Reasons for Hope From Iowa Republicans, Plus American Fiction

Reasons for Hope From Iowa Republicans, Plus “American Fiction”

On this episode of Start Making Sense, John Nichols analyzes Monday’s GOP caucus results, and John Powers reviews the new film starring Jeffrey Wright.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

John Nichols reports on Monday’s Republican caucuses in Iowa, and explains why Iowa is the state with the biggest shift from blue to red between Obama in 2008 and Trump in 2020.

Also: The new film "American Fiction," starring Jeffrey Wright, takes up the question, do Black writers have to "write Black"? The film is based on the novel "Erasure" by Percival Everett, which is considerably wilder and more uncompromising than the film. John Powers comments—he’s critic at Large on NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

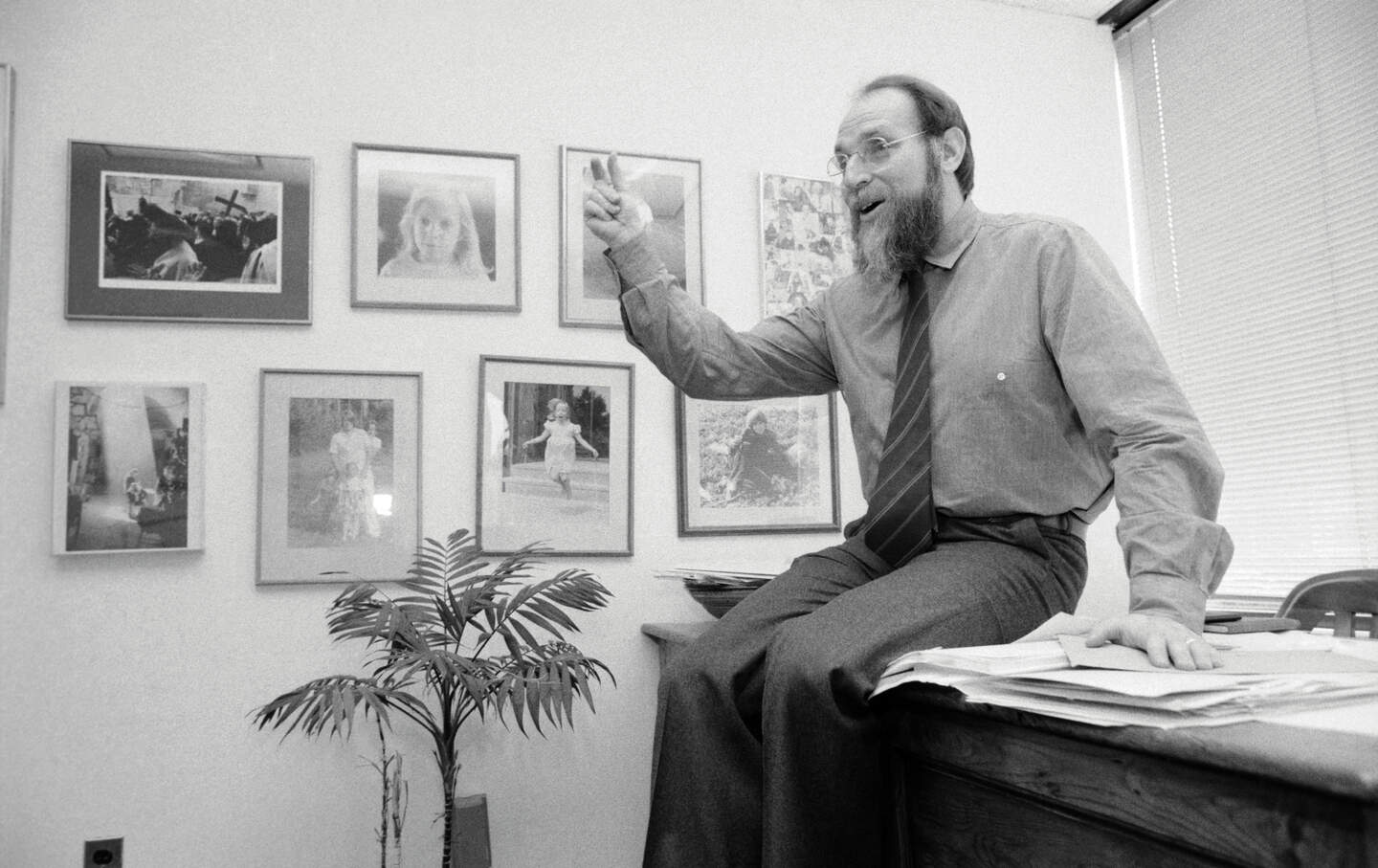

Jeffrey Wright in American Fiction.

(Photo by Claire Folger)On this episode of Start Making Sense, John Nichols reports on Monday’s Republican caucuses in Iowa, where 31 percent of Republicans said they’d consider Trump unfit for the presidency if he were to be if he were to be convicted of a crime

Also on this episode: The new film American Fiction, starring Jeffrey Wright, takes up the question, do Black writers have to “write Black”? The film is based on the novel Erasur by Percival Everett, which is considerably wilder and more uncompromising than the film. John Powers comments—he’s critic at Large on NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Ths coming Friday is the deadline for the Justice Department to turn over the Epstein files to Congress. But we already know the key fact about Epstein’s famous friends–they didn’t care that he had hired a 14-year-old girl for sex—and gone to jail for it. But why was that? Katha Pollitt comments.

Also: the hidden politics of the New York Times crossword puzzle: Natan Last explains; his new book is Across the Universe: the Past, Present, and Future of the Crossword Puzzle.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Jon Wiener: From The Nation magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the show: a new film about a Black writer who is told his work is “not Black enough.” It’s the movie American Fiction, starring Jeffrey Wright. John Powers will comment – he’s critic at large on Fresh Air with Terry Gross.

But first, reasons for hope – from Iowa Republicans. John Nichols will report – in a minute.

[BREAK]

Maybe you heard the news: Iowa Republicans met in caucuses on Monday. 51% voted for Donald Trump as their 2024 presidential candidate, 21% voted for Ron DeSantis, and 19% for Nikki Haley. John Nichols was there. Of course, he’s national affairs correspondent for The Nation, author of many books, most recently, It’s OK to Be Angry About Capitalism, co-authored by Bernie Sanders. John, welcome back.

John Nichols: It’s good to be with you, my friend.

JW: The New York Times called it “Donald Trump’s Triumph.” Nevertheless, you found reasons for hope – in the entrance polls.

JN: That is true, my friend. And at caucuses, you don’t do an exit poll, you do an entrance poll because they’ve got to get people going in, because caucuses are long affairs and people don’t leave all at the same time. But also, there’s a subtlety to it, our media desperately wants to make predictions about turnout and results and things like that, and so they do the entrance polls. And unfortunately, the entrance polls tend to get tossed aside as soon as they get the top line that tells you who they think is going to win, in this case being Trump. But I found this entrance poll fascinating, because in the midst of it, they asked, “If Donald Trump is convicted,” didn’t ask about the charges and all that, they said, “If he’s convicted, would he be unfit for office?” And 32% of the Republicans who came out, in communities where sometimes the windshield was 45 degrees below zero, so these are pretty motivated folks, 32% of them said that Trump would be unfit. That’s a striking figure.

And I’ll say one other thing about it that’s important. I’m not naive, I know that there are plenty of Republicans who would vote for an unfit candidate if that candidate had an R after their name. But what I am telling you is, if you’ve got a third of people participating in the Iowa Republican caucuses saying a convicted Trump would be unfit for office, that’s a red flag, that’s a significant number, and it fits with a number of national polls as well. So I think that’s something we ought to be focusing on, at least as much as we do the fact that Donald Trump got a bunch of Iowans to vote for him yesterday.

JW: About 115,000 people showed up for these, this is a state with – what? More than a million and a half voters, or something like that. So you’re right, these are the most committed, most passionate Republicans, and if almost a third of them say he’d be unfit to serve, we do have a significant reason for hope here.

51% voted for Donald Trump. I don’t know. Is that a triumph? Half of Republicans say they’d rather have somebody else. I guess it’s a triumph compared to 2016 when he lost to the man he called, “lyin’ Ted Cruz.” At that point, you will recall Trump claimed fraud and demanded that the Iowa Republican Party nullify the results and do it over. They refused. So compared to that, this Monday was a triumph, but does this mean that the Republican primary season is over and we don’t have to do this on Wednesday mornings from now on?

JN: Well, we may have to do a few Wednesday mornings before it’s done, but let’s put a few things in perspective. Number one, yeah, winning half the vote in a caucus as the immediate former Republican President of the United States, and the front-runner in the race, by any measure, the guy who literally is in the news every day and thus is identified, whether you like him or not, as the biggest known Republican, is not overwhelming, especially when you’re running against Ron DeSantis, who, by the nature of the game, turns people off every time he meets them.

I don’t think it was all that impressive at finish. It was a credible finish, he won, give him that, but he won 98 of 99 counties. So he did have a broad sweep in urban, rural, and suburban areas, and give him that. But what was notable was that in the more suburban areas, Nikki Haley really did show strength. DeSantis came in second, Haley a very close third. That’s going to be very significant next week in New Hampshire, because New Hampshire, the Republican base there is very much dominated in the southern part of New Hampshire in very suburban areas. And so, you’ve got a different dynamic politically in New Hampshire, and Haley has been, in some polls, closing the gap.

So I think that New Hampshire’s the real test, New Hampshire’s going to be the place where it’s make or break. If Trump wins New Hampshire big, then I think we can say this is pretty much over. He’s going to be the nominee, like him or not. On the other hand, if Haley were to beat him in New Hampshire, then you combine that with these numbers we’re talking about, a third of voters say unfit if he’s convicted, then suddenly that churn, that discomfort with a possibly convicted Donald Trump, becomes a real factor in the Republican race. I don’t think it defeats him, but I do think it keeps that race going for a good deal longer.

JW: There’s a deeper question about Iowa that I’d like to talk to you about, its political transformation over the past couple of decades. Iowa used to be a Democratic state. No state in the nation has swung as heavily Republican between 2012 and 2020 as Iowa. In 2012, Obama carried Iowa by six points. In 2020, Trump carried Iowa by eight points. So that’s a 14-point difference between Obama in 2012 and Trump in 2020, bigger than any other state. Do you have a theory to explain this?

JN: Sure, a couple of theories. And first off, I’m going to take you through a quiz, Jon, are you ready?

JW: I’ll try.

JN: All right. Who won California in 1988?

JW: 1988? I cannot remember.

JN: George H.W. Bush. Who won Vermont in 1988?

JW: I do not know.

JN: George H.W. Bush, Republican nominee. Who won West Virginia in 1988?

JW: I give up.

JN: Michael Dukakis, the Democrat.

JW: How could I forget Dukakis?

JN: My point is that states change. California can go from backing the Republican nominee for President in 1988 to being what it is today, which is basically a two-thirds Democratic state. These changes are a part of our political dynamic.

JW: Yeah.

JN: And then you ask, okay, is there something anomalous about Iowa? Is it a unique dynamic? It does relate to something that you and I have talked about a little bit in the past. Rural America has felt extremely left out of our politics for a long time. Iowa is not an entirely rural state, but it has a very substantial rural population, its rural counties are still quite dominant in Republican politics especially. It used to be that Democrats could hold their own in rural areas, because they had a rural strategy, they had candidates like Tom Harkin and others who could talk rural, frankly, for lack of a better term, and connect on the issues, and you could be quite liberal and still be in touch.

That’s fallen apart in Iowa, and frankly it’s fallen apart in North Dakota, which was a state that sent Democrats to the US Senate until very recently, it’s been weakened in my own state of Wisconsin, and others. The Democratic Party has got to be able to talk to rural America. If it does, then you’re going to see some claw back into a place like Iowa. You’re also going to see Democrats win in places like Montana, where Jon Tester is holding on, and maybe, again, in places like North Dakota. You cannot get people’s votes unless you talk to them, and I don’t think Democrats do enough talking to rural folks.

JW: I studied this a little bit – the cities of Iowa remain Democratic. Of the nine largest counties in Iowa, only one switched from Obama to Trump. It’s the other places that you’re talking about that really make the difference. And there has been a significant economic decline. Iowa, it’s not exactly a Rust Belt state, it doesn’t have steel mills, but it does have a lot of smaller cities and towns that had factories, and those have disappeared in the last couple of decades.

JN: And you’ve seen also, this is a big thing, and I know that – why do we end talking about antitrust laws with Iowa? Well, antitrust is a huge deal for Iowa, because you’ve seen the agribusiness come in there and take overwhelming control of farm country, and of the economies in small towns and rural areas. And so, there’s plenty where Democrats could talk about these issues. I always remind people that in 1984 and 1988, Jesse Jackson competed in Iowa, and he didn’t win, but he did pretty well, he got some traction there, because he went out to rural areas and he talked to farmers, and they were like, ‘Oh, okay, I get it.’ And in the fall of 1988, Dukakis won Iowa as a Democrat talking about farm issues. And so, this can be done, but it hasn’t been done in a long time.

At this point, I doubt that Iowa is going to be a competitive state this fall. I think that Trump is very likely to prevail there. But if the Democratic Party was smart, what they would do is begin that rebuilding process. It’s the old Howard Dean 50-state strategy, and a part of a 50-state strategy is to have a really smart approach to rural issues. At this point, I don’t think Democrats have begun to talk enough about those issues.

JW: Going back to the campaign that just ended there, I was astounded by the amount of money spent on TV ads. My friends who live in Iowa City say the best thing about the Republican caucuses is it’s the end of the TV ads. They were drowned in negative ads, $123 million spent on attack ads, basically DeSantis and Haley attacking each other. Tricky Nikki versus DeSantis, too weak to lead. If you take $123 million, divide it by the 115,000 people who voted, I think you get something like $1,000 dollars per vote spent on primary ads. Is my arithmetic right here?

JN: Yeah, Iowa was flooded with TV ads, and I strongly disagree with you about being excited those ads are done. I will tell you, there is nothing more fun than watching Ron DeSantis find out ways to pick on Nikki Haley, and vice versa, and stuff like that. And this year was pretty good in this regard, although I will never ever forget a couple of years back when the Iowa caucuses were just the week after Christmas, they had them very early in January, and the candidates had to figure out how to integrate Christmas into their attack ads, and they did it.

The amount of money spent on TV advertising in Iowa completely obliterates the argument for Iowa as a starting point for the process. The whole theory on Iowa as a starting point for the process is that it’s grassroots, right? That it’s you meet with people in their living rooms, you talk to them, you talk deep on the issues, et cetera. And that just doesn’t happen in Iowa anymore. In fact, I was in Dubuque yesterday, and I was astounded. I’ve been in Dubuque on caucus days in the past, even really cold months, and there are signs out, there are headquarters open, there’s all this energy that you feel on the street. It wasn’t there this year because these campaigns have poured all their money into television, and a little bit into radio on that.

And I will tell you, there’s no argument for an Iowa caucus if it’s a TV caucus. There are pretty good arguments for changing the way that nominations are done anyway. But I found it dispiriting and frustrating, and frankly, I think it’s actually a part of why, one of the many parts, along with 45-degree below zero windchill, why the turnout was lower. Iowa had the lowest caucus turnout this year on the Republican side in almost a quarter-century. And so, people weren’t energized or excited by all those ads, I think they were actually put off by it.

JW: You reminded us that we have New Hampshire coming up, the first place everybody gets to vote, and I understand in New Hampshire, Democrats and Independents can vote for a Republican candidate.

JN: They’ve got to jump through a couple of hoops – you got to re-register and stuff like that, but yes, there are some avenues by which it can be done. And fascinatingly enough, a candidate who’s gotten out of the race, Chris Christie, actually made a major play for Democrats and Independents. He had a whole campaign or a PAC supporting him saying, “Re-register so you can vote for Chris Christie and stop Donald Trump in the primary.” And Christie’s out now, but I think the evidence from Iowa is that a decent number of folks may well do that, and you may see some crossover to vote in that Republican primary, probably at this point for Nikki Haley, even though a more undeserving candidate you could not find. She’s anti-labor, she’s extremely right-wing, blah, blah, blah, but she’s become this alternative to Trump.

JW: Because she doesn’t want to rerun the 2020 election and declare Trump president.

JN: Yeah, our baseline standard. Although by the way, she does say that she’d vote for Trump if he’s the nominee.

JW: Yeah.

JN: And also talks about pardoning him. But the interesting thing about New Hampshire is that it will have both a Republican and a Democratic primary. And I wrote a big piece for The Nation on the Democratic side. That’s a danger zone for Joe Biden, because if Joe Biden loses, say, a third of the primary vote to Marianne Williamson, Dean Phillips, other candidates, maybe write in, there’s a campaign out there to write in ‘Ceasefire Now’ on Gaza, if a substantial portion of people who come to cast ballots in that Democratic primary don’t vote for Joe Biden, that’s going to be an alarm bell as well.

One of the realities of the 2020 campaign is that we do face the prospect of having two candidates nominated by the two parties who are not beloved, particularly by on either side. So we’re watching these primaries and caucuses, these early races, to get a feel for how much disenchantment there is, how much frustration there is. In Iowa, we found half the people didn’t vote for Donald Trump. That’s a very significant number, you take that, and you put that in the mix. We’ll look at New Hampshire and we’ll see similarly, if there is a significant slippage on the Democratic side? And so, I do think we’re in the most important season, in many ways, of the presidential year, because this is where we get a sense of where everything going forward stands. Iowa told us a lot, I will emphasize, I think both on the Republican side, and to some extent, the Democratic side, New Hampshire will tell us even more.

JW: Our big takeaway today, 31% of Iowa Republicans say they’d consider Trump unfit for the presidency if he were to be convicted of a crime. John Nichols, read him at thenation.com. Thank you, John, for giving us reasons for hope – from Iowa Republicans.

JN: I think the Iowa Republicans really want you to be hopeful.

JW: [Laughter] We’ll talk to you again the day after New Hampshire.

JN: I look forward to it, brother. It should be interesting.

[BREAK]

JW: Not Black enough: that’s the issue taken up in the award-winning new film, American Fiction, starring Jeffrey Wright as a frustrated Black novelist. For comment, we turn to John Powers. He’s critic-at-large on the NPR show, Fresh Air with Terry Gross, where he is heard by more than 8 million listeners on the radio and the podcast. He’s worked for 25 years as a critic and columnist, first for the LA Weekly, then Vogue. His work has also appeared in The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Nation. Last time he was here, we talked about Slow Horses, the Mick Herron spy stories that have been turned into a series on Netflix. John Powers, welcome back.

John Powers: Glad to be here, Jon.

JW: American Fiction, the film about an unsuccessful Black writer, is based on a 2001 novel called Erasure, written by Percival Everett, who is a Black writer and a very successful one. An award winner, he’s written something like 15 novels. We talked here about one of them, The Trees, revisiting the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955 in Money, Mississippi. That novel was shortlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize. The book that’s the basis of the film American Fiction, Erasure, has been called a dark comedy, but it’s a lot more than that. It’s an amazing book about something serious, publishing Black writers. It’s merciless as a satire. It’s also formally clever and bold. Tell us about the novel that’s the basis of the film American Fiction.

JP: The novel Erasure came out in 2001, and I would preface it by saying that when it was written, at that point, Percival Everett had published several novels that were considered to be quite weird: the retelling of Greek myths, for instance, and academic parody novels. In fact, he was doing stuff that wasn’t officially considered to be “Black.” Clearly, this got to him, so he wrote in Erasure a novel about an unsuccessful writer, like himself in that respect, who is tired of being unsuccessful and is horrified to discover that he’s being told to write “Blacker.” When he looks in the world, to see what that means at that point in 2001, which would be the world of books like Precious by Sapphire, and in Hollywood terms, films like Boyz n the Hood.

Also, there’s Richard Wright’s Native Son in the background, which is basically, he realizes that when people want you to write “Black.” They want you to write about the ghetto. In fact, in the book there is a “We’s Lives In Da Ghetto,” which is a bestseller that we see parts of, and that the hero Thelonious Monk Ellison views with great contempt. The major plot point here is that he decides in frustration to write a savage parody of it called “My Pafology,” spelled with an F, P-A-F-O-L-O-G-Y, but that is basically a parody of that kind of novel. Much to his horror and surprise and maybe a little delight, it is taken up and becomes a literary sensation. This is the one successful book he’s ever written, which is the book he wrote with total contempt for the audience and the thing that he’s writing.

Surrounding that is the story of his relationship to his family. He is from an upper middle-class Black family. His father was a doctor, his brother and sister are both doctors. He’s the oddball out ’cause he’s the writer, and his mother is suffering from Alzheimer’s. So you intercut between those two stories, his writing story and his family story, and then because Percival Everett never writes a simple book, there are also imaginary conversations between people. There are book reviews in The New York Times. There’s the curriculum vitae of Monk Ellison. There are parodies within parodies, and the story gets wilder and crazier shot through with hilarity and anger.

JW: Yeah, my favorite part of the things that are included in the novel, there’s the complete novel written by our character –

JP: Yes, it’s a full parody novel.

JW: “My Pafology”– six chapters of ghetto talk. I’m glad you mentioned that the novel Erasure also includes the CV and publishing list of our protagonist, because he has an MFA in writing from UC Irvine, which is just downstairs from my office.

JP: I know. It’s absolutely –

JW: Definitely a sign of talent. Turning this ruthless literary and political satire and these formal experiments into a movie is a big challenge, especially for a young first-time director, Cord Jefferson.

JP: Yes. Cord Jefferson had a successful career writing TV shows, things like Succession, I mean very successful. But, of course, here he’s doing something which is exceedingly hard, if I can put it in this way, taking a novelist that might’ve been written if Godard had written novels, a Godardian novel and transforming it into a Hollywood movie that would make sense to a mass audience. So that’s an exceedingly difficult thing to do for starters. Then, in addition to all of that, the world has changed in the 22 years since Percival Everett had written the book. One of the things that had changed is that Black writing is not treated in the same way now as it was 21 years ago when he made it so that Cord Jefferson couldn’t just make this a ruthless satire of how Black writers never get published unless they write obvious ghetto-type stuff, ’cause that’s simply no longer the case.

So in adapting this incredibly complicated, angry novel for a mass audience, what he’s done is he’s simplified it. For example, you no longer get the huge 70 pages of parody of the ghetto novel. You get one scene very wittily staged, I think in the film, of him writing the novel, you get a sense of it. But everything is played down except for the family story, which I think is made to occupy more of the book, and that’s partly for two reasons. You get the film script partly ’cause it’s more sentimental, and I think that the general vision of the film is softer than the book, but also because part of what this book does that Everett does as well as many other things, is wanting to juxtapose the world of the writer and the crazy ghetto fiction with the actuality of middle-class Black life. This film, I think, perhaps overdoes that a little bit, wanting to move us a lot with the story of the mother’s Alzheimer’s and all the rest of it, which seems more generic, I think, in the film than it does in the book.

JW: I want to go back to the scene you mentioned how Cord Jefferson deals with the gigantic section of the novel that is the ghetto satire that our protagonist Monk Ellison writes. Normally the way this is treated in the Hollywood movie is the writer sits at the typewriter and bangs away. Cord Jefferson has a much more creative and pretty successful way of showing what it is that Monk Ellison writes. Tell us a little more about this.

JP: Well, he’s writing, but the action is all in the room with him so that he’s interacting with what he’s writing and it’s taking place, so it’s not separate. You don’t cut from him and then cut away to a scene from the book. The writing and the scene coexist in the same space, which is probably, in some ways, the closest thing to the spirit of Percival Everett in the entire thing, which is, you have the multiple layers of things working at the same time coexisting in the same space. It’s a good scene and you do very quickly get, in film terms, you register the kind of novel that it is because in film terms as opposed to book terms, a little goes a long way. So that’s exceedingly well done.

JW: One other thing about the scene where Thelonious Monk Ellison is writing the novel and two characters are acting it out as he’s writing: the characters interrupt the scene to complain to him, “This doesn’t sound right. You can do better than this”–which it’s a nice, what do we call it? Postmodern touch.

JP: It is, and there’s a great Irish novel by Flann O’Brien where the characters start taking over the book from the writer. It is a classic modernist thing.

JW: You mentioned that one of the problems that Cord Jefferson faced is that things have changed for Black writers in the what, 23 years since Percival Elliot first published this. Not everybody agrees with that. Pamela Paul, who was the editor of The New York Times book review until a year or two ago wrote about this, and she says although Erasure came out in 2001, quote, “the mindset it describes feels even more pervasive in 2023.” I guess you don’t agree with that.

JP: Well, she’s talking from inside the publishing industry, and it may well be the case. I simply say in relation – for my reviews I get sent lots of books, I can tell you that, just over the 20 years, the range of books by African American writers that are sent to me has expanded hugely. Certainly, critics do things like they now review them. Because I think one of the strange things probably for Percival Everett is you’re writing these really interesting smart books in the ’80s and ’90s, and they barely get noticed because you’re doing something weird, and nobody wants to read about it. So I think it’s more open and abstract. I’m certainly not suggesting everything is great. Even the film itself seems like it has to play things a little safer than you would if you were – maybe a comparable adaptation of a novel by a white writer about white people might actually be able to be more daring than this adaptation. But it feels to me that it softens it in a way to make it more acceptable and accessible.

JW: Percival Everett has written 15 novels. Let’s note that the one that was shortlisted for the Booker is about the lynching of a 14-year-old Black boy-

JP: Oh, yes.

JW: In Mississippi.

JP: Oh, yes. No. An interesting, weird side effect of this book when he wrote it was he was a writer who basically only a small number of people knew about this book, put him on the map. In fact, he got put on the map by writing the book about how you can’t get on the map unless you write a book that’s unlike, and he became a literary star from this book, but it’s a great book. I should also say that it’s not like he somehow lucked out and became it, and he wrote the book that hit the moment and it still resonates. It resonates truly because we also realized that if you’re an African American artist in a certain kind of way, you will always be more successful and more in demand if you do a certain kind of thing.

If I can just parenthetically say it’s interesting that Colson Whitehead, who was writing wonderful books, an admired writer who got good reviews but never really sold or got all that much attention until he wrote Underground Railroad, and all of a sudden, he’s writing about slavery, which is the kind of thing he pointedly was trying not to do originally. I don’t think he did that as a commercial effort. I thought he was pushing himself thinking, ‘Oh, this is the kind of thing I don’t like to write about. I should probably write about it ’cause it’s scary and hard.’ So I respect it, but that’s the one that took off because still, I think most audiences, if it’s a Black writer, will feel happier if they’re writing about slavery than in his case, writing about growing up as a privileged Black kid in Sag Harbor.

JW: Yes. Let’s talk for a minute about Jeffrey Wright. I think most of us discovered him in the HBO Angels in America, and we saw him recently in Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City, where he was the general who hosts the convention of the –

JP: And it’s fantastic.

JW: Of the genius kids. I see he’s also been in three James Bond films and one Batman and lots of TV including Boardwalk Empire. So he’s done a lot, and he’s very well respected, but people are saying this is the best thing he’s ever done.

JP: I don’t know if it’s the best thing he’s ever done. I think this is the chance for him to do a lot more of what he normally does. He’s been a fantastic actor, what, for 20 years or more than 20 years? He’s been fantastic ever since I saw him. But he rarely gets the kind of role where he gets to be the center of a movie showing a whole different range of things. Usually, he is like the fantastic supporting actor. In the James Bond things, he’s Felix Leiter. He’s showing up as the friend, and in fact, you’re always happy to see him ’cause he’ll be good.

JW: Some reviewers have complained about this movie that there are really two separate films here, the sharp comedy about publishing and the drama about family problems. One critic wrote, “Not only do the two films barely meet, they often feel in competition with each other.” I wonder if you agree with that.

JP: I don’t feel that they’re in competition with each other. I think they don’t merge together perfectly, and depending on which one you prefer, I can imagine being less happy with the other one. So I enjoy more the satirical harder edged side, and the family side seems more generic to me, maybe because we’ve seen lots of movies about families and the dad committed suicide and the mom has Alzheimer’s, that feels familiar. It’s less familiar with African American stuff.

I think Cord Jefferson, who’s a very smart guy, clearly wants to juxtapose the down-to-earth reality of that life where there are family problems; people are sad, the brother thinks he’s secretly gay and everybody knows he’s gay, there’s that, with the wild comedy because you’re showing, oh, that there actually is an ordinary Black world that’s distinct from both the crazy ghetto stuff, but also from the crazy academic thing because Monk Ellison is a weirdo, and he knows he’s a weirdo. He’s an angry weirdo who doesn’t quite fit into his family properly. Watching it myself, I got a little bored with the family stuff. I thought there was too much of that, and I think it also softens things a little bit. For me, the most telling detail, his sister dies. How does she die in the film?

JW: In the film, she dies of a heart attack at a restaurant where they were having dinner. In the book, she’s a doctor at an abortion clinic and she gets murdered by an anti-abortion activist.

JP: Part of the book’s anger is that sort of thing, the craziness and stupidity of, in some ways, maybe the most virtuous person in the entire book killed by an anti-abortion activist. When you take that out and she just dies of a heart attack, that’s a sentimental touch. I think with the family stuff, it tends to go more there, and I would’ve preferred it if they had kept it with more teeth to it.

JW: The novel Erasure is fierce, uncompromising, and wild. The movie American Fiction is funny and warm. My suggestion is see the movie and read the book.

JP: I agree with you completely. I think in a strange way, it’s one of those things where it’s interesting to do them side-by-side because you won’t regret reading the book, because the book’s great. I think the movie’s pretty good, and you won’t regret seeing it. It actually goes by very well. It’s really well acted. Jeffrey Wright’s great. It’s funny. It’s a good movie that’s better than some of the movies that are getting more awards, and it has a funny opening sequence making fun of a “woke white student,” and it’s filled with great stuff. It’s just that the book’s a landmark. One of the ways it’s a landmark is that it’s a tricky, complicated, impossible to summarize and to film book. He’s an experimental writer, and it’s not an experimental film.

JW: John Powers is critic-at-large on Fresh Air with Terry Gross. John, thanks for talking with us today.

JP: My pleasure.

Subscribe to The Nation to Support all of our podcasts

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation