How John Roberts Went Full MAGA How John Roberts Went Full MAGA

A revealing article in The New York Times details how the chief justice put his thumb on the scale for Trump to keep him on the ballot and out of jail.

Sep 17, 2024 / Elie Mystal

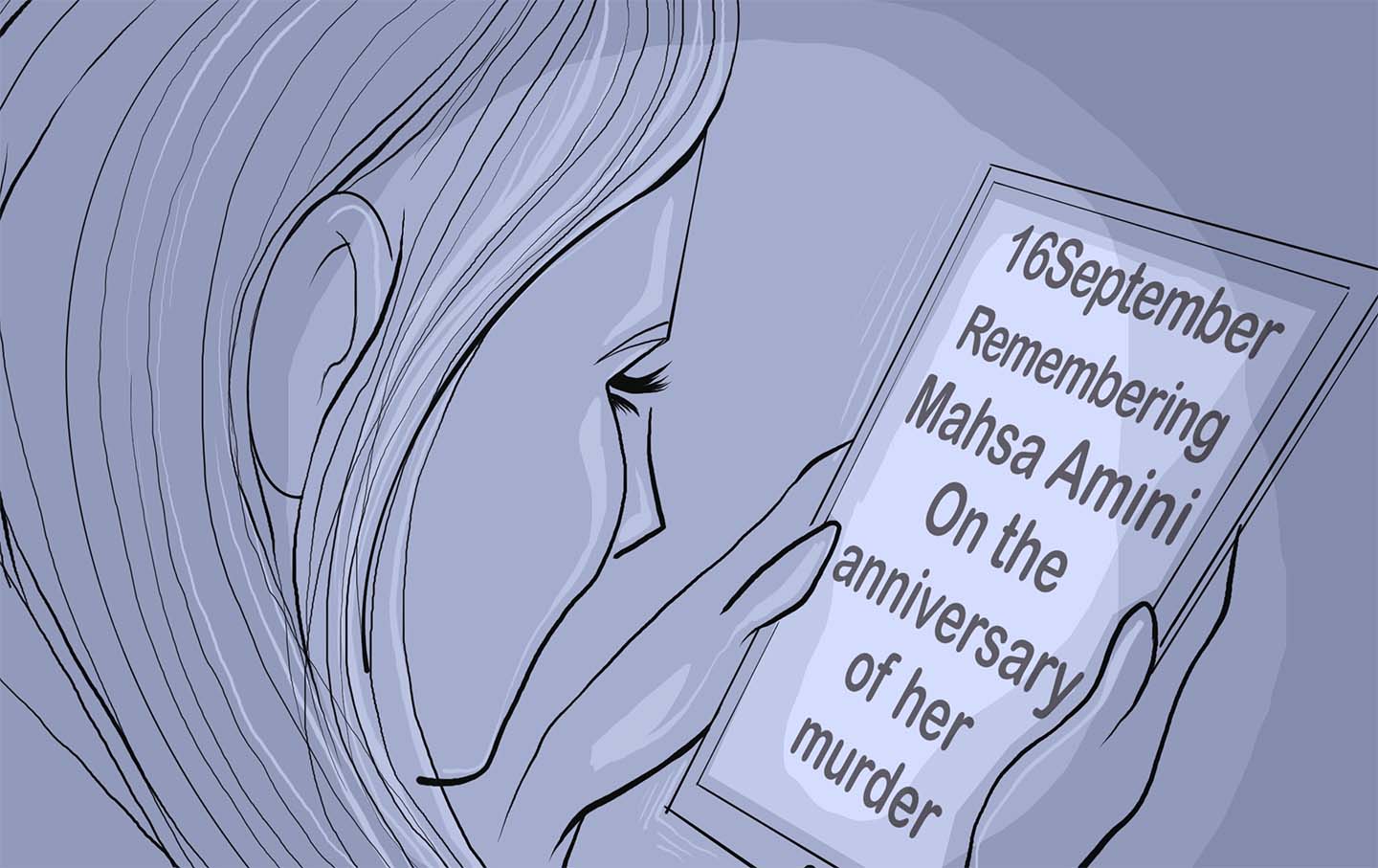

A September 16 Remembrance A September 16 Remembrance

of Mahsa Amini on the anniversary of her murder.

Sep 17, 2024 / OppArt / Nasrin Sheykhi

Is Eric Adams’s Luck About to Run Out? Is Eric Adams’s Luck About to Run Out?

Losing one police commissioner might be merely careless. But losing two—with a number of federal investigations targeting the mayor’s inner circle—has encouraged challengers.

Sep 17, 2024 / Ross Barkan

Disabled Union Members Are Strengthening the Labor Movement Disabled Union Members Are Strengthening the Labor Movement

Disabled workers are getting louder and more effective as they push their unions to be more accessible and inclusive. All workers are benefiting.

Sep 17, 2024 / s.e. smith

Israel Has Bombed Gaza's Healthcare System Back to the 19th Century Israel Has Bombed Gaza's Healthcare System Back to the 19th Century

Gaza's doctors are frequently working in conditions not seen since before the Civil War.

Sep 17, 2024 / Abdullah Shihipar

The Brooklyn Potluck That Helped Black Literature Flourish The Brooklyn Potluck That Helped Black Literature Flourish

In Courtney Thorsson's cultural history The Sisterhood, she details how intimate gatherings played a role in the golden age of Black women's writing.

Sep 17, 2024 / Books & the Arts / Marina Magloire

JD Vance Can’t Even Bullshit Properly JD Vance Can’t Even Bullshit Properly

Donald Trump is a world-class BS artist. His running mate is just a twitchy liar.

Sep 16, 2024 / Jeet Heer

Private Equity Steps Up to the Plate Private Equity Steps Up to the Plate

Diamond Baseball Holdings is taking over minor league baseball and reaping the benefits of hundreds of millions in taxpayer subsidies.

Sep 16, 2024 / Amos Barshad

How the Liberal Media Gave Us JD Vance How the Liberal Media Gave Us JD Vance

The months-long romance between Vance and an easily duped press in 2016 led directly to his sordid political rise.

Sep 16, 2024 / Chris Lehmann

Kamala’s Capitalist Class Kamala’s Capitalist Class

Both parties have little trouble attracting support from the superrich. But a closer look reveals fissures within the ruling class.

Sep 16, 2024 / Doug Henwood