to Secure an Indictment Against Eric Garner’s Killer May Be Running for Congress

Could the new civil rights movement thwart the Staten Island DA’s ambitions?

Jan 8, 2015 / Zoë Carpenter

The NYPD’s Long War The NYPD’s Long War

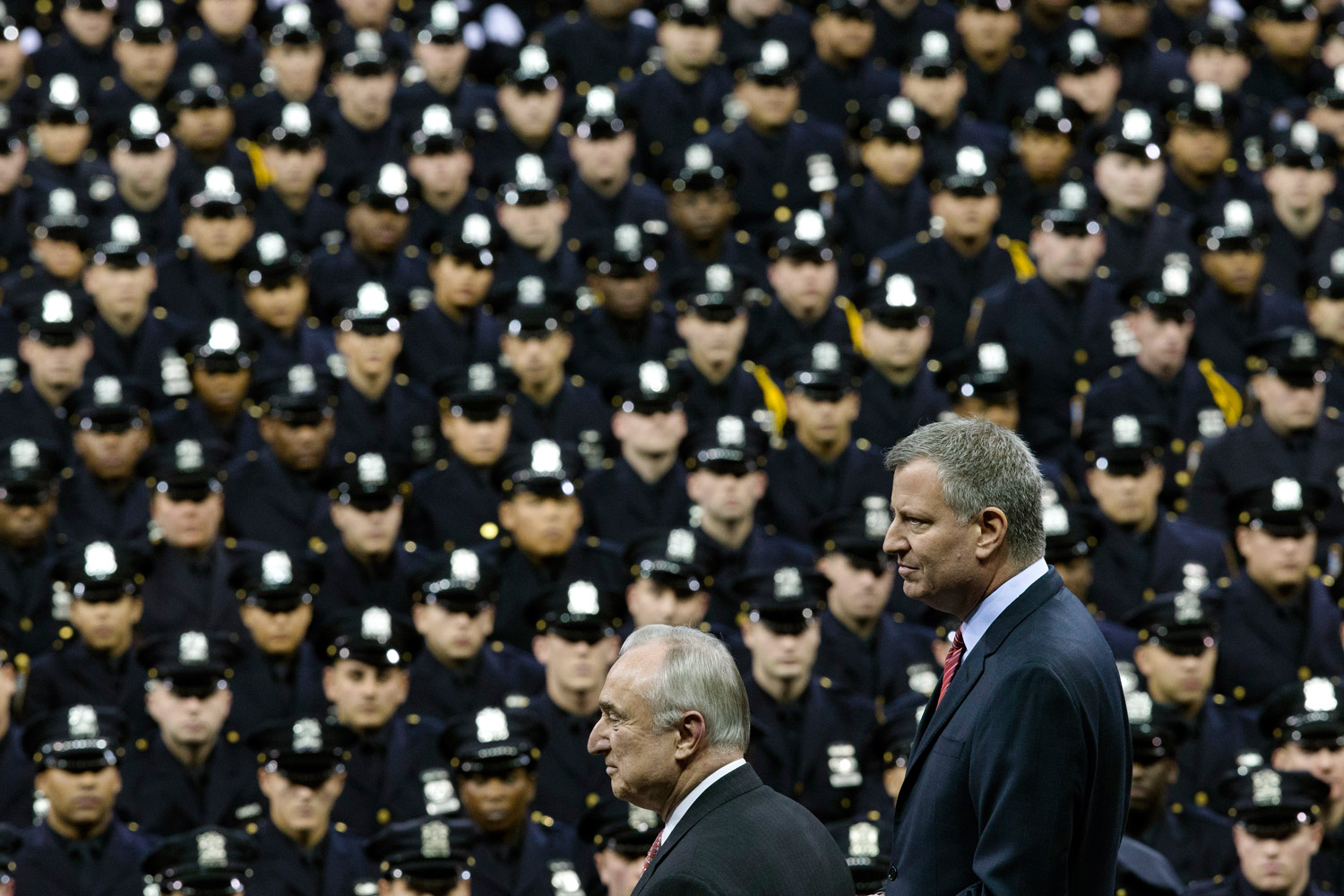

The leaflet was meant to highlight the police department’s anger with the mayor of New York. It encouraged officers to fill in their names on a document that read: “I, …, a New York City police officer, want all of my family and brother officers who read this to know in the event of my death” that the mayor and police commissioner should “be denied attendance of any memorial service in my honor as their attendance would only bring disgrace to my memory.” That’s how deep the divisions ran. Yes, “ran.” The leaflet was distributed in 1997. The mayor in question was Rudolph Giuliani, and his critics were rank-and-file members of the powerful Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA). Though the union did not officially sanction that jab at that mayor, its circulation among officers “demonstrates the depths of their discontent,” reported a New York Times article on a contract dispute in which Giuliani was taking a hard line against pay increases. Today, NYPD officers can download a similar document from the PBA’s website and sign it as part of the protests against Mayor Bill de Blasio. The mayor angered PBA president Patrick Lynch and many union members by recognizing the tensions between minority communities and the NYPD—including outright fear of the police—after a grand jury decided not to indict an officer who was videotaped placing a choke hold on Eric Garner immediately before the Staten Island man’s death. That anger has drawn national attention recently, as officers turned their backs on the mayor as he delivered eulogies at the funeral services for Officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu, who were shot and killed in their squad car on December 20. In a more extended show of pique, officers have also engaged in a citywide work slowdown, widely believed to have been inspired (if not coordinated)by the PBA and other key police unions. As raw as the tensions are in the city now, it is vital to recall that New York mayors have regularly clashed with the police union and its leadership. These clashes have been bitter and have often lasted for years, as a powerful and politically savvy union has regularly positioned itself to exploit both sympathy for cops and fears regarding crime. Even the tactics are consistent: officers upset with Mayor Robert Wagner Jr. and his police commissioner engaged in a slowdown in 1960, and the commissioner spoke publicly of fears that the police would stage a sick-in to disrupt presidential voting in the city that same year. Some mayors have taken harder hits than others: David Dinkins, who incurred the wrath of the PBA when he established the framework for the current incarnation of the city’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, was narrowly defeated for re-election in 1993. Today, there are plenty of attempts to compare him to de Blasio (a former Dinkins aide). Yet Dinkins is the exception, not the rule. Most New York mayors who have clashed with the PBA and its members have survived, even thrived, politically. In the 1930s, Fiorello La Guardia had repeated run-ins with the NYPD over its brutal treatment of union organizers and left-wing protesters. Things got so intense that La Guardia’s police commissioner resigned amid complaints about the “numerous encouragements which [the mayor] gave to public disorder.” Even so, La Guardia was easily re-elected in 1937 and again in 1941. The same held true for Wagner: after the slowdowns in his second term, the PBA hailed Attorney General Louis Lefkowitz, the mayor’s Republican challenger, but Wagner was re-elected in 1961 with a 400,000-vote margin. So it has gone across most of the city’s modern history. Rank-and-file police officers have protested, and their union has stirred up fury, but the voters have tended to side with the mayor, not the cops. This hasn’t been out of disrespect for law enforcement so much as an understanding that oversight is needed to check and balance the power of a massive police department, and that strong mayors can and should provide such oversight. This is the most important lesson for Mayor de Blasio to take away in the current conflict with the PBA, which comes amid broader wrangling over contracts, pensions and departmental reforms. De Blasio needs to recognize that history is on his side, and that if he stands up to the PBA with the same resolve as past mayors, he can achieve reforms and win elections. Yes, he can note the cautionary (and complex) tale of Dinkins’s defeat, but he would be far wiser to recall the redemptive tales of hard-won victories, like those of John Lindsay. Elected in 1965 on a promise to reform the NYPD, Lindsay appointed former federal judge Lawrence Walsh to head a Law Enforcement Task Force charged with reviewing police operations, named a reform-minded police commissioner, and worked closely with the NYPD’s new chief inspector, Sanford Garelik, who talked of “humanizing the department.” Lindsay clashed continually with the PBA—so much so that the union’s spokesman, Norman Frank, prepared to challenge the mayor’s 1969 re-election bid. Frank stepped aside when prominent “law-and-order” candidates entered the race. One such candidate beat Lindsay in the GOP primary, while another won the Democratic nod against more liberal rivals. It seemed for a moment that Lindsay was doomed, yet he and his supporters regrouped, mounting a fall campaign on the Liberal Party line. By uniting reformers across the political spectrum and garnering strong support from minority communities, Lindsay easily beat his Democratic and Republican opponents that November. Among his campaign themes was a reminder that his emphasis on improving police/community relations had kept New York relatively calm even as other cities exploded in riots. Years later, in an essay on Lindsay’s mayoralty, Charles R. Morris observed that, while Lindsay’s reforms were “hard for cops to swallow,” the fact remained that “on any fair judgment, the strategy mostly worked.” Morris continued: “For a brief period Lindsay was ‘America’s Mayor,’ and other mayors began consciously to pattern their policies after his.” Please support our journalism. Get a digital subscription for just $9.50! New York is different from the city it was in the late ’60s and even the ’90s. And de Blasio is different in many ways from his predecessors. Yet there is good reason to believe that this mayor can learn the lessons of the past and apply them to the future. The past tells us that it is possible for a strong mayor to survive clashes with a strong police union. New York likes strong mayors, especially when they take on entrenched bureaucracies and address long-neglected problems. The key is to keep communicating with the police and the electorate, and to explain why change is not just an option but a necessity. This is the historical reality, as opposed to the frenzied media spin of the moment. And it is this reality that Mayor de Blasio would do well to keep in mind throughout the weeks and months to come. Read Next: The editors on protests and the killings of the NYPD officers

Jan 7, 2015 / John Nichols

How Police Departments Can Mend the Rift With the Public How Police Departments Can Mend the Rift With the Public

Police must be taught that the power entrusted to them is not theirs to use or abuse as they see fit.

Jan 7, 2015 / Frank Serpico

5 Books: Who Polices the Police? 5 Books: Who Polices the Police?

Alex Vitale is an associate professor at Brooklyn College specializing in urban politics and policing. “Popular concern with policing has long been driven by high-profile tragedies,” he says. “What’s new is people organizing against more mundane forms of mass criminalization, like stop-and-frisk and ‘broken windows’ policing.” How should we understand these new battles? Vitale offers five starting points. PUNISHED Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys by Victor M. Rios Buy this book This powerful ethnography, a favorite of my students, tracks the corrosive effects of policing and the criminal-justice system on low-income young people of color in Oakland. Rios’s close connection with them allows him to tease out the ways in which they adapt to the constant harassment and humiliation of the “youth control complex,” on the streets and in school, enforced by the police. What often results is a vicious cycle of criminalization and incarceration, and these young men attempt to maintain their dignity in ways that often backfire, deepening their social and economic isolation. OUR ENEMIES IN BLUE Police and Power in America by Kristian Williams Buy this book This taut antiauthoritarian manifesto provides a well-researched overview of the oppressive nature of American policing. While sometimes engaging in generalizations and ad hominem attacks, its unapologetic indictment of the police provides a refreshing antidote to the liberal pleadings that police can be improved with a bit more training. Williams reminds us that the origins of American policing lie in racial oppression and class division. He looks to communities of revolutionary struggle—the IRA in Northern Ireland and the ANC in apartheid South Africa—for examples of self-policing. HUNTING FOR “DIRTBAGS” Why Cops Over-Police the Poor and Racial Minorities by Lori Beth Way and Ryan Patten Buy this book This groundbreaking study relied on hundreds of hours of police-car ride-alongs in two unnamed cities. While police often say that arrest rates are racially skewed because minority neighborhoods produce crime, Way and Patten found that officers looking to make arrests go out of their way to target people of color for drug violations and other petty crimes, often leaving their assigned patrol areas to “hunt” for such easy arrests. The book further proves that the “war on drugs” encourages the over-policing of communities of color. COP IN THE HOOD My Year Policing Baltimore’s Eastern District by Peter Moskos Buy this book This highly readable ethnography reveals the pointlessness of contemporary urban-policing practices. Most striking is its portrayal of the utter futility of the “war on drugs” from the perspective of both the police and low-income communities of color. Moskos gets deep into the origins of “vice” policing and describes in painful detail the corrupting influence of quotas and other numeric performance measures, showing how they produce unnecessary arrests, undermine relations between the community and cops, and devalue preventive policing. CITIZENS, COPS, AND POWER Recognizing the Limits of Community by Steve Herbert Buy this book This study of West Seattle demonstrates that so-called community policing expands police power rather than empowering civilians. Communities don’t have the organization or expertise to counter the bureaucratic weight of local police. Instead, police/community interactions become an opportunity for police to produce the appearance of cooperation while encouraging residents to provide information. Herbert’s findings suggest that demands for community control are doomed to failure, and that we should look to larger political structures to control the police.

Jan 1, 2015 / Alex S. Vitale

Lesson Learned: High School Hoops Team Disinvited From Tournament Over ‘I Can’t Breathe’ Shirts Lesson Learned: High School Hoops Team Disinvited From Tournament Over ‘I Can’t Breathe’ Shirts

The Mendocino high school basketball teams are learning an ugly lesson in the boundaries of free speech.

Dec 27, 2014 / Dave Zirin

Why #BlackLivesMatter Actions Aren’t Stopping Why #BlackLivesMatter Actions Aren’t Stopping

Policy experts and activists explain what’s keeping people in the streets and what the movement should consider next.

Dec 16, 2014 / Dani McClain

The Criminal Justice System Is Broken. Here’s How to Start Fixing It. The Criminal Justice System Is Broken. Here’s How to Start Fixing It.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman wants his office to be able to prosecute cases in which police officers kill unarmed citizens.

Dec 16, 2014 / Katrina vanden Heuvel

The Power of Political Athletes to Puncture Privilege The Power of Political Athletes to Puncture Privilege

By breaching the walls of the sports world, we can puncture the ultimate privilege in our society: that of blissful ignorance.

Dec 12, 2014 / Dave Zirin

Is Racial Justice Possible in America? Is Racial Justice Possible in America?

We need law and policing reform, but first we have to want to end state-sanctioned violence against African-Americans.

Dec 10, 2014 / Feature / David Dante Troutt

It’s 1963 Again It’s 1963 Again

Last August, some observers drew comparisons between the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by Officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, and the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. The announcement on December 3 that a Staten Island grand jury had chosen not to indict the policeman who choked Eric Garner to death might indicate that we are closer to 1963—when a series of devastating setbacks and the subsequent widespread outrage transformed the civil rights struggle. There was a perfect storm this past month: the continuing fallout from a grand jury’s decision not to indict Wilson in Ferguson; the identical outcome in the Garner case; a Cleveland newspaper’s efforts to discredit and sling mud at the parents of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy also killed by police. This moment has the potential to catapult change, just as a series of events did eight years after Till’s death. The 1963 murder of four black girls at Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church hit Americans square in the chest, reminding them of the Jim Crow system of justice in which black people had no rights that whites were bound to respect. The little girls were killed in September of that year in a place already dubbed “Bombingham” for the level of violent racist backlash against the city’s small progressive steps. Martin Luther King Jr. had been jailed there in the spring. Medgar Evers had been assassinated that summer in Mississippi. We find ourselves at a similar moment fifty years later—with “Again?” on our lips and a familiar feeling of horror at the video of Officer Daniel Pantaleo choking Garner to death, the unsparing force he uses against a man gasping over and over again, “I can’t breathe.” With the killings of Brown, Garner, Rice, unarmed New Yorker Akai Gurley and others, we are all reminded that black life is still devalued, and that police officers are too often treated as if they were above the rule of law. It is all coming so quickly: these announcements that a trial isn’t even necessary to determine a police officer’s guilt or innocence; these exonerations through other means. As a result, people are taking to the streets in Ferguson, New York City, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Boston, Cleveland and beyond. Please support our journalism. Get a digital subscription for just $9.50! To turn that outrage into progress, we should start to think big. A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker and other brilliant strategists of yesteryear knew that a successful struggle requires goals, not just reaction. Right now, activists from organizations like Millennial Activists United, the Ohio Students Association, Dream Defenders and Make the Road New York are demanding that the federal government prosecute police officers who kill or abuse people; that independent prosecutors be appointed at the local level and charged with prosecuting officers; and that the Justice Department deny funding to police departments that use excessive force or racial profiling. Several activists met with President Obama on December 1 to push these goals. This is beginning to look like playing offense. It’s worth noting that the public outcry in response to the rapid-fire events of 1963 is credited with making passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act inevitable. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom had taken place not even a month before the Birmingham church bombing, showing the world that a critical mass of people were mobilized in the service of fundamental change. If the history of this country’s most revered period of revolutionary change is any guide—and if a policy program is developed to channel all this growing energy—then we’re just getting started.Dani McClain Read Next: Gary Younge on “black-on-black” crime

Dec 10, 2014 / Dani McClain