The Triumph and Tragedy of Betty Friedan

On this episode of The Time of Monsters, Moira Donegan on lessons from the life of a feminist titan.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique (1963) and one of the founders of the National Organization for Women (NOW), was a hero of feminism, but a complicated and difficult hero. Her book and activism were pivotal for igniting second-wave feminism in the 1960s. But as head of NOW, her leadership was irascible and nettlesome, marred especially by her homophobic hostility towards lesbian activism.

In a recent review for The New Yorker looking at books about NOW and Friedan, Moira Donegan lays bare the contradictions of Friedan’s legacy, her world-changing importance but also the way she sabotaged both herself and the movement she did so much to create. On this episode of The Time of Monsters, we talk about the lessons of Friedan’s life and how they remain urgent in current feminist struggles. Moira is a frequent guest of the podcast. She’s a columnist for The Guardian and also cohosts a podcast called In Bed With the Right.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

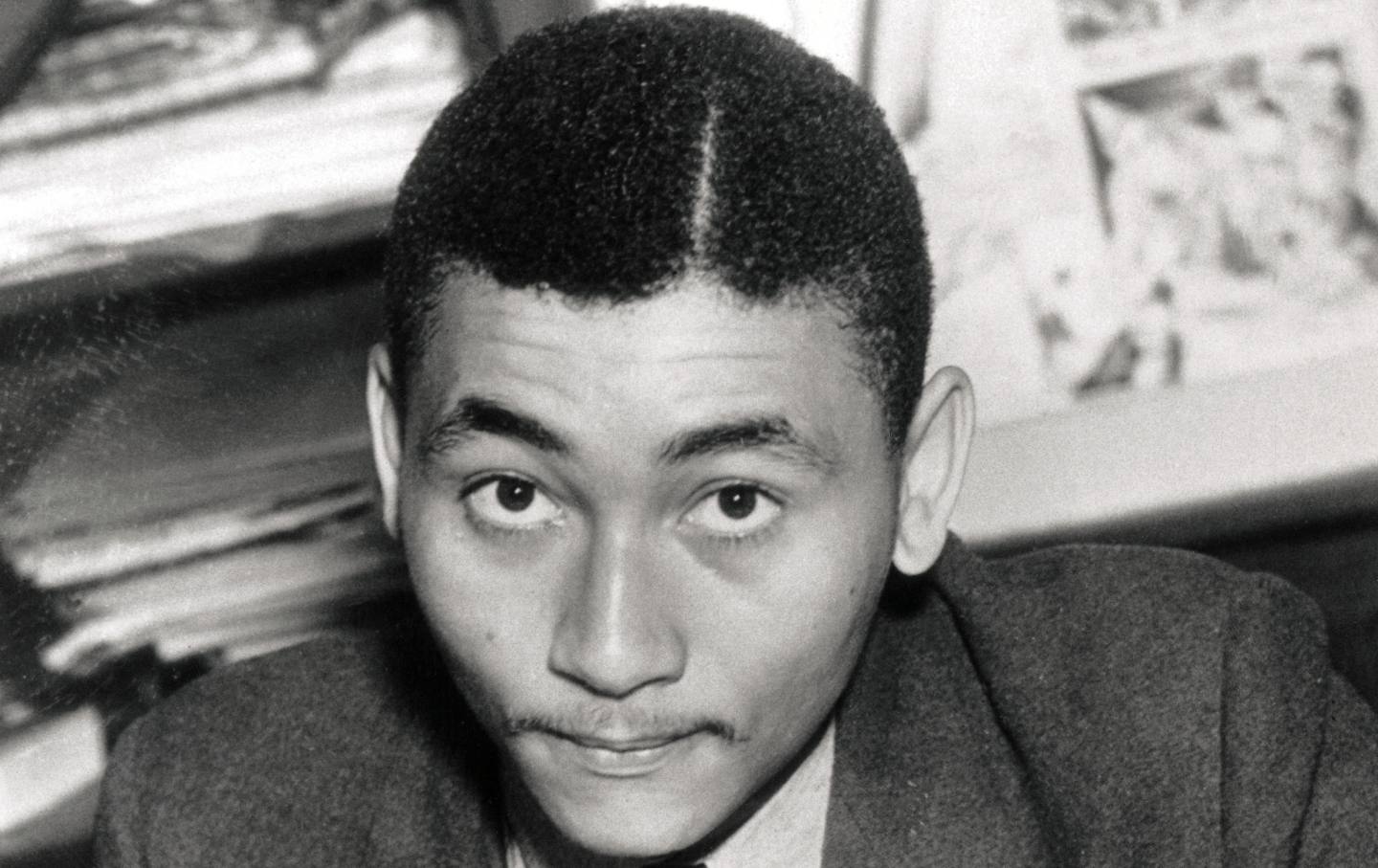

Betty Friedan.

(AP Images)Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique (1963) and one of the founders of the National Organization for Women (NOW), was a hero of feminism, but a complicated and difficult hero. Her book and activism were pivotal for igniting second-wave feminism in the 1960s. But as head of NOW, her leadership was irascible and nettlesome, marred especially by her homophobic hostility towards lesbian activism.

In a recent review for The New Yorker looking at books about NOW and Friedan, Moira Donegan lays bare the contradictions of Friedan’s legacy, her world-changing importance but also the way she sabotaged both herself and the movement she did so much to create. On this episode of The Time of Monsters, we talk about the lessons of Friedan’s life and how they remain urgent in current feminist struggles. Moira is a frequent guest of the podcast. She’s a columnist for The Guardian and also cohosts a podcast called In Bed With the Right.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

The Trump administration has released a new National Security Strategy that is a marked shift

not only from earlier administrations but also Trump’s first term in office. While the new policy

statement eschews the goal of global hegemony, it promotes culture war in Europe by

promising support of anti-immigration political parties, economic rivalry in Asia with China, and

a renewal of US military hegemony in the Western hemisphere. To survey this document and

Trump’s often contradictory foreign policy, I spoke to frequent guest of the show Stephen

Wertheim who is American Statecraft senior fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International

Peace.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Jeet Heer:

The old world is dying. The new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters. With those words that we welcome you every week on the Time of Monsters podcast, I’m Jeet here. The podcast is sponsored by The Nation magazine. It’s widely available on all podcasting platforms. This week we’re going to talk about someone who’s, I don’t think I would call a monster, but maybe a problematic fave. as the kids say, which is Betty Friedan, who’s a major figure in second wave feminism, has always been a kind of center of controversy, including from people who have shared her politics, but has a huge legacy and a legacy that I actually think is perhaps more relevant now than it’s ever been. talk about Betty Friedan. I’m very happy to have on frequent flyer on the In Time of Monsters podcast, frequent flyer program, Maura Donigan, who is a columnist at The Guardian, a fellow at Stanford University, and also has her own quite excellent podcast, which I would encourage people to check out, and I will put a link to it, called Embed with the Right. where she and Adrian Dobb talk about the intersection between right-wing politics and gender reaction. And among the delights of the podcast, they talk about people who are long-time vetenoirs or problematic not faves, but problematic villains like midgetector. who listeners to this podcast will be very familiar with, as a sort of underrated super villain of post-war American life. So let’s talk about Betty Friedan. And maybe the way to start it is just like, as I mentioned, she’s like, on the one hand, a very major figure, but has always been at the center of a storm of controversy. So maybe just like outlining you know, like what her achievements are, but then also what are some of the questions that people have had about her?

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, so Betty Friedan made a lot of pretty profound misjudgments. And some of those were motivated by what I think you can fairly call just plain personal bigotry. Right? And also, she dramatically changed gender relations in America. She dramatically changed federal policy. She was a… sort of founder in this way of the second wave feminist movement that without her it would never have happened and our lives would not look the way they did. I think they would have looked tremendously worse if it were not for Betty Friedan, right? So this is, you know, one of these figures of history who was personally small and politically quite outsized, right? She had

Jeet Heer:

Hmm.

Moira Donegan:

these principles and ambitions that her personal character didn’t really match up to. It was part of why I really loved spending a lot of time with her recently when I wrote a review for The New Yorker of these two new books that cover The Second Wave and Betty Friedan in particular.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, well, let’s maybe try to situate her a bit more like in sort of history. You know, like she’s born in 1921, you know, is initially like sort of politicized into the radical left as a communist party member. I think in your piece you mentioned she’s like too intellectual for the communist party.

Moira Donegan:

Yeah.

Jeet Heer:

Ha ha.

Moira Donegan:

So like, maybe let’s give a little bit of like background for anybody who’s just like, who the hell is Betty Friedan?

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

So she is the author of a book that came out in 1963, called

Jeet Heer:

and

Moira Donegan:

The Feminine Mystique, which was a account of what Betty saw as a really a moment of anti feminist backlash that had occurred in the 1940s and 50s. And that had left American women worse off. than they had been before that period, right? So Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique, you know, The Feminine Mystique is sort of thought of as like the housewives liberation book, right?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

She is critiquing a ideal of white middle-class American womanhood that keeps women out of the public sphere and devoted to sort of hearth and home and, uh, homemaking and child rearing, right?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

And Betty… who had a background in psychology, she had gone to graduate school for psychology, understood this role as very psychically claustrophobic

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

for the women who were placed into it. And she also saw it as a historical anomaly. I think now from our perch, we can sort of use the 1950s as a shorthand for this like pre-feminist. gender status quo, right? Like

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

what it was before we all awoke to feminism, but feminism long produced in the 1950s.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

And the 1940s and 50s gender relation status that sort of created that 1950s housewife Betty Cleaver, feminine mystique era was the product of a real political project to get women out of the workforce, white middle-class women back into the home. and having more babies that was deliberate. And Betty Friedan really traces that project and sort of incited with her book, which was a massive bestseller, the sort of awakening of women to a rediscovery of feminism that a lot of them had sort of thought of as passe and left behind.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, no, I… That book kind of made her, you know, like one of the early and rare feminist stars of the period. I mean, just thinking about it historically, like the only other comparable figure would be someone like de Beauvais with like the second sex, which was also like roughly around the same time.

Moira Donegan:

Yeah.

Jeet Heer:

But there was not a lot of precisely because of that sort of backlash and suppression of feminism, the older feminist stars were not really visible anymore. Even the ones that were alive, like Margaret Sangster, she had sort of narrowed her program to like sort of birth control.

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, and Alice Paul, like a lot of the suffragettes

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

generation were actually still alive. They were in their 70s and 80s at the time, but they were considered so oppressively passe. Like

Jeet Heer:

Hmm.

Moira Donegan:

actually the way that young people in Betty Friedan’s era understood first wave suffragette feminism is almost identical to the way we and our young people in our era understand second wave feminism. It’s like, those are old white ladies. they are out of touch,

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

they, you know, we got what they wanted, and now they’re just kind of continuing to complain. It’s a narcissistic and excessive enterprise, right? Like that’s just a sort of like the idea. But without

Jeet Heer:

I…

Moira Donegan:

feminism,

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

like without feminism in that era, when Frijan was writing, you know, you actually, it turned out you actually need a kind of continuous feminist. force because

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

cultural inertia will like, and you know, the forces of misogyny actively will impose a gender hierarchy, which like women, actual real world women, including ones who are not heavily politicized, will find like, entirely unsatisfactory. And so in that way, I think you’re right that her moment of, you know, confronting an anti-feminist backlash that had been like largely victorious and trying to revive a feminist movement has a lot of parallels to our moment right now.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, and I’ll mention with the suffragettes. As it happened, I’d recently been watching with my daughter’s Mary Poppins and I hadn’t seen the movie for a long time and I’d totally forgotten that the mother of the family in Mary Poppins is a suffragette and she’s exactly

Moira Donegan:

I know that.

Jeet Heer:

kind of portrayed as, you know, I mean the whole motion of the plot is that because she’s so caught up in this cause and neglecting her family that they need the intervention. of this divine force of traditional femininity in the form of Mary Poppins. So anyways, otherwise a fine movie. But I think

Moira Donegan:

The trad

Jeet Heer:

if you

Moira Donegan:

wife

Jeet Heer:

want…

Moira Donegan:

comes in to save the children, yeah.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, if you do watch it with your kids, perhaps have a little conversation.

Moira Donegan:

Hahaha

Jeet Heer:

In any case, so that is her moment. And then she leverages, which I think is also quite impressive. Because we’ve had people who have had really successful books that deal with a topical issue. and then remain authors. I think the other interesting thing about her is that she leverages that into like an actual political movement of creating the National Organization for Women now. So, and maybe to talk about that. I mean, I think that makes sense in light of her like larger political history that she had this sort of prior political formation. that led her to be interested not just in being a best-selling writer, but the leader of a mass political movement.

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, Betty Friedan did not start off exactly with the ambition of being like a literary celebrity. She started off on the political left. So like you mentioned, when she went to college, she’s from small town Illinois. She’s literally from Peoria.

Jeet Heer:

Hmm. Ha ha ha.

Moira Donegan:

She was born in Peoria, Illinois in 1921 and came East for college and went to Smith. And that’s where she sort of had this political awakening. in the sort of like the war time and immediately pre World War II era as a communist. And she really became quite committed to communism in a way that was not yet taboo on the American left before World War II. So, you know, she later went to graduate school in Berkeley and she tried to join the East Bay branch of the Communist Party and they’re like, no, you’re too intellectual. you’re not allowed to be here, which like, have you heard, have you been, have you met any communists? They’re all intellectuals. Um,

Jeet Heer:

Hehehe

Moira Donegan:

but they didn’t want her. And you know, meanwhile, the F we only know

Jeet Heer:

I’m almost

Moira Donegan:

this because

Jeet Heer:

wondering,

Moira Donegan:

there’s an

Jeet Heer:

when I read that part in your essay, if there wasn’t some sort of gender dynamic there as well. Like it’s not that she’s an intellectual because they had like, you know, like people

Moira Donegan:

Yeah,

Jeet Heer:

like Oppenheimer,

Moira Donegan:

they had a lot of

Jeet Heer:

right?

Moira Donegan:

male intellectuals, right?

Jeet Heer:

Yeah,

Moira Donegan:

Yeah.

Jeet Heer:

yeah, yeah.

Moira Donegan:

And we only know about this scene, of course, because there was an FBI informant in the corner,

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

like frantically scribbling notes. And this wound up in her FBI file. The FBI was monitoring Betty Friedan from the time she was about 20 years old.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

Her file contains essays she wrote in high school. So she was on their radar very, very young. And, you know, she did have a degree of paranoia, especially sort of at the height of her career, the sense that she was going to be labeled a radical and exiled.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

And part of that comes, like, frankly, because she had been so deeply involved with the communist left

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

in her extreme youth. She had dated a bunch of guys in Oppenheimer’s lab, actually.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

Like, they, like, And then, you know, in the 1950s, when she’s a married woman, she starts seeing all of her ex-boyfriends get hauled in front of Joseph McCarthy. And what happened to them served as her like a stark reminder of what happens when you stray outside of the mainstream. So she had this like, political realignment in response to the Red Scare, in response to like these personal experiences that made her much more wary of the dangers of being seen as extreme.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, no, that’s right. The Macartheism is very formative. And I think that actually explains, although it doesn’t excuse, some of the homophobia. That like, you know, as I think historians have demonstrated, the period of Macartheism was also the period of the Lavender Scare. And the two are combined, that the sort of, you know, accusations of homosexuality were used to weed people out of the federal bureaucracy and sort of covert communism and covert homosexuality were seen as overlapping and intertwined dangers. And so for someone like Smith who had been part of the radical left, had seen it destroyed by the instruments of the state, and had seen how homophobia had been deployed as part of that counter-revolution and that social purge, I mean these are all like very formative. experiences telling her, you know, like where the dangers are.

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, I think that’s accurate. But I also think, you know, we’re getting, well, we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves and I can go back to the biography because you asked me about the formation of now and the national organization for women was a group that Friedan founded really in cooperation with a few other women, but especially Pauli Murray, the legal scholar in 1966 and the thing about Betty Friedan and her call for a feminist revival is that like she popularized the idea, but she didn’t like invent it, right? So in policy circles in and around Washington, there were a lot of women working for, particularly the Democratic Party and also particularly labor unions who had seen failures of the civil rights and labor movements to sort of grapple in ways that they felt were appropriate and serious enough with the issue of women’s equality. Uh, there was frustration with women’s backsliding, uh, in terms of their social status, income, workforce participation, uh, life options. You know, this had been a retreat from the public sphere that had happened in the 1940s and 50s. And these women were frustrated with that, uh, the same way that pre-DAN was. And then what really fucking pissed them off was the lack of enforcement of Title VII of the 1960 for Civil Rights Act. So

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

in 1964, the Civil Rights Act passed, Title VII is a provision within that Civil Rights Act that prohibits discrimination and employment. And in Title VII, there’s a prohibition, federal prohibition on sex discrimination and employment. And to enforce this, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is established. It’s a whole new federal agency meant to enforce non-discrimination law. uh, by employers and the EEOC commissioners consider the sex discrimination ban in the law as a joke. They start referring to it as the bunny law because they’re like, if we enforce this, we would have to make men be playboy bunnies at the Playboy Club. You know, it was, they were like literally laughing about it, right? Um,

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

but meanwhile, they’re getting tons and tons and tons of sex discrimination complaints at the EEOC.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

There’s. You know, the New York Times is running sex segregated help wanted ads. Like these are the good jobs that men can get. And here on this other page are the bad jobs that women have to settle for. Um, flight attendants are being fired at the age of 32 or if they’re over 125 pounds. Um, There’s not a word yet for what we call sexual harassment, but it’s a endemic feature of women’s experience and paid work. And this stuff is not really in the popular consciousness the way that it is now, but that

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

does not mean that women are okay with it. They’re actually profoundly pissed off and looking to the state for redress in accordance with the law, and the EEOC is refusing to enforce it.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, no, I mean, in terms of, I’m really glad you mentioned Polly Murray because, you know, like she represents, you know, the sort of legal side of this. And you know, like she’s an African American woman. For our later discussion, you know, when we returned to the issue of sort of homophobia, you know, very interesting because, you know, like it’s clear from her biography, she had said that she was a man trapped in a woman’s body. But

Moira Donegan:

And

Jeet Heer:

she was also,

Moira Donegan:

relationships with women, you

Jeet Heer:

yes.

Moira Donegan:

know, sexual relationships work seemingly exclusively with women, yeah.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, and was a pioneer of the idea of a legal strategy on the issue of civil rights, and then later on the issue of women’s rights. That’s to say that in the sort of early 20th century, it was like unclear, what was the best path forward for overcoming Jim Crow and segregation. And she was like one of the real pioneers that said, like the key instrument of the state and the power of the state, is in the laws, that if we can get, you know, Plutzy versus Ferguson overturned, if we can, like, you know, like, get civil rights laws overturned, that will be an instrument of power. And, you know, like, more crucially, like, to distinguish that between, like, later forms of legal liberalism, that’s in combination with social mobilization, that you both get the laws in place, and then you get people who understand these laws or are taught about these laws and what their rights actually are and can mobilize to push for them in the real world. So I think that’s a crucial component. And I would say that Betty Friedan herself then becomes very important. Because if you have people that are starting to put in the proper legal language and it’s not enforced, then you need like, you know, a popularizer, someone who can like, you know, name the problem. Like, I think that that’s a crucial part of a feminine mystique. Like, people had this, as you say, discontent. Women had this discontent, but they didn’t have a name for it. And she was the one who named it. And that’s like just a

Moira Donegan:

She

Jeet Heer:

huge

Moira Donegan:

called

Jeet Heer:

thing.

Moira Donegan:

it the problem that has no name.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

But you’re describing a social change strategy I’ve heard called suits and boots, which

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

is this idea that you need both people who can manipulate existing institutions, seek reform or enforcement of existing rules, who can be playing on the terms of the elite. Uh, and that’s something that, you know, people like Pauli Murray are great at. Those are lawyers. Uh, those are lobbyists. Um, act up was in this model as well. Um, they had sort of an insider group, uh, the NAACP, which now was eventually modeled on, had this model, but then you don’t just need them. Right. You also need a massive, uh, group of. people who can be taken to the streets and who can impose pressure in these, like sort of less institutionally refined ways. So you need both the suits in the courtroom and the boots

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

on the street suits, suits and boots. I think it’s cute. But

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, no,

Moira Donegan:

you know,

Jeet Heer:

no.

Moira Donegan:

this

Jeet Heer:

It describes the actual, you know, the way the movement came together in the 1960s. And I would add, like in our discussion of freedom, like there tends to be a tension between the suits and the boots, right? Like the

Moira Donegan:

Yes,

Jeet Heer:

people

Moira Donegan:

yeah.

Jeet Heer:

who are, you know, like there’s an inherent going to be conflicts over locals.

Moira Donegan:

They don’t trust each other.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah,

Moira Donegan:

Yeah,

Jeet Heer:

they don’t trust

Moira Donegan:

this

Jeet Heer:

each

Moira Donegan:

is…

Jeet Heer:

other. Yeah, yeah. Because they have like a different orientation and different… like focus in like what they should be doing. Even though everyone can see them working together like on a macro level, but that’s not how it’s felt existentially. Existentially

Moira Donegan:

Yeah,

Jeet Heer:

it’s felt like.

Moira Donegan:

retaining those allegiances is the impossible task that virtually everybody, every group fails. I actually think for a really good account of this, readers should consider picking up Sarah Schulman’s history of Act Up called

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

Let the Records Show. It’s an absolute doorstop of a book. It’s like 800 pages, but it’s a really good illustration of how the alliance between the people on those two tracks eventually like It was very, very effective for some years and then eventually broke down, which is something that we can also see happen towards now, sort of later in its history. But what happens is that there is this discontent among the elites and these credentialed experts in Washington. There’s not a ton of women working in politics. The parties at the time had what were called ladies’ auxiliaries, which is where, like, if you were a woman working in politics, you had to sort of go and sit at the kids’ table. But there were enough of them, this woman named Catherine East in particular, who was like a democratic party operative, was very well connected. And they sort of came to Friedan and they’re like, be our big public face. Make our, like transform our backroom pressure campaign into a legitimate social movement that can pressure the federal government from the outside. And that’s where we find Buddy Friedan. in her hotel room in Washington, DC in 1966

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

with a room full of very drunk women trying to, you know, from various states who are involved in sort of advocacy for women’s rights, trying to get them all to sign on to this and she winds and it winds turns into a screaming fight.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm. Heh,

Moira Donegan:

It’s

Jeet Heer:

heh,

Moira Donegan:

an amazing scene

Jeet Heer:

heh.

Moira Donegan:

and

Jeet Heer:

Yeah,

Moira Donegan:

I

Jeet Heer:

I don’t

Moira Donegan:

had

Jeet Heer:

know.

Moira Donegan:

read

Jeet Heer:

I don’t

Moira Donegan:

it.

Jeet Heer:

know.

Moira Donegan:

I had read about it before, you know, Polly Murray, they call this meeting of these women, everybody’s in town for this big conference. So they call a meeting and it’s after this big reception at the State Department that had

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

apparently been very boozy. So everybody kind of staggers in at like midnight to Betty Friedan’s Hotel Suite at the Washington Hilton and they’re like, oh, it’s a party. Like Betty’s having us here for a party. And

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

then they’re still drinking, they’re drinking from the mini bar and Pauli Murray gets up clutching her little yellow legal pad and begins to talk in her very like, um, a faceless, proper Pauli Murray way about this new organization she wants to launch, like called

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

the, that she’s calling the NAACP for women, but oh, why don’t we call it now?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

And these women who are kind of just there to have a good time.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

are like, ah, do we need to, do we have

Jeet Heer:

Hahaha.

Moira Donegan:

to, do we really wanna, can’t we just work with, you know, within the existing structures? And Betty Friedan, in very typical Betty Friedan fashion, screams at everybody, tries to throw them out, and then locks herself in the bathroom.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, no, it’s quite the scene. I’ll just say like tangentially, like, you know, we can kind of maybe historicize the drinking there. You know, this is the sort of Mad Men era, you know, like people are at that period, you know, drink much more, especially in things like sort of, you know, conventions and political events. And then also like, you know, although men like, you know, Teddy Kennedy were obviously huge alcoholics, there’s a little bit of a gender dimension as well, in the sense that you know, like in this oppressive, patriarchal world, you know, like alcohol was one of the means of self-medication. It was like, you know, mother’s little helper, as it was known. So, so it kind of, you know, the drinking, you know, it has like, we could, we could sort of understand it historically, but it is like quite the scene. And, but I mean, I think it makes it all the more impressive that Murray and Ferdinand were able to like, you know, get everyone within

Moira Donegan:

Yeah.

Jeet Heer:

that chaos to actually create this organization. And then I think what the suits and boots strategy really kicks in once you have now as the sort of megaphone or the voice of discontent that people can rally around. I think in your piece it comes out very strongly. The interesting thing is how many women who are not otherwise politicized or politicized in the way of a left social movement get attracted once they see, oh, there’s this organization, it’s concerned about what’s happening to women, it’s concerned, especially rape right now. Abortion is a huge rallying cry because

Moira Donegan:

Yeah.

Jeet Heer:

that’s something that then as now, a lot of women like experience in their lives. And that’s something that, you know, cuts across all demographics and political lines.

Moira Donegan:

And even if you don’t experience it, you have to think about it, right? Uh, cause it always could be you. Yeah. The.

Jeet Heer:

Or you know someone or

Moira Donegan:

Yeah.

Jeet Heer:

you have an aunt

Moira Donegan:

Um.

Jeet Heer:

or a mom that had an abortion. It’s just like woven into the fabric of everyone’s life.

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, that was 1966 is a pretty raw era.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

And it is an era of part of the anti feminist backlash of the 1940s and 50s was renewed and often quite draconian enforcement of abortion bans that had been more laxly enforced in prior eras and then an attendant surge in women’s mortality rates.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

So Betty Friedan. really shapes now in her own image. She’s the first president. She served for four years until 1970. And she sets out a series of goals. The first is like actual Title VII enforcement and employment non-discrimination. She wants abortion rights. She wants the ERA and she wants a national child care program. Title VII enforcement has been weakened in the ensuing decades, but they got it. Like the EEOC considers sex discrimination to be banned in federal law now. And they did not when Betty Friedan started, and they probably wouldn’t have if Betty Friedan had been on their ass. They changed, worked very hard to change public opinion on abortion, which did facilitate the Roe v. Wade decision. We have lost that since. But we gained it in no small part because of now’s work, and also because of Betty Friedan’s work, because partly, Another thing she did during this era was found in ARAL, which is, you know, a whole other large women’s rights organization, National Association for the Appeal of Abortion Laws, which I believe has since changed its acronym. But that was an effort Betty Friedan made to sort of recruit an alliance of healthcare professionals and feminists who had sort of been. separate and historically occasionally opposed on the question of abortion rights, but were like coming around to shared support of abortion rights in the 1960s and again really solidified that alliance with NARAL. Another goal she had was National Child Care Program, which they very nearly got it past the Senate, it passed the House. President Nixon was about an inch from signing it and then Pat Buchanan, his arch conservative speech writer,

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

convinced him not to. And everybody in the country, by the end of Friedan’s term as president of now, considered the ERA a pretty much done deal. They’re

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

like, this is so banal. Of course we’re going to pass the ERA. And then an ally of Buchanan’s, Hila Schlafly, with substantial financial backing from groups like the Mormon church, organized to, you know, rally the far right and defeat the ERA. So,

Jeet Heer:

Hehe.

Moira Donegan:

you know, she, Friedan’s legacy and now’s legacy was one that really changed our world. And it is one that has been chipped away at very slowly. and deliberately, and now we are much more vulnerable to losing the gains that her work enabled us to achieve.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm. Yeah, no, and that’s one reason why I was thinking after reading your article, like how relevant her life is for now, because it seems like a lot of the same issues, you know, that politicized her and mobilized her and mobilize now in the 1960s are, like, again, pertinent. And a lot of the same strategic questions are very pertinent again. Now, At the start, I had sort of said, problematic fave, because obviously, the case you’ve laid out is very important, I think, is huge. This is someone who was responsible for and helped incite a movement that was responsible for these major transformative changes in American society. But she’s always been someone like. that people have had mixed feelings about it. So do you want to outline what some of the reasons for that are?

Moira Donegan:

Well, she was absolutely impossible.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

You know, I think there were like two times just in my piece where she gets so upset that she throws a tantrum and locks herself in the bathroom.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah,

Moira Donegan:

And I was

Jeet Heer:

yeah,

Moira Donegan:

on the phone

Jeet Heer:

yeah.

Moira Donegan:

with

Jeet Heer:

I was

Moira Donegan:

my…

Jeet Heer:

thinking that was a common strategy it seems like.

Moira Donegan:

At least I only found two, but I was

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

on the phone with the fact checker and he’s like, how often did she lock herself in the bathroom?

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, I don’t.

Moira Donegan:

And I was like, I only know of these two, but like, there’s another scene. And Rachel Steyer’s book is one of the ones that I review in which she doesn’t get her way and she sort of like slams the phone and then sort of like stomps her feet like a child, you know, she’s um She’s irascible Uh, and she can make these like great displays of woundedness, right?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

Um, that’s like kind of I think like an ordinary human failure, right?

Jeet Heer:

Sure, yeah,

Moira Donegan:

Um, I

Jeet Heer:

yeah.

Moira Donegan:

see I see in free Dan somebody with like,

Jeet Heer:

And

Moira Donegan:

you know,

Jeet Heer:

I

Moira Donegan:

maybe.

Jeet Heer:

should add, I mean, like if you’re thinking about it, like, you know, like, you know, these sort of like psychological quirks and problems are like, you know, like not unknown in like, you know, male leaders. Like I would not say Lyndon Johnson or Richard Nixon, you know, her contemporaries are like, you know, models of psychological health. So

Moira Donegan:

Right,

Jeet Heer:

and

Moira Donegan:

but like

Jeet Heer:

yeah.

Moira Donegan:

women are held to a higher behavioral

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, yeah,

Moira Donegan:

standard,

Jeet Heer:

that’s

Moira Donegan:

right?

Jeet Heer:

right.

Moira Donegan:

And like we see her personality flaws as out as like eclipsing her accomplishments

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

instead of the other way around.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

And we just don’t assess men that way.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

But I think the thing that really has left the stain on Friedan’s legacy was her homophobia and in

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

particular her homophobia towards Lesbians, which was like sort of the bulk of her homophobic attention was directed at women. Although the feminine mystique does have some nice, like, shivs at gay men. She’s like housewives become overly attentive and obsessed with their sons, which makes those sons gay, which is why we need to get women into the workforce. And I’m like, is that really why? Like,

Jeet Heer:

Well, I…

Moira Donegan:

I don’t, I think it’s, you know, but anyway, but like she really mostly she was. focusing on lesbians who were increasingly visible and increasingly out within the women’s liberation movement, the second wave feminist movement of the late 1960s and early 70s. And there’s a few reasons for this. There, you know,

Jeet Heer:

What we had

Moira Donegan:

there

Jeet Heer:

talked

Moira Donegan:

was

Jeet Heer:

about, just to circle back, we had mentioned earlier the sort of lavender scare of the late 40s and early 50s. But yeah, there are other reasons as well.

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, you know, there’s a nascent gay rights movement in the post Stonewall era. There is sort of an intellectually independent lineage of radical feminist thought that comes to embrace lesbianism as one legitimate expression of feminist identity. There is an increasing, you know, like Betty Friedan. comes from the far left, but I would position her very solidly as a liberal feminist, right?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

There is sort of independently emerging from the new left, as opposed to Friedan’s old left, from the new left, like anti-war civil rights, anti-draft movements. There is a new kind of radical feminism emerging

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

among people who are, you know, like 10, 15 years younger than Friedan, and they are much more interested in sexual politics.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

they’re much more interested in like how heterosexuality is constructed, how the family is constructed, how marriage and motherhood and dating are all sort of arranged around any presumption of women’s like self-sacrifice and submission, right? And Friedan is kind of allergic to that shit. She’s like, why would I give a crap about your personal life?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

And she sees the rise of a lesbian rights claim and the sort of like mass coming out of lesbians that was happening in this era as symptomatic of this like intellectual failure. But I actually think that you can explain this in part through Friedan’s own biography. Because Friedan was a woman who had like horrifically bad. luck with heterosexuality.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

I don’t think this like explains all of her views or like is, you know, a particularly useful way to assess feminists in general, but I think with Breedan it’s really interesting. You know, she had this background in psychology,

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

which was like a field she left in part because she couldn’t stomach the misogyny in the

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

field’s theoretical foundations. Like there’s a scene

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

of You know, she’s on a date with this psychology graduate student and he’s like trying to like nay her by telling her about like the theory of penis envy.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

She gets sexually assaulted by one of her graduate school professors. She

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

gets sexually assaulted by a couple of other dates. But she just can’t get like in her like very young life, she just can’t get boys to like her.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

Like men just don’t, they’re just not really interested in Betty. Um, she’s like very serious. She’s very like intellectually ambitious. She’s not like the prettiest girl. And then she winds up marrying this kind of piece of shit guy, Carl

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

Friedan, um, who like almost immediately starts like a cheating on and B beating her, um, she has a horrific marriage.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

And like Betty. is very disappointed in heterosexuality and she kind of, but she never gives up on it, right? She’s

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

always trying to make it work. And one of her rationales for feminism is like, no, we need feminism to redeem heterosexuality. We need feminism for love to work so that, you know, we can have this great flowering of affinity between equals and not be sort of kept from each other. by this hierarchy and inequality. And you know, sort of the, the accusation leveled against feminists or at least the one that’s been leveled against me, right? Is that like, you’re a lesbian because you failed at heterosexuality, right?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

And Friedan’s personal sense of having failed at heterosexuality made her a virulent anti-lesbian homophobe and

Jeet Heer:

Yeah

Moira Donegan:

like made her really double down on. of trying to succeed at and redeem this project of marriage and heterosexual partnership.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, no, that’s so interesting. I mean, because, you know, I mean, she was adverse to sort of politicizing the personal realm. But in some ways, she herself had already done that. Like she had, you know, made the heterosexual family the sort of normative bulwark that we have to make work. That is, I mean, by your account, that seems like the basis of the sort of project. And I mean, a couple of things you said, I want to sort of tease out. I mean, as is mentioned. earlier, the sort of formation, you know, of like, you know, McCarthyism and the lavender scare thing. And then but you mentioned that she was, you know, understood very early on. And this was going really against the grain of the 40s and 50s, the misogynist basis of like, you know, a lot of Freudian and other, you know, psychological models. And but she seems to have bought into. the homophobic basis of those theories, right? Because her idea is like, you know, the gay men are created by, you know, overproductive mothers, you know, is pretty standard. And so it is interesting the degree to which, you know, she is both buying into, you know, this very heteronormative model of the family, even as she… is aware as much as anyone is, you know, of like all its problems.

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, yeah, she, she really thinks that the way that you fix marriage and the family and like sort of create happiness within the home, which is like a unit she doesn’t really question, right?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

She assumes that there’s going to be a family home and that there needs to be harmony within it. She thinks that the way you get there is by creating as much formal and like practicable equality outside the home as possible. And like, there’s a degree to which like that is a decent argument. Like if you want to make it harder for men to like beat and rape, you know, the women in their private orbit, uh, one way to do it is to make sure those women have enforceable legal rights

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

that are taken seriously. One way to do it is make sure that those women have money so that they can like leave or sue his ass, um, you know, and these are one, another way to do it is to, you know, make sure that. uh, the law and the culture outside the home are enforcing women’s dignity so that it doesn’t seem so rational and acceptable to like beat and rape women in private. Um, so, you know, she’s not crazy, but she did kind of, she’s not crazy strategically, right? But I think her political understanding of these, you know, quote unquote private sphere aspects of women’s oppression as somehow lesser, uh, I think it blinkered and blinded her. And, you know, she was like not like passively homophobic in the way that I think we would like maybe like forgive a lot of people of that generation for being or at least expect them to be right. She was quite actively homophobic. She referred to lesbians as the quote unquote lavender menace. She threatened to out now as executive director who at the time was married to a man and sort quite, it sounds like quite seriously and painfully struggling with her lesbian identity,

Jeet Heer:

Hmm.

Moira Donegan:

you know, it was like she was cruel. She got women fired for being gay, like crazy shit.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, yeah.

Moira Donegan:

And it was really, and like to her credit, she changed her mind on this eventually, but not before she had really thoroughly lost the fight within the feminist movement, because this isn’t You know, when I went into this writing this piece and reading more about for Dan, I thought of now as institutionally homophobic, right?

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

I assumed that this was something that her fellow leaders in the group endorsed, that it was something that the group’s membership sort of like implicitly or explicitly endorsed. And that’s in fact, not the case at all. This was

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

Betty’s problem. And the rank and file made it clear that they were not on her side and that they, you know, wanted to embrace lesbian rights or at least not exclude lesbians as fiercely as Friagin wanted to. So like the respectability politics that Friagin was very fiercely advocating for by even the early 70s, they were like losing an appeal among the liberal feminists, sort of shock troops that she was relying on to make now a relevant national organization.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, and not just liberal feminists. I mean, like, it’s sort of interesting

Moira Donegan:

Thank you.

Jeet Heer:

that even the sort, you know, that she wanted to get, you know, respectable Republican women on board and even those at that time, and then just might have changed later. But at that time, we’re not like into homophobia at the degree that she was, right? Like, so,

Moira Donegan:

Yeah,

Jeet Heer:

yeah.

Moira Donegan:

Catherine Turk’s book, The Women of Now, which is one of the two books that I reviewed, features this woman, Patricia Hill Burnett, who was a Detroit housewife, and she was like, I’m a philanthropist, I like to paint watercolors, and she was drawn to now, in large part because of their support for abortion rights.

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

And she was um, you know, sort of elite conservative woman. She had been Miss Michigan in her youth. She was like very pretty. Um, and she was like, I have no appetite for this anti-lesbian shit. She

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

was like, I don’t, she’s like, this seems pointless. Uh, men hate all feminists anyway. Like there’s no

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

point in capitulating to respectability politics because we’re just weakening ourselves. Um,

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

so this was not. Like, you know, Betty Friedan very much saw herself as sort of protecting now from the judgment

Jeet Heer:

Hmm.

Moira Donegan:

of mainstream women, from the rejection of mainstream women with her homophobia, right? She thought it as like strategically smart. But these like mainstream women who she’s imagining are not really like lining up enthusiastically behind a homophobic message. They’re kind of like shrugging at it.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, well, and I think that actually has also sort of resonance for now because I mean one does see, you know, like a kind of on the left like a kind of argument for you know, semi Transphobic views on the idea. Well, you know like Transpolitics alienates people and it’s you know, we have to like, you know win a Large coalition and The thing is, I mean, I’ve talked about this before on the podcast, there’s not a lot of electoral evidence of this. I think actual transphobia doesn’t really do that well politically, especially in actual contested elections. But beyond that, the people making that, I mean, it seems like a bad faith argument. You’re conjuring up a popular transphobia to justify your own policy preferences. I feel like

Moira Donegan:

Right.

Jeet Heer:

that’s what Friedan was doing a bit like, you know, conjuring up. We have to appeal to these hypothetical, like, you know, women who would support feminism, but would be alienated by lesbianism. But that’s actually like, because, you know, she herself was homophobic, right?

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, like…

Jeet Heer:

Like, I don’t want to be too, like, crudely cynical, but that does seem to be the move, right? Like you justify

Moira Donegan:

Well, yeah,

Jeet Heer:

your.

Moira Donegan:

it’s like, it’s not me. It’s, it’s like bigotry by proxy. It’s like

Jeet Heer:

Yeah,

Moira Donegan:

you

Jeet Heer:

yeah,

Moira Donegan:

invent somebody else who’s a bigot to justify

Jeet Heer:

yeah.

Moira Donegan:

your own bigotry. But like also, you know, Friedan’s focus on respectability politics really does remind me a lot of like the contemporary reactionary centrist

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

position, uh, and sort of like the reflexive, you know, democratic political consultant idea that you’re always pitching to the Trump voter in a diner in Iowa. in Ohio, right?

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, yeah.

Moira Donegan:

And like assuming that person’s like A is a majority, B like can be persuaded to like support you in the first place. And like C is intensely motivated by the things that you’re assuming they’re motivated by is a persistent fantasy even without evidence, right? Like the evidence that I think we’re seeing. piled upon us both in Free Dance era and ours. Is it like abortion rights? Is it like incredibly popular? And that you can garner a ton of support by backing them

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

and by making them a central issue and that, you know, homophobia, transphobia, queerphobia, it’s certainly very alienating or very animating to some people but only a small minority who are never really going to be on your side anyway. Like the

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

trans thing, kids in sports, you know, 90% of voters are going to be like, what are you talking about? What’s wrong with you? Who could possibly give a shit? Like they’re not motivated by this. Like even,

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

even the people who might be. you know, persuadable to a transphobic argument, don’t feel as strongly about it as the people informing us so breathlessly that this is their number one issue, you know.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, no, I think that’s absolutely right. And I think it’s the degree to which respectability politics depends upon creating a fantasy of a popular base that is winnable. And rather than trying to actually build the coalition that you already have and work with the people that are already on your side.

Moira Donegan:

or taking any responsibility for persuasion. You know, the thing about

Jeet Heer:

E-S-S.

Moira Donegan:

like politics, law, these big organizations like now is that they don’t have to just conform or like shape themselves around public opinion. They have some influence, at least over changing public opinion,

Jeet Heer:

Yeah,

Moira Donegan:

right?

Jeet Heer:

yeah.

Moira Donegan:

And that was something that Friedan actually was quite willing to do on some issues, like the ERA and abortion rights, neither of

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

those was like especially popular. when she took them on, but she found that they were sort of paramount importance to her that she was willing to do something that risked alienating her allies, right? Like that risked undermining relationships that were important to her. Like the unions were a huge part of now’s early coalition. Like one of the things you learn when you study the second wave is that like a lot of second wave feminism. was only possible because of the presence of labor unions and

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

women’s heavy enrollment in labor unions in a way that makes the idea of reviving that kind of national feminist project seem really impossible today. But they didn’t support the ERA. And when at NOW’s second annual convention, Betty Friedan pushes through endorsement of the ERA, all the union women walk out because their union doesn’t allow them to be a part of a… organization that’s lobbying for the ERA, you know, and she was willing to do that because she thought it was important enough. She wasn’t willing to do it with the lesbians, which I think would have cost her less. Ultimately, opposing lesbian rights cost her much more than I think opposing them would have ever gotten her.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, yeah, no, and then that sort of point to her Her personal political tragedy, but then I think I think also resonates with A lot of issues like now like there are people who you know, like Are picking heels to die on and I think are very strange heels And uh, uh That’s also um, I mean, I think it’s always useful in politics to step back and think like why am I? like, you know, making this the, you know, the litmus test and the thing that I will like, you know, destroy everything for. And yeah, it’s a, but I mean, like, you know, having stepped back, I mean, you know, in your piece, and I’m very glad that you bring this note and sort of end on this note with, you know, like, like for all the sort of, you know, criticism that we have of her, you know, and then these are like major important criticisms. You know, there’s still the sense of achievement and I think I think you really bring out like all the contradictions with the story of the general strike in like 1970 and Did you want to just like maybe that’s a nice note to end on because it both

Moira Donegan:

Yeah.

Jeet Heer:

brings out her difficulty As a person but then also how that was actually good in a movement leader

Moira Donegan:

Yeah, so, Free Dan is, she leaves the presidency of now in 1970. And she’s at this meeting in March of 1970, sort of handing over the reins to her successor, Eileen Hernandez, who’s a really interesting figure in her own white right, a black woman, women’s rights activist who sort of a protege of polymores and had been active in the labor rights movement. And as she’s delivering her like sort of farewell to now speech. She announces with no prior warning to anybody else that five months from that day in August of 1970, now was gonna throw a nationwide women’s general strike. To which everybody in the audience goes, are you fucking kidding me? And like all these women who now suddenly have to organize a massive action

Jeet Heer:

Yeah.

Moira Donegan:

and don’t feel equipped to do it and don’t feel like they have enough time and don’t feel, Betty’s saying this like into a news camera.

Jeet Heer:

That’s it, that’s it, I had it.

Moira Donegan:

And it’s sort of this trick that commits now to something very ambitious. And, you know, to these women’s great credit, they really pull it off. It was an unexpected runaway success. Tens of thousands of women participate across the country and in other countries. People stop going to work. They walk out of their jobs. They stop taking care of their kids. They stop having sex and doing housework. They are in the streets demanding equality and it is a massive coalition, much bigger than… what Friedan imagined for now. There’s older women, there’s lesbians, there’s student groups, there’s black women radical groups, there’s like all this vast swath of the American cameo population coming in for this collective effort at gender equality and their own liberation. Sort of premise of now is one that I think has gone like really out of fashion, which is that all women share an interest in the same political project of feminism. That’s like actually a wildly ambitious, optimistic, difficult strategy. Um, that Frigan herself found it like difficult to really adhere to and believe in, right? Um, but when it was done well, it had this electrifying effect that changed the country. I

Jeet Heer:

Mm-hmm.

Moira Donegan:

think really. dramatically for the better. And it was a wonderful moment.

Jeet Heer:

Yeah, no, it’s a great moment and I will have a link to Maire’s article which people can read about all this and you can also read her other writings in The Guardian and listen to her podcast, In Bed With The Right. And yeah, so Maire Donegan is out there for everyone who wants it. So again, thank you. once again for being on the program.

Moira Donegan:

Thanks, Jeet. I had a blast.

Subscribe to The Nation to Support all of our podcasts

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation