White Voters and Joe Biden; Harriet Tubman and History

On this episode of Start Making Sense, Steve Phillips critiques Democratic campaign strategy, and Tiya Miles talks about her new book, Night Flyer.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

What should the Democrats do about white voters? Most of them have voted for Trump, twice. How much of that can be changed? Steve Phillips reports on new research that should reshape Democratic strategy.

Also: Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery and returned again and again to lead others north to freedom. Now her story is being told in a wonderful new book, with the wonderful title “Night Flyer.” the author is Harvard historian Tiya Miles; she joins us on the podcast.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

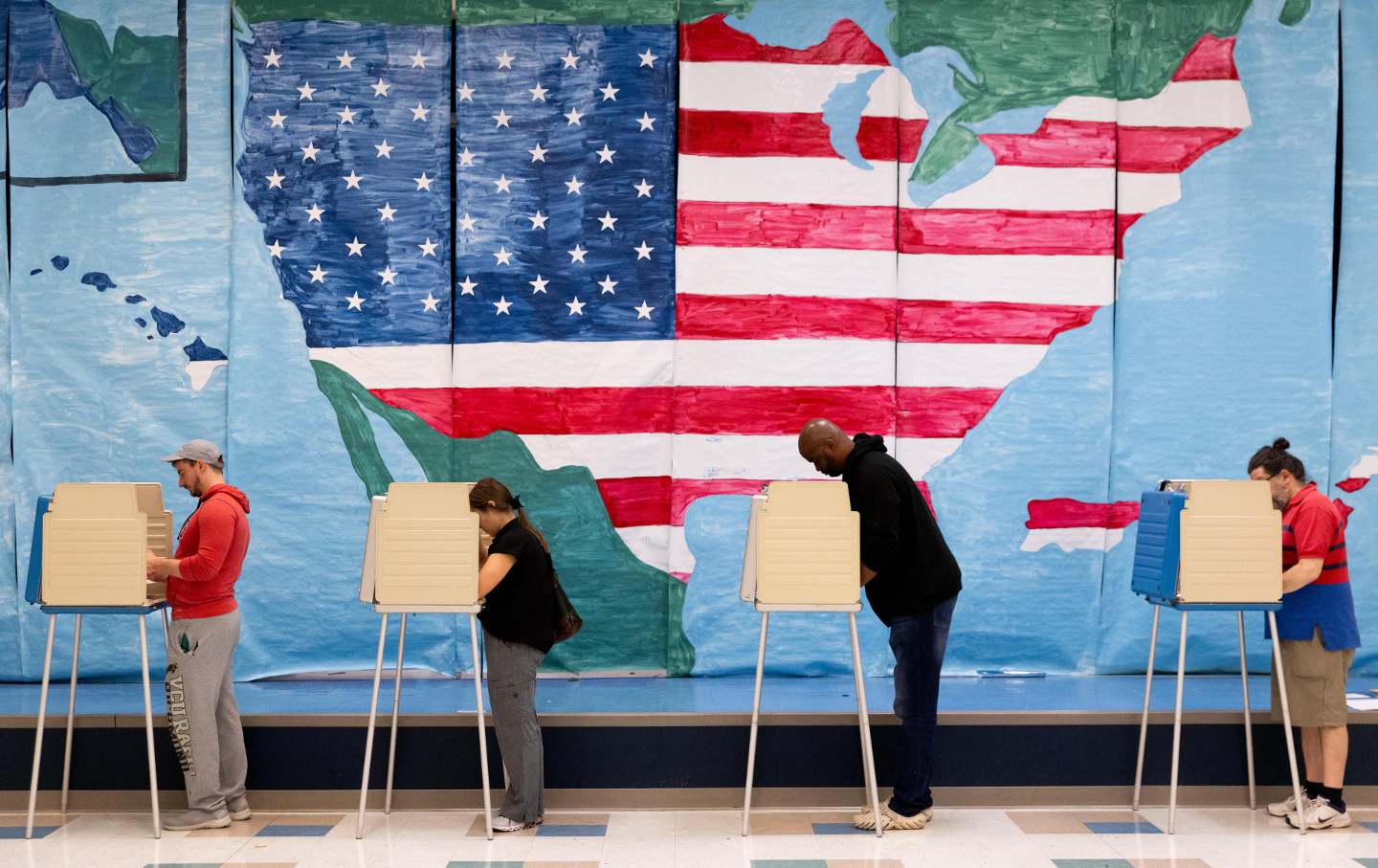

Voters at a polling station in Midlothian, Virginia, November 7, 2022.

(Julia Nikhinson / for the Washington Post via Getty Images)What should the Democrats do about white voters? Most of them have voted for Trump, twice. How much of that can be changed? Steve Phillips reports on new research that should reshape Democratic strategy.

Also on this episode of Start Making Sense: Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery and returned again and again to lead others north to freedom. Now her story is being told in a wonderful new book, with the wonderful title Night Flyer. The author is Harvard historian Tiya Miles; she joins us on the podcast.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Republicans are about to end Obamcare subsidies, driving up premiums for 20 million people during the year of the midterm elections. How have they managed to end up after all these years with no health insurance plan of their own? John Nichols comments.

Also: Bob Dylan’s earliest recordings have just been released—the first is from 1956 when he was 15 years old—on the 8-CD set ‘Through the Open Window: The Bootleg Series vol. 18” – which ends in 1963, with his historic performance at Carnegie Hall. Sean Wilentz explains – he wrote the 120 page book that accompanies the release.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Jon Wiener: From The Nation magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the show: Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery and returned again and again to lead others north to freedom. Now her story is being told in a wonderful new book, with the wonderful title “Night Flyer.” The author is Harvard historian Tiya Miles. We’ll speak with her, later in the show. But first: can the Democrats win enough white voters to reelect Joe Biden? Steve Phillips will comment — in a minute.

[BREAK]

What should the Democrats do about white voters? Most of them voted for Trump, twice. How much of that can be changed? For comment and analysis, we turn to Steve Phillips. He wrote the bestseller, Brown Is the New White: How the Demographic Revolution Has Created a New American Majority. He also hosts the podcast Democracy in Color, and he writes for The Guardian, The Washington Post and The Nation. A new updated edition of his book, How We Win the Civil War, is out now. Steve Phillips, welcome back.

Steve Phillips: Thanks for having me. Glad to be here.

JW: A lot of us had hoped that Trump’s new status as a convicted felon would lead at least some of his supporters to abandon him, but mostly that does not seem to have been the case. Does that surprise you?

SP: No, fundamentally it doesn’t. I mean, the hypocrisy is notable in terms of how fundamental support for law and order and whenever it was people of color on trial, then it’s like, “Well, country of laws. Law and order. Don’t defund the police,” right? So now that it’s Trump, all that’s turned on its head, but the lack of intellectual, logical, moral consistency is not surprising. And most fundamentally, the essence of Trump’s appeal has always been he’s the champion of whiteness and of the notion that this is fundamentally a white country, and so everything else becomes secondary. I titled the intro to my book, How We Win the Civil War: A Choice Between Democracy and Whiteness, which is exactly what January 6th was. We had a democratic election, which every governor, including Republican that signed off on – and we could accept that, or we could try to overthrow it. And we saw what happened on January 6th.

JW: A few statistics: about 40% of white voters voted for Biden four years ago. About 37% of white voters voted for Hillary in 2016. How different were things in the elections before Trump?

SP: The highest, highest was Jimmy Carter, after Watergate, bear in mind, and a Southerner, he got 48% of the white vote. But in the past 40 years, it’s been a fairly narrow band from mid-thirties to low forties in terms of white support for the Democratic nominee. And it’s important to note, too, that while Hillary’s support was down around 37%, actually that’s close to what Obama got in his reelection bid. That’s history. But also, it’s very important to recognize that a meaningful number of people voted for Jill Stein and Gary Johnson. They assumed Hillary had it in the bag. They weren’t thrilled about her. So they cast these protest votes and we saw what happened with that.

JW: What I like best about your work is that you are not a pundit. You are a researcher. You’re not telling us just your opinions. You tell us conclusions based on your research findings, and your research is intended to shape political action, where to focus organizing, where to focus funding. You are reporting on a big study you and your colleagues have just completed. You called it Expanding the White Stripe. First of all, explain that title?

SP: It’s the white stripe of the rainbow, that the coalition that the progressives need is a rainbow coalition of people of all backgrounds and part of that is the white vote and how do we expand that? And so that really grew out of a collaboration that I did with the groups showing up for Racial Justice SURJ, which is explicitly focused on organizing progressive whites, and the Working Families Party. And what we did was we looked at what does the data show? There’s all this focus and attention and energy and emotion, frankly, around how do we get more white support, but there’s not a tremendous amount of data and evidence and analysis. And so we’re like, Let’s just look at the data. What does it show? What does it actually say in terms of what’s possible?

JW: Another key element of your research is that you don’t just focus on registered voters or likely voters, which is the focus of almost all polling, you’re especially interested in non-voters, infrequent voters, and the people political scientists call “low propensity voters.” We’ve been told by the pundits that, especially this year, a lot of the low propensity voters are alienated people who are potential Trump voters. But how many of them are potential Biden voters? What did your research find about that?

SP: Fundamental fact: if you look at the 2016 and 2020 elections and that electoral data and the Pew Research has done in these deep, deep dives around the elections and then the composition of the non-voting population in each of those elections, in both of those elections, the non-voters were actually more progressive than the actual voting population. And so some of this was flagged for me in 2020 really by Michelle Tremillo in Texas, the Texas Organizing Project, the effort there had said that they’re doing a better job of getting out their infrequent voters than we are. And so lost to the history is that Trump got 10 million more votes in 2020 than he got in 2016. So he brought out and inspired a lot of the non-voters and the conservative non-voters, but then left the non-voting population as even more progressive, likely progressive than the overall population. So if you take the percentage of whites who voted for Biden, which is around 42%, the non-voters are slightly more than that. And that means there’s 27 million whites who did not vote in 2020 who would likely have been Biden supporters.

JW: 27 million white potential voters did not vote for Biden and potentially could this year. So the question is how to reach those people. A lot of pundits suggest that white people do not like to hear talk about racial justice and minority rights. The way to reach them is to talk about their own bread and butter issues about wages, jobs, the cost of living, the cost of food and rent. What have you found about staying away from racial justice as a way to win the votes of those white non-voters?

SP: The largest level of success, two of the largest, most successful levels of success Democrats have had in the past 40 years in getting white voters is when we challenge the country to elect a Black man as the president. And that gets overlooked in terms of what had happened, that we summoned the nation to a higher level of being better and moving forward and making history and addressing with the problems from the past. And so that remains a pretty strong data point. And then if you look in addition on top of that, that there’s really a lot of suggestion that, particularly if you look at the non-voters being more progressive than the electorate overall, that there are people who want this to be a multiracial country. They don’t want to just subscribe to this notion that we should be a white nationalist country. There are white people who believe that. And appealing to their highest and best sentiments actually works more in that regard.

And so that’s I think a pretty fundamental piece to understand is that people respond to being summoned to be better and to move forward. And even if you look at this kitchen table thing, which I think it’s hilarious to think you’ll focus on economic issues. Joe Biden and the Democratic Congress in 2021 literally sent checks to just about every single American. You can’t get much more bread and butter than that.

JW: That’s a good point!

SP: And then his approval rating is still very low. So this notion about you generically do the bread and butter piece is not borne out by the actual data and evidence.

JW: So let me just underline over the last 25 years, the last six presidential elections, the Democrat who got the largest proportion of white voters was Obama in 2008. So the question is, which white voters should the Democrats try to win over? How can they be identified? And what’s the best way to reach them? Where should the funding go? Both candidates are raising tens of millions of dollars for their campaigns. Last weekend, Michael Bloomberg announced he was giving $20 million to Biden. Timothy Mellon is giving $50 million to Trump. Campaigns spend most of that kind of money on TV ads. So TV viewers in swing states are going to be drowning in TV ads for the later part of the summer and the whole fall. As a researcher, what can you tell us about the effectiveness of TV ads in persuading people to change their vote or in bringing out people who are non-voters?

SP: Well, it’s limited, that’s for sure. And so that’s one of the things that we really have to understand is that certainly you reach a point of diminishing marginal returns in terms of the amount of television ads – the impact. So just period as a vehicle. That’s one piece. More fundamentally is the difference around trying to change people’s minds, trying to persuade them to not support Trump and to switch to Biden. That is folly. And there’s very little evidentiary support for that – we are at a historic low point of swing voters within this country — that the polls have shown. So it’s more about mobilization. Stacey Abrams has this phrase of, “Persuasion’s like trying to get a Baptist to become a Catholic. Mobilization is trying to get a Baptist to go to church.” And so that’s what the challenge is, that you have far more, again, these 27 million, many of those are younger people and many of those are women, particularly in this moment of all these attacks on reproductive rights and Supreme Court rolling back Roe.

And so Mike Podhorzer, used to be a political director of AFL-CIO, he has this great metaphor around, instead of going after the white guy Trump voter in the diner in the Midwest, let’s pull the lens back, look at the person pouring the coffee for that diner who’s probably a woman, often younger, who’s much more likely to be progressive if they can overcome the obstacles that stand in the way of them voting. So that’s where money should go is to groups and staffing and door-to-door knockers to make sure those people are actually able to cast their ballots.

JW: One more thing here. Your real goal is not just to reelect Joe Biden. You have a longer term in mind.

SP: Very much. The essence of what I was trying to lay out in my first book is that there is a demographic revolution. Politics in this country used to be a battle between whites and you had conservative whites arguing against progressive whites over the whites in the middle because there weren’t enough people of color to make a difference. Since the ’65 Voting Rights Act and Immigration Reform Act, this country has gone from being 12% people of color to 41% people of color. So what that means then is now that the progressive white sector, that stripe of the rainbow allied with people of color is the majority of people. So the trend is very much in the direction of having the kind of multiracial, progressive majority that can bring about a public policy transformation that will make the country more equitable and just and progressive.

JW: I want to ask you another question, not about your research findings, but actually about your opinions. The New York Times ran an opinion piece by a former Biden staffer this week who argues that if Trump picks Marco Rubio as his running mate, Trump will probably win Pennsylvania, and that’s probably enough to make him president. But Pennsylvania has, he said, the largest Latino population of the three states of the blue wall, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Latinos, like other ethnic groups, are drawn to Latino candidates. And presumably Marco Rubio would also help in Nevada and Arizona, states that Biden carried last time narrowly. Do you think that Marco Rubio could win enough Latino votes in Pennsylvania as a vice presidential candidate to enable Trump to carry that state and then break the blue wall and win the White House?

SP: No. I mean, that’s clearly the take of somebody who doesn’t have deep knowledge or understanding of people of color in general, and of Latinos in particular, Biden gets 65% of Latino vote nationally in 2020. And so while The Times have this poll showing that the bottom is falling out. I think The Times is not very good at actually polling people of color. Biden’s not popular. That’s a given. And I think people are mistaking that lack of enthusiasm and lack of popularity with the fact that when they step into the vote in November, who they’re going to vote for, the actual elections, the majority of Latinos, around two-thirds of Latinos are going to vote Democratic. So could Rubio have some marginal impact among some people? Potentially, but in a state that’s as non-Latino as Pennsylvania, 8% of the population, less than of the eligible voters, it’s not like they’re all going to flip, first of all, just based upon that. And so even if there was some marginal shift, that’s not going to be transformative.

The other thing everyone is missing is how much population changes every single day. And so the electorate has millions and millions more people, more people of color, more young people than it did even in 2020. And so you can’t just look at 2020 and say, well, if you had a slight tweak here, then that’s going to make the difference because the trend actually is in the Democratic direction because of the numbers of people of color, the numbers of young people who are coming into the electorate, the majority of those whom are people of color.

JW: And we also need to remember that the Latino electorate is diverse itself and Mexican Americans in Arizona may not be as enthusiastic about a Cuban from Miami as some people in Florida are.

SP: 100%. That’s completely overlooked. And that’s where we won the election. It was Mexican Americans in Arizona who flipped Arizona, with the work of LUCHA and other progressive groups there to register half a million Mexican Americans over the past decade. So the bottom’s not falling out of that just because Marco Rubio might be on the ticket.

JW: I just have to remind our listeners of one thing about Marco Rubio. He and Trump exchanged these intense insults in the 2016 primary TV debates. Trump, remember, called him “Little Marco.” This is all on tape. And Rubio said that Trump had “small hands,” and, “You know what they say about men with small hands.” And this really got to Trump. Trump knows that the Democrats will run that clip a thousand times in the swing states. And according to Anthony Scaramucci, the former White House communications director, Trump will never pick Rubio as his running mate because of this “small hands” thing. It’s the kind of thing that really bothers Trump,

SP: Right. No, that’s what’s going to be fascinating is who is he actually going to choose? And there’s all this sense too they might choose, who is it, Burgum, who I hadn’t even heard of very much until recently, this billionaire white guy governor of North Dakota, because he resonates with him. And so it’s going to be a very visceral gut reaction for Trump in terms of who he chooses. So it’s entirely possible that any of these political calculations may not be the dominant factor in terms of who he chooses at all.

JW: One last thing. I know you’ve spent a lot of time in Arizona recently. Last time around Biden carried Arizona by 11,000 votes. What do you think Biden’s chances are there this year?

SP: I think they’re very good because of what I was saying that the electorate continues to trend in a more progressive direction. There’s hundreds of thousands of people under 18, the majority of whom are Latino, turning 18. So you have that. Very strong infrastructure in terms of the groups that were politicized in the anti-immigrant attacks back in 2010. Groups like LUCHA, One Arizona, Worker Power. So these are groups which are bringing more people of color into the electorate. And then you’re also going to likely have a ballot measure around protecting reproductive rights, which is going to motivate women to turn out in ways that they did in Ohio and in Kansas. So all of those trends very much are in Biden’s direction, the demographic trends, and then the infrastructure to make the most of it.

JW: Steve Phillips. That full research report that we’ve been talking about Expanding the White Stripe of Our Multicultural Coalition in 2024 is online at the website of the group Showing Up for Racial Justice, SURJ.org. And you can read his new piece about that report, it’s titled Democrats Must Change Their Approach Toward White People at thenation.com. Steve, thank you for all your work and thanks for talking with us today.

SP: Thanks for having me on. I enjoyed it.

[BREAK]

Jon Wiener: Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery and returned again and again to lead others to freedom. She became a powerful abolitionist speaker and then became the first woman in American history to lead a military raid, freeing 700 people. Now her story is being told in a wonderful new book, with the wonderful title Night Flyer. The author is Tiya Miles. She’s Michael Garvey Professor of History at Harvard. She’s written five other books on the history of American slavery that have won just about all the prizes that you can win, including the National Book Award for her bestseller All That She Carried. She writes for The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The New York Review of Books, and she’s a MacArthur “genius.” We reached her today at home in Cambridge, Mass. Tiya Miles, welcome to the program.

Tiya Miles: Thank you so much for having me, Jon.

JW: The opening of your book is in 1860, when Harriet Tubman is alone in the woods in Maryland, a slave state, as a winter storm approaches. She was supposed to meet a group of people escaping from slavery, but they didn’t appear. It’s a terrifying story, and it makes us wonder, how was she able to do it? Right away you let us know the answer. It’s the answer she gave when people asked her that question later.

TM: Yes. I began with this story because I wanted to try to reintroduce us to Harriet Tubman’s real and true and deep travails during her time as an activist and as a caregiver in the community of mutual aid. I felt that she had become so much of a legend in our minds that we had forgotten just what it meant to be not just a lone person, not just a lone Black person, but a lone Black woman in these moments when she was trying to help people escape from slavery. And so I went back to the primary materials and noticed this story that I’d come across before, but that hadn’t quite stood out in the same way, and just thought about what it would mean to be a young Harriet Tubman in the woods, in a snowstorm alone, with the people who were supposed to be meeting you actually not showing up, which could have all kinds of negative implications, and knowing that you yourself were being hunted.

JW: And what did she tell people when she talked about this at lectures later in her life?

TM: Well, the way I just painted this scene is as though Harriet Tubman would have to fend for herself fully and completely in this circumstance. But the way she told it was actually quite different because she talked about how she was not alone in that moment, that she was in fact never alone because the God of her belief was with her. And she added further that it was God who had saved her from getting frostbitten on that evening. So she felt that God was with her psychologically, emotionally, spiritually, but also apparently physically, that God was caring for her health in these times.

JW: So you show that she espouses what we call Black Liberation Theology. Could Harriet Tubman read? Did she read the Bible?

TM: She could not read the Bible, and this makes her one of many thousands of enslaved African-descended people, enslaved Black people who were not permitted to learn how to read and write by the rules and laws of the South. And even if they had had a legal right to learn, thney would not have had the time because of the ways in which their labor was being extracted and exploited. So Tubman could not learn to read and write. But that didn’t mean that she was lacking a rich interpretive intellectual and spiritual life. She had this to a great extent, as did many of her peers, because we know from Black theological research and writing, and especially a branch of this field known as Womanist theology, a Black feminist theology, that enslaved Black people shared their knowledge of God’s meaning, of God’s word, orally. They couldn’t all read the Bible, but they had certainly heard stories derived from the Bible or that they associated with the Bible, and they shared these. So they had a very rich, detailed understanding of God’s presence, God’s principles, God’s lessons, without having to read it for themselves.

JW: One of the key parts of your book is telling us about other Black women who were preachers and mystics, that there was a community, a whole world of Black female spiritual writers in Harriet Tubman’s life.

TM: Yes. I think I’m like many of us in that I always set up Harriet Tubman as sort of a singular person. Thinking back to grade school, thinking about the bulletin boards in my teachers’ classrooms with the picture of Harriet Tubman for Black History Month, I mean, she was often alone. Maybe Frederick Douglass would be there with her, but she was the person who really was highlighted as a singular figure who did all these incredible things. I carried that image with me as I went into this project. And it wasn’t until I returned to, again, some primary materials having to do with Black enslaved women and Black indentured women in the period that I realized Harriet Tubman was actually not so unusual in the ways in which she thought about her faith and the ways in which she thought about freedom, the ways in which she thought about those two areas in her life coming together.

There were many other Black women who had just as vibrant and, perhaps to some of our minds, unusual relationships with God as Harriet Tubman did. So Tubman felt that she had a very direct relationship with God. And for her, this is the Christian God of the Bible. It is very Old Testament-based because of the story of the Israelites being able to obtain their freedom from slavery. But it is also New Testament-inspired because Tubman believed in Jesus Christ being her Savior and being her companion. She believed this very deeply, and she operated in her world as if her God and her Savior were powerful animating forces in everything around her.

She had powerful visions, for example, that she thought were signs and communications or messages from the God that she believed in, and so did other Black women. We know this because many of them also told their stories to people who wrote them down. A few of them actually were able to write their own stories, and they talk about these very dramatic scenes, very dramatic incidents in which they see God operating in ways that would defy the laws of nature, let’s say. And so Tubman was among these women. And various turning points in her life actually map onto turning points in their lives in terms of the spiritual growth and development of a young woman.

JW: I want to talk about some of those biographical stories. She’s born in 1822 as Minty Ross to an enslaved family in Maryland. Her childhood was marked, you say, by absence, upheaval, and loss. In 1833, when she was 11, she and everybody else saw the night sky filled with a hundred thousand shooting stars and falling stars. It was an apocalyptic event for her. Please explain this.

TM: Harriet Tubman was a witness to an incredible astronomical event that took place in 1833, and this was the event known as the Leonid Meteor Shower. When individuals across the United States saw what looked to them like hundreds of thousands of stars that were falling to the ground, it was actually cast-off particles of a comet that they were seeing. But this experience in some ways connected people across vast geographical distances because they were all seeing the same thing, and people brought their conceptual frameworks to what it was that they were seeing. There were some individuals who felt that this was an incredible scientific inspiration, and there were other people who felt that this was an incredible religious inspiration.

Harriet Tubman and many other enslaved people who saw this phenomenon – and we know about that because they told their stories in oral interviews later on. Some of them wrote their own stories if they were able to read and write. These enslaved people saw the night that the stars fell as a time when God may have been indicating that He, because God was often gendered and masculine by these enslaved people at the time, that He had power over the Earth, that He had power over human relations, and that He would actually be seeking justice for people who had been wronged. So many individuals thought that this was a sign of judgment day finally coming, that God would come, and He would judge those who had sinned against others.

JW: And the second huge event in her youth was a head injury she suffered when she was 12 or 13. This story has gone down in history as a moment when her consciousness was changed and when a hero was made. You emphasize that she never fully recovered from that injury.

TM: Right. And this is something that I think probably every biographer of Harriet Tubman has written about, so it’s not my original interpretation that this violent incident was critical to Tubman’s development. And it moved her into really a different sensibility in terms of who she was in her own body and who she was in the world. But what happened is Tubman as an adolescent girl had been leased out to a farming family in her community because her owner tended to lease her and her siblings and her mother out to gain income from their labor. And she had been assigned, along with a woman who was probably a cook in this household, to go to the nearby general store and to get some supplies.

Tubman was in this general store, and she saw a person described as a young Black boy or a young, enslaved man running away from an overseer. But there are many different accounts of this moment, Jon, and it’s difficult when we look back at the past to understand or to ascertain exactly and precisely what happened. These accounts overlap to some extent, but they also vary to a certain extent. But the picture we get is that Tubman looked out. She saw this young Black enslaved boy or this young Black man, the term “Negro” is what is used in the original accounts, and she put herself in between this young Black person and the overseer who was trying to capture him, to recapture him. The young boy or young man seems to have been trying to escape.

The overseer picks up a very heavy metal weight in the general store and throws it at the young boy or the young man. And Harriet Tubman basically puts her body in between so that she’s the person who was hit by this weight. It strikes her in the head. She falls down and she’s so injured that the blood is just streaming down her face. She doesn’t have a clear sense of what’s going on. She manages to get back to the place where she has been leased out to labor. And even though she’s in terrible pain and she’s greatly injured, she’s put right back in the fields the next day. And she talks about how she was in such pain, she had a terrible headache, and she was just bleeding such that it was difficult to see while she was doing that enforced physical labor.

After this period, Harriet Tubman had a chronic illness. She had what scholars look back at now and describe as a temporal lobe epilepsy. She would have incredibly painful headaches that could strike her at any moment. She would have epileptic seizures in which she would lose consciousness. And the early descriptions of her tend to describe these moments as Tubman falling asleep and not being able to wake up or to be awakened by anyone until she just came out of whatever this episode was, she was having. For the rest of her life, she struggled with this chronic pain, with these unexpected symptoms, and with the ways in which they debilitated her. But she also may have developed an added intensity to her spiritual life as a result of injury and as a result of her epilepsy.

JW: The next key moment is 1849 when she was 16, and she escaped from slavery for good. You open that chapter of your book with a line from the spiritual, “I’ll fly away, oh glory, I’ll fly away.” Wow. In the moment she crosses into Pennsylvania in 1849, sets foot for the first time in free territory, she has a moment of transcendent joy. And then she says she felt like a stranger in a strange land. Let’s talk about that.

TM: Yes. Well, Harriet Tubman did run away in short bursts, as a younger person, she would run away to go visit her mother especially. And that’s actually where she was, Jon, when she saw the stars, visiting her mother when she wasn’t supposed to be. And actually, it’s quite a beautiful scene because one of her brothers would always be looking out to be sure that there wasn’t a patroller who could notice that Harriet Tubman wasn’t where she was supposed to be. And it was that brother who told her, “Come out, come out and see the stars.”

She was regularly leaving and regularly moving about in the way that she felt was right for the priorities she had set in her life, one of which was the care of family. But it wasn’t until she was in her late 20s that she actually was able to make a permanent escape from slavery. And that’s the moment that you’re talking about now. Throughout Night Flyer, I have interwoven lines from African American spirituals because the notion came to me as I was learning more about Tubman and learning more about this dimension of her life. It just seemed exactly the right thing to do, to headline each moment in her life with these spiritual expressions that were put to song, to musical note. Tubman herself was a singer, and song is an important expression of her belief and also an important way that she communicates with many other people during her years working on the Underground Railroad.

For this chapter, I chose that particular spiritual because Harriet Tubman, in one of her very vivid dreams, which became more vivid after that terrible incident in which she was injured, imagines herself as a bird. And she imagines herself as a bird flying across an incredibly varied and detailed terrain. And Maryland was a beautiful and diverse state, ecologically speaking. There are many different aspects of Maryland’s topography and the kinds of trees that grow there, the kinds of animals that live there. And Tubman had dreams about herself as a bird flying over this rich and varied landscape. But every time she would almost reach the line that she describes in her dreams, which is the line between slavery and freedom, she would fall, or she would plummet. Something would happen so that she could not quite make it over. So this dream of freedom for her was also at the same time a nightmare.

It was a dream about her desire to be free, but not being able to ever accomplish it, until she does. And that’s the moment that you were just describing for us. She does finally make it, as a human being who has this association of herself with birds, across the line. She makes it to Pennsylvania, she makes her way to Philadelphia, and she has accomplished this incredible feat, which most enslaved people were never able to do for many, many reasons, especially having to do with their location, where they were, whether they were in the upper South or the lower South, whether they were near a waterway or in an interior area. But Tubman did do it. She crossed the line, and her first thought seems to have been how beautiful the world around her looked in this new state of freedom. And almost simultaneously, her next thought seems to have been, and yet her family members were still behind that line of enslavement.

And in Tubman’s dreams, slavery is hell. She uses this language quite directly later on, after she escapes for good. Slavery is hell. And so she was on the bright side of this dividing line and her family was on the dark side of this dividing line, and she just could not live with that. She was terribly pained by the recognition. And she determined right then and there, on the ground, through a great deal of prayer and conversing with her God, that she was going to go back, and she was going to get them, and she was going to see all of her people free if God would only aid her.

JW: I want to go back to that winter storm in the woods that you open with. Of course, it’s a powerful metaphor: Harriet Tubman weathers the storm. But you’re interested not just in the metaphor, but in those woods, in the trees, in that wilderness, in Harriet Tubman’s understanding of what we call ecology. And you quote a wonderful line from one of the other Black female liberation theologians, Zilpha Elaw – “It seemed as if I heard my God rustling in the tops of the mulberry trees.” Let’s talk about the place of nature in this Black Liberation Theology that Harriet Tubman was part of.

TM: One of the things that I really enjoyed and appreciated about going back to these early Black women’s spiritual memoirs, which were also sometimes functioning as slave narratives, is that these women such as Zilpha Elaw were talking about the natural world around them. Their faith was connected to nature. Their sense of God and God’s presence was connected to nature. And this sense grew out of a Black religious tradition, which was connected to nature. Some of us may have heard words from a spiritual about going into the wilderness, and this is absolutely linked to a Black enslaved sense that the wilderness was the place where a person could find God, could meet God.

This was also connected to a reality in Black enslaved people’s lives, which was that they were almost constantly under surveillance. It was very difficult for them to find spaces of free expression. The woods could sometimes function as these spaces. The woods that were further out on a plantation, for example, or that existed between one farm and another farm. These are the places where Black people tended to go to join together, to pray, to dance, and to worship. So this has deep roots in Black religious life and Black enslaved people’s lives, the sense that spirituality is deeply linked into nature. And I got to, I guess, relearn that by going back to these memoirs because where I hadn’t seen it before, this time around I saw it everywhere.

JW: I want to ask about your wonderful title, Night Flyer. Where does that come from? We know that she had dreams of flying. You’ve told us about that.

TM: Yes. I am so glad you like the title because I love the title too, Jon. I just love the title. These were the first words that came to me when I tried to figure out how would I encapsulate this vision, this perspective of Tubman that I’m putting forward in the book. And I’ll share with you that this is the very first time, the first time ever, that I have written a title from start to finish that my press editor said, “Okay, yes, that’s it. That works. You don’t have to revise this title.”

“Night Flyer” is meant to help us think about Harriet Tubman, just as you said, as the bird that she imagined herself to be in her dreams. So there’s a dreamlike quality that I’m hoping to convey with this title, but it also directly points to Harriet Tubman’s physical actions in a material world. When she carried out her own escape, when she helped others to escape, she did it by night, and she flew, in a sense, through those woods. And so I’m hoping that these two words together will help us to hold in mind both the spiritual and imaginative, the dreamlike sense of Tubman, and the physical material ecological aspect of Tubman’s history.

JW: Tiya Miles — her new book is Night Flyer: Harriet Tubman and the Faith Dreams of a Free People. Tiya, thank you for all your work – and thanks for talking with us today.

TM: It’s been a pleasure. Thank you, Jon.

Subscribe to The Nation to Support all of our podcasts

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation