Chris Hayes: How Trump Wins the Battle for Attention

On this episode of Start Making Sense, the MSNBC host says information is infinite, but attention is limited and that’s what makes it valuable.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Our attention is limited. That makes it valuable, Chis Hayes says– not just to us, but to those who’d like to exploit it. Chris’s new book is The Sirens’ Call: How Attention Became the World's Most Endangered Resource; before he became host of “All in with Chris Hayes” on MSNBC, he was The Nation’s Washington Correspondent.

Also: Your Minnesota Moment: officials in sanctuary cities and counties in Minnesota face threats from the Trump administration. Host Jon Wiener explains the threats to undocumented residents from Stephen Miller, and the response from Minnesota’s Attorney General Keith Ellison.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

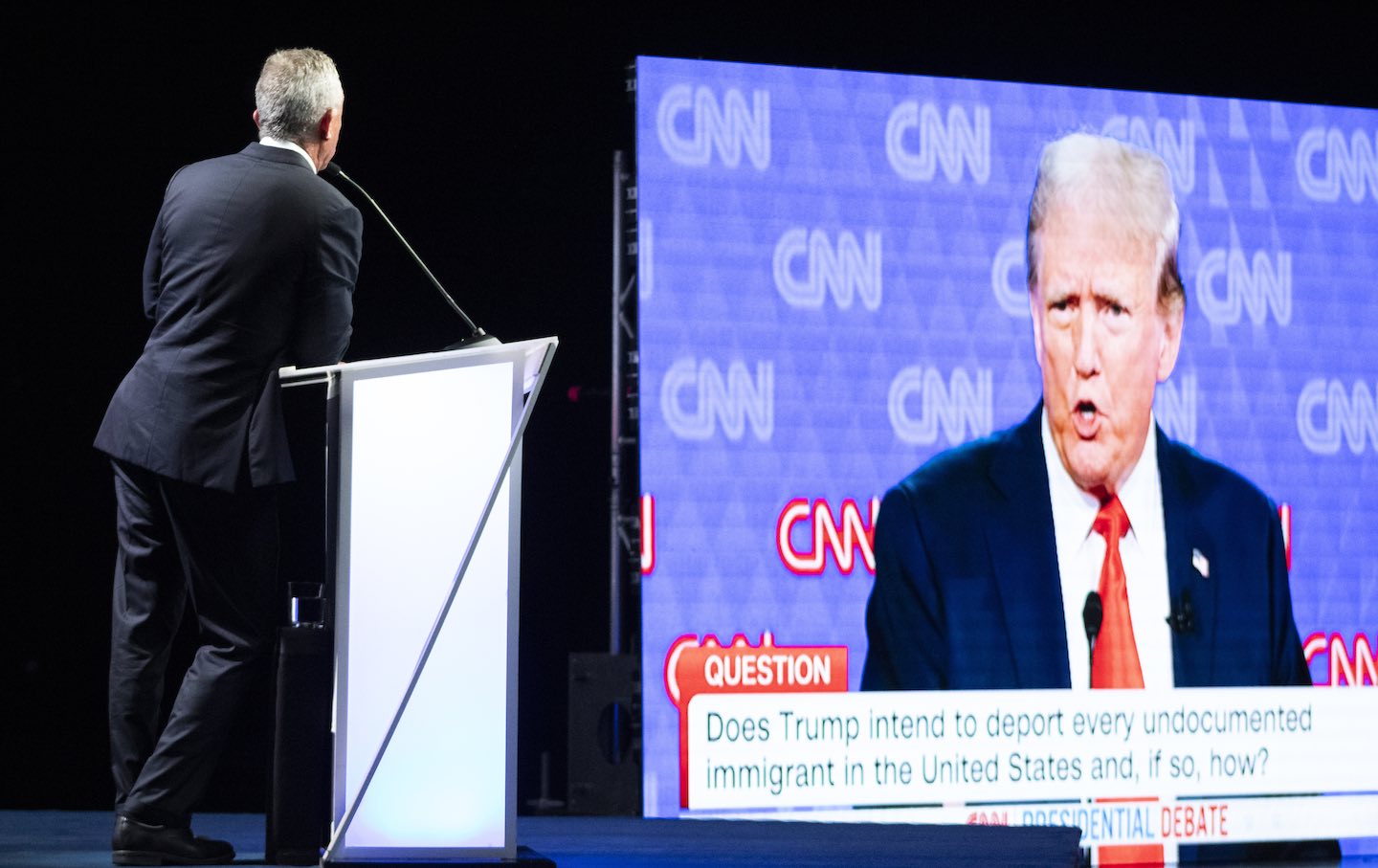

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. watched former president Donald Trump respond to a CNN presidential debate question during “The Real Debate” in Los Angeles, Calif., on Thursday, June 27, 2024. (Caylo Seals / Sipa USA via AP Images)

(Caylo Seals / Sipa USA via AP Images)Our attention is limited. That makes it valuable, Chis Hayes says– not just to us, but to those who’d like to exploit it. Chris’s new book is The Sirens’ Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource; before he became host of “All in with Chris Hayes” on MSNBC, he was The Nation’s Washington Correspondent.

Also on this episode, Your Minnesota Moment: officials in sanctuary cities and counties in Minnesota face threats from the Trump administration. Host Jon Wiener explains the threats to undocumented residents from Stephen Miller, and the response from Minnesota’s Attorney General Keith Ellison.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Republicans are about to end Obamcare subsidies, driving up premiums for 20 million people during the year of the midterm elections. How have they managed to end up after all these years with no health insurance plan of their own? John Nichols comments.

Also: Bob Dylan’s earliest recordings have just been released—the first is from 1956 when he was 15 years old—on the 8-CD set ‘Through the Open Window: The Bootleg Series vol. 18” – which ends in 1963, with his historic performance at Carnegie Hall. Sean Wilentz explains – he wrote the 120 page book that accompanies the release.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Jon Wiener: From The Nation magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the show: sanctuary counties for undocumented residents in Minnesota face threats from the Trump administration. But first, Chris Hayes talks about the competition to get us to pay attention – to products, and to people, especially you-know-who. The basic fact of life is that our attention is limited. That makes it valuable – not just to us, but to those who’d like to exploit it. We’ll explain everything, in a minute.

[BREAK]

I have a friend who refuses to watch Trump on TV. Why not? “Because,” he says, “Your attention is the most valuable thing you have.”

Chris Hayes has been thinking about that idea for a while, and now he’s written a book about it – with the wonderful title, The Sirens’ Call. Chris Hayes started out writing for The Chicago Reader, then In These Times, then in 2007, The Nation named him its Washington D.C. editor. Then he went to NBC, of course, became host of All In with Chris Hayes, which won an Emmy. And he writes books: Twilight of the Elites, and A Colony in a Nation. We talked about each of them here. His new book, The Sirens’ Call, is subtitled, How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource. Chris Hayes, welcome back.

Chris Hayes: It’s great to be back.

JW: We have to start with your wonderful title, The Sirens’ Call. Remind us about the sirens in The Odyssey. They are irresistible, but deadly.

CH: Irresistible but deadly, yes. As Odysseus is leaving Circe, the goddess, she warns him about what’s coming next. And her warning saves his life. And basically, she says there are these sirens who will lure men to death. They warble them to death with their song, it’s irresistible, you crash upon the rocks and your family will never see you again. And she gives him a plan, which is to resist the sirens’ call, to bind himself to the mast of his ship, to stuff wax in the ears of his crew so they can’t hear the sirens’ call, and so he can listen to the sounds and sail safely past.

And of course, just as Circe predicted, when the moment comes, even though Odysseus has prepared himself for this moment, he’s wriggling on the mast trying to get his men to pay attention to him and to steer the ship towards them, because that’s how irresistible they are. And yet because he’s bound to the mast and because the men’s ears are stuffed with wax, he’s safe. And I start with that image, and it’s the title image of the book because I think that experience of being bound to the mast of desperately trying to manage our own attention from moment to moment is essentially the condition to modern life.

JW: And as an example, you describe your own struggle to resist the sirens of our time, especially in the morning when you sit on the couch. Could you read us those lines from the opening of your book?

CH: “In the morning, I sit on the couch with my precious younger daughter. She’s six years old, and her sweet soft breath is on my cheek as she cuddles up with a book asking me to read to her before we walk to school. Her attention is uncorrupted and pure. There is nothing in this life that is better. And yet I feel the instinct, almost physical, to look at the little attention box sitting in my pocket. I let it pass with a small amount of effort, but it pulses there like Gollum’s ring.”

JW: And what is it that you call “the single most distracting device in history”?

CH: Well, it’s certainly the smartphone. And I think that the introduction of the iPhone in 2007 by Steve Jobs is a useful marker of the beginning of this age. And I think it’s a culmination of a lot of forces. One of the points I’m trying to make in the book is that it’s not just the phone. The phone is kind of a byproduct in some ways, an inevitable byproduct, that there’s deeper forces that produce the attention age, which is what we live in, but really the marker of its beginning is the introduction of the phone.

JW: But of course, cultural conservatives and old people have always complained about the new forms of culture and media: things are always going downhill fast, “kids these days are no damn good,” my father-in-law was shouting, “This country is finished,” 50 years ago. In the ‘50s, experts said comic books were causing juvenile delinquency. In the 19th century, experts said reading novels was dangerous for women. Is this anxiety about screen time just another round of fear of the new something we’ll get over, the way we don’t worry that TV will destroy society? Is there really any difference?

CH: I think there is. Although I also think it’s really important to wrestle with this question because it really is the case. And I extensively quote in the book, my favorite is a quote from, I think, the 1890s where a critic is talking about magazines. And it’s a great quote. He says, “These days after dinner, the family sits around and they’re not talking to each other and interacting. They’re each in their own magazine.” And it’s so wonderful because it’s precisely the complaint that we have, of course, today about phones. So I think there’s two ways to think about. One is that you can look at a lot of these critiques of the development of modern media and the growth of this kind of form of attention capitalism at each point as overblown. Or you can also say that at each point up this curve of modernity, there was something pretty crazy happening.

So when – in Plato, Socrates criticizes the new technology of writing because it’s going to make it so men don’t remember things anymore. And at one level it seems sort of preposterous, but it’s also true that writing utterly transformed human relations, right? And human forms of knowledge. And when Henry David Thoreau goes to Walden Pond, he calls these sorts of things we’re making for ourselves, and we think that there’s God in there, but the devil is in them, basically. And the enduring appeal of Thoreau is the fact that he’s onto something as well. So part of my point is that these critiques, this line of critique, you can view it at each circumstance as hyperbole, or you can also say there’s actually something profoundly alienating about the specific development of this aspect of modern life at each stage of its development. And we’ve reached to me a kind of culmination of that in the attention age.

JW: Initially this was called “the age of information” because information now is infinite. But you say there’s a second factor. What’s that?

CH: I think that the common way we understand the sort of central characteristic of our age is the information age, meaning moving from an economy centered on the production of items that transform atoms, physical transformation to ones and zeros that transform bits. And we all understand this, right? Like a claims adjuster in a health insurance company, she’s not physically moving anything. She’s not forging steel. She’s not on an assembly line. What she’s manipulating is essentially information, and that’s become more and more and more central to global economic life, and particularly American economic production. My point is that it’s a mistake to understand information as the central aspect of this form of economic relations. Because information is infinite and cheap. There’s tons of information. It’s easily replicable, you can copy information and when you move it from one place to the other, you don’t have to take it from that place. The resource that’s finite in the information age as we call it, is actually attention.

JW: Information is infinite, attention is limited.

CH: Exactly. And information is cheap, and attention is expensive. And that’s precisely because attention can only be in one place at one time. So there’s an example I quote from Lawrence Lessig, which is great, where he’s talking about the difference between property and intellectual property. And he says, “If you put a picnic table in your backyard and your neighbor copies the idea of a picnic table in his backyard, he hasn’t done anything to change your life, there’s just someone’s next door. But if he takes your picnic table, then that’s really different. Then now he has your picnic table, and you don’t.” That’s what attention is like. Attention’s like the picnic table in the example. Information’s like the idea of the picnic table. If someone takes your attention, they have it, and you no longer do.

JW: Well as a primetime nightly TV news anchor with millions of viewers, you write, I quote, “Every waking moment of my work life revolves around answering the question of, ‘How do we capture attention?'” It’s not easy, but you have succeeded for more than a decade now. Can you tell us, what works on your show to keep people’s attention and what doesn’t? Or are those trade secrets?

CH: That’s a good question. I mean, look, a lot of it is just craft and technique of storytelling. Honestly, I have not reinvented the wheel. I’ve gotten better as a storyteller. But then part of it too is understanding where public attention is flowing at a given moment and working with it as opposed to against it.

Which means there’s all sorts of stories you could do that are essentially kind of “out of nowhere” that might be interesting. But if that’s all you do, you’re working against the sort of forces of public attention. So you can’t just work in contrary to them. You also can’t just let them determine everything you do. You have to sort of figure out this relationship to the vagaries of public attention where you have your principles and your perspective and your agenda, things that you think are important, but you also are dealing with the external push and pull and demands of audience attention as a real force in the world, the way a sailor encounters the wind. And you have to sort of navigate the ship with that in mind. And that, I think, is a skill that I’ve really gotten better at and developed over the years.

JW: You say this pursuit of attention is a transformation as profound as the creation of wage labor is the central form of human toil. You described how attention is now a commodity in the same way labor became a commodity in the early years of the Industrial Revolution. And you quote Karl Marx on the earlier transition from work to labor in his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. Could you read that passage, please, that’s quoted in your book?

CH: So this is Marx in Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844: “The worker does not feel content, but unhappy does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself.” This was the fundamental insight of Marx’s theory of labor and alienation, that a social system that had been erected to coercively extract something from people that had previously, in a deep sense been theirs. Even today, those words feel fresh.

JW: “Even today, those words feel fresh”: Karl Marx on alienation from his 1844 manuscripts, one of the fundamental works of our time, one of my favorite pieces of writing. I think you may be the first person in the history of this broadcast to quote them. So thank you, Chris Hayes.

CH: [Laughter] That’s amazing. There’s quite a bit of Marx actually in the volume.

JW: There is. Of course, what we’re really interested in here is politics, how people competing for power gain the attention of potential supporters. How can we progressives gain the attention of potential supporters, and then how can we hold onto their attention? Please tell us the answer.

CH: Well, I mean this is one of the things that I think I’ve come to conclude is that capturing attention is art, not science. And I think it’s probably useful to think about attention as existing in sort of two different realms with us. There are the things that at scale will reliably grab attention, the loud and obnoxious, obscene, the period and the lurid, we sort of know those categories, Donald Trump is sort of all of those things in many ways, and that is what enormous competitive attentional markets will select for. Because when you’re competing with everyone against everyone else, those are the kinds of things that are going to reliably at scale, capture attention.

But at the same time, one of the amazing things about what people will pay attention to is that it’s endlessly varied. There are people that will watch operas, there are people that will binge obscure television shows, there are people that will sit and look at a sculpture for an hour or listen to a symphony for two hours, I mean, I will watch carpet cleaning videos online. Something I didn’t even know existed until recently.

JW: Wait a minute, carpet cleaning videos?

CH: Oh man, they’re so good. It’s like 15 or 20 minutes of someone taking an incredibly dirty rug and cleaning it.

JW: Okay.

CH: It’s incredibly, incredibly relaxing and satisfying. So the point is that there are certain formulas for grabbing and holding attention. All of us in journalism work – we know about leads and we know about conflict and we know about the narrative arcs and characters and all the things that we learned to try to hold attention. But then there’s just innovation, right? People do different cool new things. And it turns out that the sort of human ingenuity still retains the ability to push out past what we thought were the frontiers of what people will pay attention to.

JW: Of course, as you say, Trump is the political figure who has most fully exploited the new rules of the attention age. First, he got himself in the gossip columns on Page Six, The New York Post, then he became a TV reality show host, then he became a candidate, but getting all the attention in the world does not seem to make him a happy man. Is that just him? Or is it something about what you call social attention?

CH: I think it’s both. I think that he has stumbled upon this insight about the import of attention, because of something deeply broken and sad within him. Something that’s irreparably broken and irreparably sad, which is a desire, a voracious desire, to be recognized, to be loved, frankly, to be loved. And one of the sick tricks that social attention on the internet particularly plays is it gives us a synthetic form of the thing that we most seek as human beings. What we really want as a human being is recognition, other humans to recognize us as human. That recognition forms the foundation for all of the relationships that are meaningful in our lives. Relationships with friends, with lovers, with people we work with, with collaborators, attention is necessary for that, but it’s not sufficient. And so the experience of attention from strangers, particularly in social settings online, gives us a taste of this recognition, but can never quite fulfill that taste, and creates this kind of compulsive addictive seeking of ever more of it. And you see that with Trump a hundred percent.

JW: One of the things that makes Trump unique in the attention economy is the way he courts negative attention. Political figures generally don’t do that. Doesn’t he want to be admired?

CH: Yes, but what he wants more than that is attention. So I think that the weird trick that he pulled off, when given the choice, again, I don’t think this is theorized or planned out, but the way he sort of threw his kind of feral instincts, found his way to, is that given the choice between negative attention or no attention, he will always take negative attention. It’s the old PT Barnum, “As long as you spell my name right.” I think Trump has even quoted that at different points in his life. “There’s no such thing as bad publicity,” that’s another cliche we use to basically get the same point across.

Most politicians are not like that. Most politicians would rather not have any attention than have negative attention. Most politicians, if they think there’s going to be a bad story about them, they want it not to come out. And that simple trick of understanding that attention is so powerful in our age, it so consumes everything else, that negative attention is more important than just not people paying attention to you. And Trump just had an instinct for that, Elon Musk I think has replicated it, that very few politicians have.

JW: Right after Trump was reelected, Bill Maher talked about quitting his show. He didn’t want to spend another four years paying attention to Trump. I imagine you can understand that feeling.

CH: Yeah. I mean, we have one life to live, and I’ve spent now a decade of it almost, which is a big chunk. And partly, to be honest, I think partly why I so enjoyed writing this book, and I’m so thrilled to have it out in the world and be speaking to you and other people about it, is that it’s given me a thing for me to put my attention on that is distinct from the insanity of the daily news cycle as it swirls around Donald Trump, to think more deeply, to read more deeply, to sort of work through arguments. And that has been so good for my mind and my soul. This has been my own weird sort of form of therapy.

JW: Even without Trump, it’s hard to think about that, but even without Trump, life in the attention age is, you say, “more anxious, more depressed, more isolated; we have fewer friends, we see them less, we struggle to read in depth, the political sphere is more polarized, the information atmosphere is more polluted”– these are all quotes from your book.

But there must be some way out of here. And there are ways to restore what you call our collective control over our own minds. If our attention is the most valuable thing we have, then we come to a foundational question that is harder to answer than we might like it to be. What do we want to pay attention to? This is something you’ve thought about a lot. You’ve written a book about it. A really compelling and wonderful book. What’s your answer?

CH: I mean, fundamentally, I think there’s sort of universal things. I want to pay attention to my wife, to my kids, to my family, my parents who I’m very lucky to have with us, I want to pay attention to my friends, I want to pay attention to my hobbies and endeavors and projects. I want to pay attention to cultivating my intellectual pursuits like reading and writing books and maybe writing some other projects and working on some other things I want to develop. I want to get better at playing guitar.

These are the things I really want to pay – and I want to pay attention to my job. I mean, when I’m working on my work, I feel honored and privileged to do the work. I think it’s important work, and I want to do the best possible job with it. And in all those moments, I want to put my focus on those things. I don’t want to feel that frittered away sense, that tug against my will, that sense of sort of weird shame, regret, a kind of foggy memory of what you just did with the last 20 minutes of your life, that’s the feeling I think we’re – I think we all experience this in different ways to different degrees, but that’s my answer to that question.

JW: You say, “We’re very likely to see the growth of a market for alternative attention products, sort of the way there’s been a market for natural food, for organic farming, for the neighborhood farmer’s market.” Tell us a little more about that.

CH: Yeah, I think that the food analogy is really interesting here because there’s a very similar parallel process in which the kind of full scale commercial global industrialization of food production and food sales in the country produced a backlash. It started with folks who were doing things very outside the “norm”. They were dropping out and going back to the land and they were starting farms and they were starting organic farms; they were starting natural food stores. And all of this was kind of fringe and kind of weird and hippie. But it turned out that those critiques grew in their force as more and more people came around to feeling the same way about the industrial food processes. And this entire alternate food culture, food ecosystem, and food economy was built out of that initial rebellion. And I think we’re going to have the same with our digital culture.

One way to think about this too is that we used to just have a lot more non-commercial spaces online. They’ve all been completely taken over by commercial spaces, the platforms. But actually the internet that I kind of first came to love was a largely non-commercial internet. It was an internet in which people could connect to each other through open protocols that were facilitated in a non-commercial cooperative setting. And it wasn’t to say there was no commerce online, there was tons. Local businesses had their advertisements there, there was a bunch of stuff. But the fundamental networks of connection were not owned by anyone. In fact, that was part of the kind of utopian vision of this version of the non-commercial internet. And the fact that it was built once before means that it genuinely can be built again, in the same way that in physical life we moved between public and private spaces, between commercial spaces and non-commercial spaces all the time.

The sidewalk is a non-commercial space. The store is a commercial space. The park is a non-commercial space. The internet increasingly is just living inside a mall. We don’t have actual non-commercial public spaces in which there aren’t people with a monetary incentive to extract our attention as the means by which they will make a profit. We have that in physical life, even hyper-capitalist American society. We do have non-commercial spaces. So that’s another way that I think we’ll see that. And then I think we’re going to start to see much more forcible regulation of attention and the platforms.

JW: And what would that look like, regulating the market for our attention?

CH: So one place we’re seeing it is with children. We’re seeing attempts to regulate the age minimums for kids online. And that’s a very contested policy area. There’s people on the left who think it’s a bad idea, particularly because of teenagers and young teenagers having access to information about human sexuality, particularly not heteronormative forms of that for folks that are queer and trans. And I totally understand those concerns. I don’t think they’re ridiculous.

The principle that we shouldn’t be monetizing the attention of minors to me just seems obviously true. The question of how we implement that – and to be honest, part of the critiques you see from the left of some of these legislation has to do with the fact that because the non-commercial internet has become so desiccated, because the only place that exists for all kinds of information are commercial attention markets and the platforms, that the two sort of work hand in hand. It’s like, ‘Well, the only way to get information if I am trans or queer and I’m sort of starting to learn about myself is through the platforms,’ which is a perfectly legitimate argument I think to make at this point, but that speaks to the poverty of these non-commercial alternatives that we really have to build. In fact, rebuild, because they once existed.

JW: You end your book by saying that for the attention economy, we need something like the slogan of the campaign for the eight-hour workday. What was that slogan?

CH: It was, “Eight hours of rest, eight hours of work, eight hours for what we will.” And I think that “what we will” is so profound. It’s so beautiful. What we will. What do we want to do with our lives in the third of the day that we’re not sleeping and we’re not working?

JW: Eight hours for what we will. Chris Hayes – his new book is The Sirens’ Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource. It’s really important and really good. Chris, thanks for everything you do, and thanks for talking with us today.

CH: Jon, thanks. That was great.

[BREAK]

Jon Wiener: Now it’s time for Your Minnesota Moment: News from my home town of St. Paul that you won’t get from Sean Hannity.

Stephen Miller, now White House chief of staff, has threatened to prosecute officials in 12 Minnesota counties for failing to cooperate with Trump’s deportation policies. The counties include not only those in the Twin Cities area, around St. Paul and Minneapolis, but also eight other counties that are mostly rural farming areas and mostly voted for Trump, all of which refuse to keep undocumented people in jail after they have completed serving their terms so that federal agents could pick them up for deportation.

The sanctuary places Stephen Miller has threatened include Winona, a river town on the Mississippi from the 1850s; Winona Ryder was named after the town and grew up nearby.

Also the town of Wilmar, in Western Minnesota, where the Willmar Eight made history –

eight women who worked for the Citizens National Bank in Willmar, who went on strike in December, 1977 protesting against sex discrimination in hiring and promotion. The eight picketed the bank through the coldest days of winter, dividing the town of 14,000. Their story was turned into a documentary called “The Wilmar 8,” directed by Lee Grant.

Another sanctuary jurisdiction targeted by Stephen Miller is Pipestone, out by the South Dakota border, home of Pipestone National Monument, where Indigenous people have quarried the local red stone for over 3,000 years o make pipes used in prayer and ceremony – a tradition that continues to this day, and makes this site sacred to many people.

Before Trump officially took office, Stephen Miller’s organization, America First Legal, sent letters warning the officials they could face prosecution and sent to prison if they failed to detain immigrants for ICE. The letter said quote “We have identified your jurisdiction as a sanctuary jurisdiction that is violating federal law. Such lawlessness subjects you and your subordinates

to significant risk of criminal and civil liability. Accordingly, we are sending this letter to put you on notice of this risk and insist that you comply with our nation’s laws.”

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison joined his counterparts in 11 other states targeted by Stephen Miller, including California, which have sent a joint statement that says quote “It is well-established — through longstanding Supreme Court precedent — that the U.S. Constitution prevents the federal government from commandeering states to enforce federal laws. While the federal government may use its own resources for federal immigration enforcement, the court has ruled that the federal government cannot ‘impress into its service — and at no cost to itself — the police officers of the 50 States.’”

The state attorney generals; statement also said “this balance of power between the federal government and state governments is a touchstone of our American system of federalism.”

The first Trump administration threatened to take federal money from states – mainly funds for local police, from counties and cities that they deemed “sanctuaries” for undocumented immigrants. But – after a string of lawsuits – virtually all those efforts failed.

Now Trump is trying again to withhold money from “sanctuary” jurisdictions through an executive order he signed last week. A federal judge in San Francisco promptly blocked the order nationwide, declaring it was unconstitutional.

Trump now has upped the ante with threats to prosecute officials in sanctuary jurisdictions.

The courts are likely to prevent those prosecutions.

This has been Your Minnesota Moment, news from my home town of St. Paul – a special feature of this broadcast.

Subscribe to The Nation to Support all of our podcasts

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation