How Sports Betting Is Fueling Gambling Addiction

On this episode of Tech Won’t Save Us, Alex Shephard on the rising problem plaguing sports fans.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

On this episode of Tech Won't Save Us, Paris Marx is joined by Alex Shephard, senior editor at The New Republic, to discuss the legalization of sports betting in the United States, the growing influence of gambling in professional sports, and its negative impact on the lives of sports fans.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

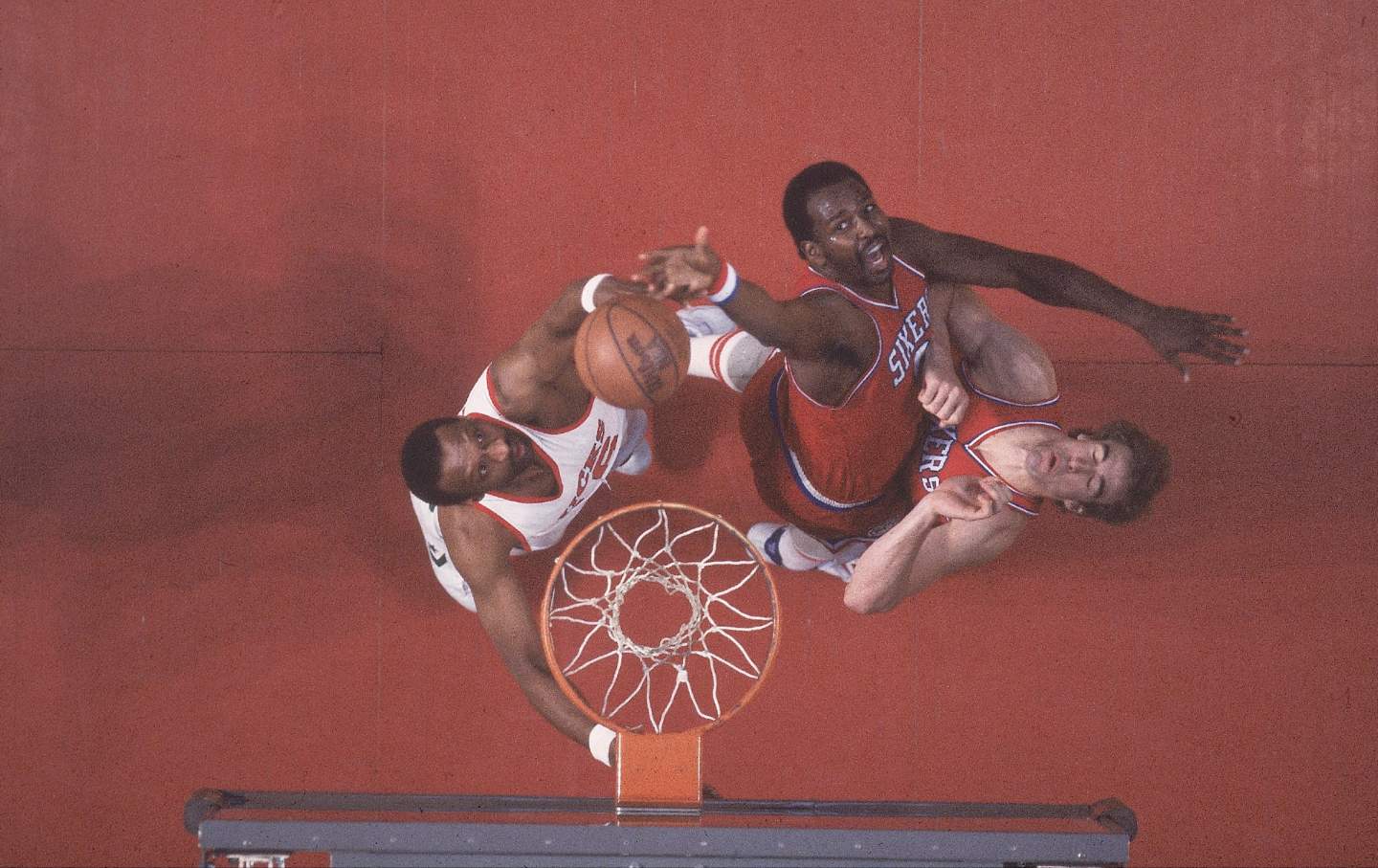

FanDuel.

(Pavlo Gonchar / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images)On this episode of Tech Won’t Save Us, we’re joined by Alex Shephard, senior editor at The New Republic, to discuss the legalization of sports betting in the United States, the growing influence of gambling in professional sports, and its negative impact on the lives of sports fans.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Paris Marx is joined by Ben Wray to discuss Europe’s capitulation to pressure from the United States on Nexperia, as well as on digital protections and labor rights that could have big implications for the future of work.

Ben Wray is a researcher specializing in the platform economy. He writes the Gig Economy Project newsletter and his most recent report for the ETUC is called Uberisation.

Our Sponsors:

* Check out Avocado Green Mattress: https://avocadogreenmattress.com

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Paris Marx: Alex, welcome to Tech Won’t Save Us.

Alex Shephard: It’s good to be here.

Paris Marx: Great to speak with you. You have this new piece in The New Republic, digging into this increasingly large problem of sports gambling. And of course, anyone who watches sports regularly, or even occasionally, will have seen how much these apps like DraftKings and FanDuel have become prevalent throughout the sports. Even if you’re not someone who regularly watches sports, you might just see it advertised on other shows or on podcasts that you listen to, because these ways of betting on these games have become so common. So I wanted to start with where this really came from. Because I feel like 10 years ago we didn’t see so much of this. So why has it become so common recently?

Alex Shephard: So basically, there was a law that was passed in 1992, that essentially banned states from creating their own laws regulating sports gambling, and it effectively banned all forms of sports betting in the country. There are certain casinos that may have had it, but for the most part, if you wanted to bet on sports, you had to go to a bookie or use an offshore account somewhere. Basically, what happened was that in 2018, New Jersey had been suing to try to legalize sports betting, effectively. And in 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that the law that had banned sports betting was unconstitutional. The way that we’ve seen the conservative Supreme Court do again, and again, and just kick issues that have been regulated by the federal government, in some way, back to the States. Since then, there’s just been a total explosion.

New Jersey was first because they had sued. They were basically ready to rock as soon as this law was passed. Here in New York, I could take the train to the Meadowlands and did a couple times, to place bets as early as 2019. But basically, by the end of the pandemic, or the “end of pandemic,” there were laws that had passed to legalize betting in dozens of states. Right now it’s at 38 plus Washington, DC. So, in theory, what you had was a situation in which it was a classic states’ rights issue, and classic dry constitutional problem. But states wanted to legalize sports betting, because it’s a revenue generator, that you can tax the hell out of it, and you can make a ton of money. So, when this ruling came down, the estimates were that it could open up something like $150 billion, nationally. You basically seeing a in steady increase, up to close to that number now, just in the intervening five years.

For the most part, there are some restrictions, depending on the state. But for the most part, if you want to gamble on sports,, I think the thing that the Supreme Court probably didn’t consider at the time was that you didn’t need to go to a casino anymore. That you could just do everything, on your phone. I think that that’s been actually the shift. I don’t even think that — and when I was reading through some of the coverage — at the time that people didn’t quite anticipate happening. That what you’ve seen is an explosion, yes, at sports books. And you can even go to some arenas, where there is an actual sports book in the lobby somewhere. But for the most part, if you want to bet, if I want to bet on sports here in New York, I can load DraftKings on my phone, or FanDuel and then various casinos, MGM being the biggest one also have their own sports books as well.

But what you’ve seen is a really fast embrace of sports gambling, both by states, but also by what are essentially tech companies that have gamified sports betting even more than it already is. So the explosion of prop bets, in particular is a big one. Those are extraordinarily profitable for gambling companies, because they don’t hit very often. And if you’re doing individual profits, you’re almost always going to lose money, and you’re very rarely going to make a lot of money. That’s where the door got kicked open here, I guess. It is that all of a sudden in 2018, if I was watching, let’s say Liverpool vs Manchester United or the Knicks versus the Atlanta Hawks, I would just be watching the game, you know, I might be looking at Twitter or something.

But now I can watch it and say: I think that Mitchell Robinson is gonna get in more than 11 and a half rebounds in this game, and Josh Hart’s gonna hit X amount of three’s. And all of a sudden, you’re watching the game differently. For states, there was a push here, because essentially it’s free tax revenue. So you don’t have to think about difficult things. Here in New York, state and local taxes are a huge deal. So you can kick that to the curb, but for sports leagues, and this is another thing that was not anticipated. In 2018 when this happened, essentially, there was a sort of hockey stick curve in terms of revenue from TV deals, and part of that was based on the assumption of globalization. That you can open up new markets. So if you’re the NBA, you’re looking at China, China’s got a billion people, so you’re selling TV rights on the presumption that you’re gonna have this huge explosion of money coming in.

For cable companies for a long time, sports was the most important moat. That if you want to keep people locked in, like if I want to watch the Superbowl, I can’t go anywhere else for it. I have to have a TV and a connection somewhere. But what you’ve seen is with the rise of the Netflix model, there’s been a huge surge in cord-cutting, that has diminished the ability for sports leagues to sell their TV rights to other companies, and to create bidding wars. You had a situation, for instance, last year in which the Women’s World Cup, which is a huge event growing and popularity, in a lot of countries, they were struggling to sell TV rights to it. So for leagues that require constant influxes of money, sports gambling also provided a new revenue stream at the time that it was desperately needed. I think with those two things there’s been a confluence there. That states want the money, sports leagues want the money. So, what you’ve seen is just this huge exponential rise almost every year. With that, which we’ll talk about in a second, an explosion of social problems as well, that have not been thought through at all.

Paris Marx: That’s fascinating to hear and, unfortunately, not surprising, but also very disappointing. Especially when we started to get into the broader effects. There are a number of things I want to pick up on there. But you talk in particular — and I feel like DraftKings and FanDuel are the big ones, but you can of course, inform me if there are other key ones there — were these companies that were already ready to go in 2018, when the Supreme Court decision was decided in order to kick it back to the States. And so the states could start legalizing it in the way that they have, or are these companies that really saw the opportunity of 2018 and then launched after that? And does the fact that a lot of these bets are being placed through apps and through these tech companies, does that diminish the amount of revenue that states potentially receive from it or does it not really matter in that case?

Alex Shephard: This is where I’m not an expert, fully. But I believe that what happened is DraftKings is American and was founded essentially, in 2012. Again, with the assumption that sports betting was gonna come, gamified, appified, sports betting was gonna come. FanDuel was started in Europe, where sports betting has been endemic for a very long time, and particularly in the UK, or at least, that’s the area in which I have the most knowledge or expertise of it, and experience. And so FanDuel was started, I think in Scotland, and it quickly merged with Paddy Power, which is the big sports book in the UK. Again, the assumption was that this was going to come to the US at some point. Basically, what you saw was by the end of 2018, they were really ready. So, DraftKings and FanDuel started to really advertise heavily in the US, in 2015-2016. Slowly build up, with the getting ready, essentially, to take over the online sports betting here in the US.

In terms of the principle of it, it’s not that different from the way that you would bet on sports 40 years ago. There too you would have an oddsmaker, and they would usually have some form of expertise that they would use to screw you over in some way. But what you see now, which is the big shift, is just that it is so easy to do. They were essentially using the exact same tech that you see in social media and, even things like Candy Crush, or something to essentially be nudging you all the time. At the same time the advertising strategy is then really aggressive. There’s a long period in which you couldn’t watch sports, listen to sports media, engage in sports media, and not just be constantly bombarded with offers of free money, essentially. So you still get them now, it’s a little less but, it’s essentially like a match, like you give us $1,000, we’ll give you $1,000. Obviously, that money stays in your account, so you have to keep gambling from it. That’s more or less how it started.

I think there is another element as well, which, again, is something we should probably get into a little bit later, which is that obviously it’s not a particularly great time for the media industry. Sports media, in particular has really struggled for a long time, local newspapers, or even larger. Regional newspapers were a kind of hotbed of where you’d get information about the Knicks or whatever. There’s been a huge contraction in that type of coverage, and the advertising money has just been completely destroyed by Google and Facebook. So companies like The Athletic, which was founded in the mid-2010s and was purchased by The New York Times a few years ago. Partly as a way to get rid of their unionized sports section, which they successfully did last year, which is evil. When you look at that coverage, what you see, it’s all sports betting stuff, like all the time. Everything is sponsored by FanDuel. Shams Charania who’s the big scoop guy for The Athletic. He has a video show that is sponsored by FanDuel.

For a long time, I couldn’t listen to it, because The Athletic’s flagship soccer podcast, which was started by a bunch of guys who used to be at The Guardian, that was also sponsored by Paddy Power. When you listen to it, you’re just constantly being overwhelmed with offers to bet. But what you’ve really seen, and this has been over the last two years, is on TV and media in particular, it’s just people are talking about gambling all the time — all the time. It’s sponsored by everything and that has been one of the insidious, creep elements here. Where you’ve just seen this slow rise, this infection, essentially, of gambling in sports itself. So when you’re watching baseball, now you see win probability. Which is stupid, because the win probability is the score. If the Mets are up for nothing, and you say: Well, the Mets are winning, they’re probably going to win. But that too, is where you’re seeing this kind of shift. It merges with the rise in analytics in sports as well, but it’s a nudge.

Again, if I have ESPN on, which sometimes do while I’m working, you get the lines all the time. Heat versus the Hawks, over under 190 and a half points or something, it’d be more than that. 212 and a half, let’s say So, that, I think, has been one of the more interesting elements here. Is that, as we’ve come out of the zero interest rate era, is that the ads and podcasts have shifted. So it used to be that you have a company who say: We’re going to disrupt the underwear industry. Snd investors are like: Well, screw it, we have free money. So we will invest in the underwear company. That money is gone now. When I listened to Bill Simmons or whatever, I’m not hearing about disruptions to food service or disruptions to clothing or disruptions to analog radios. What I’m hearing is two things. One is a return to more ordinary advertisements, like listening to Simmons, he’s advertising Shell gas and cars or something. But the one exception here is sports gambling. That’s this one tech company is doing it, because they know that if they can get people on board, you’re kind of stuck there for a really long time.

Paris Marx: I wanted to ask you about how the introduction of sports betting changes the way that the game is presented, and I hadn’t even considered the aspect of the media industry itself has been in a lot of trouble, the advertising has been declining. So, you need these new revenue sources to bring it in, so the introduction of sports betting then provides this whole new revenue stream. Not just for the leagues, and not just for the state and local governments and people like that, who are taking advantage of it. But also the media who is presenting it to a lot of people who are watching online, or watching on TV, or even on streaming, and being presented to them that way. How does that change the way that fans relate to sports? And when you go to watch a game, whether it’s in the stadium, or whether it’s just you sitting and watching on your TV, how does it change the experience of the game and the enjoyment out of it? Is it more annoying? Because all the sports betting is there? Or does it feel like: Oh, I have this new opportunity to engage with it, because now there are all these new stats that are being presented to me and I can maybe make some money. What’s the shift there?

Alex Shephard: It’s profound, because you just hear about it all the time. I go to the Knicks with some frequency. I watch sports out a lot too, and you’re just overhearing people talking about betting all the time or profits that they’ve that they’ve made. One point I overlooked earlier, is the other aspect of it as well, which is that the league’s have been obsessed to with essentially another cliff, which is just that Gen Z or younger people have are much less inclined to watch full games. There have been all these crazy proposals, particularly in soccer for how to deal with it. The chairman of Real Madrid was talking about we need to make soccer more like Fortnite or something. Like what the hell does that mean? But particularly sports saw this as a way to take keep young men on board, and it’s worked at least some extent.

But yes, you’re constantly hearing about profits. People are constantly just talking about this. The thing that I have noticed which has affected my ability to enjoy this, is there’s a real brittleness, I guess that’s kind of crept in. People are just pissed off all the time. Prop bets are hard — they’re really difficult to do I mean. Just to explain, a prop bet is essentially a series of bets. So when you think about betting, you think about: Oh, I’m going bet on a team to win. I’ll put $10 on the New York Rangers to beat the Buffalo Sabres. And again, that actually tends to be a better bet for sports books tend to make less money on it. With prop bets, you can theoretically make more money, but they’re harder to hit. So, the company is really aggressively push prop bets, because that’s where most of their money comes from. That is, essentially, making a series of bets. So they all have to hit for you to win.

So, if I keep my Rangers and Sabres thing. Let’s say the Rangers have a one and a half or a two to one chance, to make it simpler, to win. I put down 20 bucks, then they win, you get whatever. But with a prop bet it will be a series of things. So it might be that the Rangers win, then some guy scores a goal, and some guy gets in a fight, or gets a foul or something. Then when you do that, like if all three of those things hit technically, the odds are better. You suddenly take a bet that was two to one, and it’s now 18 to one, so your $20 becomes $350, basically. But that never works. People are just talking about this all the time.

Then the other aspect of it as well as people are yelling at the players, you know what I mean? They want, to use the example of Alex Ovechkin, to score a goal or somebody to do something and like they’re furious when it doesn’t happen. Especially because of the amount of alcohol in particular that’s involved in sports watching. You see this extension and there’s been a real interesting rise right now and you see with social media, too. I think that the players themselves hate it because people are just yelling at them about their bets. They open Twitter or whatever, and people are yelling about their bets. Social media was already bad because it turns everyone into a heckler and a troll. But it’s become significantly worse, and again, because people are like: You cost me $200 or whatever.

Paris Marx: I was reading in The Wall Street Journal that the point guard for the Indiana Pacers, Tyrese Haliburton, said that he was talking to a sports psychologist because of the negativity on social media, because so many people were placing prop bets on him. And of course, then losing money and getting really angry. The head coach of the Cleveland Cavaliers said that he was getting texts from people, because again, they were losing money, and they were angry. Apparently, this is a big problem in college football and stuff like that as well. It’s a real shift the way that people engage with the game, because now you’re not just going to watch it, or are not sitting on your couch to watch it and enjoy it. But now it’s a way that you’re making money, or more often, I guess, losing money. Much more common than in the past, again, because you’re saying you could often bet anyway, but it would have been more difficult. The prop betting in particular is that something that is made more common and easier to do, because it’s all on apps instead of some other more traditional way of betting on the games?

Alex Shephard: It’s a couple of things. One is just that you could always place prop bets, I would go to Vegas and place prop bets and stuff before. Because they are fun, but the reason why they’re so common is, I think they’re kind of similar. One is it’s a lottery system. So it’s not as big of an accomplishment, you don’t get as much money if you just bet the money line, or you just bet on one team to win. It creates a sense that there’s extraordinary amount of money to be made somehow, or somewhere. But again, the big reason is just that they’re really hard to hit. Most of the time you lose, and you might lose by one rebound, or one steal or a foul or a couple of free throws. And, that I think makes people furious. But the reason why they’re being pushed is just because that’s where they make their money. If you’re just betting the line, particularly just the money line or something, you’re not going to make a ton of money.

You have a 30% chance of winning, I think that number is down to 10 or lower with prop betting. When you multiply this by several million bets, or whatever you want to call it several tens of billions of dollars — it’s a ton of money. So the sports books themselves really, really, really push profits. That was the thing as well, there are a lot of sports podcasts I listened to for a while and they would do a prop bet at the end. They’d be sponsored by a casino or something, but that would be part of it as well. To go back to the earlier conversation, sports always make people mad — I get mad about sports all the time. I’m sure I’ve cracked a phone from the Buffalo Bills losing in the playoffs, even though I knew they’re going to lose. But what you’ve seen, and this gets to part the other problem as well, at least theoretically, they also exist as a way to form some kind of social bond with other people.

You’re sharing the same experience snd that experience is like: I want the next one. I want Liverpool Football Club to win. Prop bets erode that sense of solidarity — that sense of communal enjoyment because you have this kind of individual financial relationship with the game. Whereas before, I am from Elmira, New York, so the Bills, the Knicks. I’m Irish and depressed, so I like Liverpool. And in this instance, what you’re seeing is the degradation of that and I think that that’s one of the things that really hits me. It kind of creates this atomization of sports fandom itself, where all of a sudden, you’re not just invested in the Knicks winning the Knicks have to win and Josh Hart has to hit more than three and a half three pointers and get two steals. That sucks, it’s stupid.

Again, it creates the other issue as well, which is, I think one reason that I like sports, too, is I look at this thing all the time. It is one of the few things that I can just engage with, on a kind of psychic level, every now and then I’ll tweet something stupid during it. But for the most part, I want to watch it; I want to hang out with my friends, I want to experience a kind of social bond, and you see that cracking, with the rise of betting. Again, also with the larger infection of sports gambling here too where it’s like, you’re never just experiencing the game anymore. You’re also being reminded of: What’s the line? You know what I mean? And how can you make money on it? Or are the Mets going get more than six and a half runs? And that sucks.

Paris Marx: It absolutely does. Even as someone who is not someone who really watches sports, but to hear you describe it, I’d be super disappointed if there was something that I really loved and I was seeing this change happen to it. Where this communal aspect, this aspect of enjoying it with other people, was being eroded. Because people want to make more money off of it, basically. I feel like hearing what you’re saying, too. It sounds like the prop bets also take advantage of people’s love of the game and people’s feeling of the expertise. Because they’re watching it so much, they’re paying attention to the players. They’re like: Oh, I know, this person can do this. So I’m going to put some money on it. Then it doesn’t happen and they feel like that person has betrayed them personally or something.

Alex Shephard: There’s another thing too, which is part of it as well. There’s a FOMO element as well. Or, there’s an infection of hustle culture. That’s like: You should be making money while you’re watching this game. And if you’re not betting, you’re not doing it right. That’s the way that it gets pushed on you all the time. Ooe of the things that really makes me recoil is that I think it exploits the — whatever you want to call it — crisis in masculinity or something and people’s economic precariousness as well. Where it’s giving you a sense that this is thing that, again — was you think about the way that these teams started, for the most part — there are sources of local and regional identity and pride. And that’s not really true in the era of mass culture anymore, but it still exists to some extent. There’s been a real erosion in that, too. The games themselves, are seen as just another way for you to make money, to rise and grind, and you’re getting ripped off, and you do it too.

Paris Marx: I wanted to pivot away from talking about the fans and their experience in this to talk about the players. Because I feel like one of the things I picked up from the piece that you wrote was that there’s a growing number of scandals around the players engagement with sports betting and what it’s doing to that side of things. I was reading in the Wall Street Journal that the NFL had to suspend 10 players for betting last year and the NBA has had a growing number of complaints from players and head coaches about the influence of betting. It seems in particular, this scandal around Los Angeles Dodgers Shohei Ohtani, has really blown up recently. Can you tell us what that has been all about and what it says about the influence of betting when it comes to the players as well?

Alex Shephard: You see it kind of everywhere. The Otani scandal is a goofy one. So he’s a Japanese player; he doesn’t speak English. He just signed this massive, I think, $700 million contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers. He’s an amazing player. He’s the best player in baseball. He is this baseball savior. He pitches; he hits. He does both things extraordinarily well. But he’s also this weird cipher — no one knows anything about him. People didn’t know what his dog’s name was, for a long time. It was revealed when he started the Dodgers, he got married, and he was just like: Hey, I’m married now. And everyone just like: Ooh, to who? And found out 48 hours later. Part of that just a private guy, but also, essentially everything that he did was mediated through this translator, who was also his best friend.

Basically, what happened very quickly, it was a weekday evening. The Dodgers fired the translator and nobody knew why and then quickly, there’s it became clear that Otani’s account had sent four and a half million dollars to a guy who was running an illegal sports booking in Anaheim or somewhere in Southern California. So, the question was immediately: Well is Otani betting on baseball? There’s famously the Pete Rose scandal in the 1970s, 1980s, that ultimately led to Pete Rose — who had the most hits of any player ever — being banned from baseball and from entering The Hall of Fame. Going back even further, there was a scandal in 1919, which resulted in eight players who were banned forever for throwing the World Series because of the mafia involvement. It’s a good John Sayles movie, “Eight Men Out,” that’s about that.

So, there was this concern. It does seem like what happened was actually that the translator was a gambling addict and did steal this money from Otani. He’s facing federal charges now for doing that. But that raised the salience of this issue there. In basketball, you had another situation where this guy Jontay Porter, who plays for the Toronto Raptors, he’s the scrub, the end of the bench player. But it seems like what was happening was that he was in this Discord chat, or WhatsApp group, but I think Discord chat with a bunch of guys. They would say: Look, play a little bit and then call out sick, and they would place these prop bets on him getting less than four rebounds, less than one three pointer. And this was flagged by FanDuel, maybe DraftKings, maybe both because they were like: Oh, we’re seeing the biggest payout that they did for these two games that he allegedly did this, were on prop bets made on this guy who plays six minutes a game for the Raptors and who stinks.

His brother’s a freak too. But that’s a whole other subject, but his brother is good. And you’ve also seen this in European soccer. So Europe is interesting, because they’ve had legal sports betting for much longer. and you can really see this. If you go to a place like Blackpool and England, or something, you see societal rot, in which sports gambling has played a major role. I’ve been wandering around there, and you just see dead-eyed people. But there’s a player Ivan Toney, who plays for Brentford, who was suspended for most of, I think, eight months, because when he was in the lower league, he had placed hundreds of bets. There’s a big scandal in Italy, essentially, in which three of their best young players who had all played together, also had placed hundreds of bets.

One of them plays at Juventus, had lost over a million dollars, [Sandro] Tonali has been banned, I think for over a year. He’s going to miss the European Championships this summer. It was found out recently, or it was alleged recently, that he had continued to bet on sports even after he had been suspended. So, there are a couple of things here. I think there’s a needle to thread and when you talk to people who are defensive of the gambling industry, what they will say, for the most part is like: Oh, well, these companies flag these bets. You saw that with Jontay Porter and the Tonali bets, they were made via illegal, like apps. And they say: Well, those are illegal bets. The players aren’t supposed to bet on themselves anyways. But I think you’re seeing two things. One is a question about the integrity of sports themselves. It’s probably likely that Jontay Porter will get a lifetime ban just to be made an example of.

Tonali, again, is going to miss out on two years of what is essentially his prime or close to it. He’s young, but he’s a very, very good midfielder. And it’s because sports are trying to protect the integrity of the game. But I think what people overlook here is that the target demographic for sports gambling is essentially men in their 20s. Athletes are men in their 20s, for the most part. They are gonna get caught up in the same types of societal rot that other people are. Sandro Tonali is probably a gambling addict. Ivan Toney probably has a gambling problem. To move it into an even bigger picture that I think it’s interesting about Ivan Tony is a he plays for Brentford, FC. Brentford is owned by a professional gambler; they are sponsored by a gambling company.

You create this weird world in which the players rightfully are banned from betting because it screws up the question of: Is this real. Are the players trying to win? But everywhere they look, like Ivan Toney, when he came back from being suspended for gambling would look down on his shirt, and it says: Hollywoodbets. You’re being just reminded all the time — just bombarded. That the sides of the stadium are Paddy Power ads. But usually, that’s certainly the case in some parts of Europe, too, or William Hale, or whatever they have there. I think that that’s the larger hypocrisy question here. Obviously, the integrity problem is a big one and it’s one that the leagues are trying to solve by dishing out pretty severe punishments to players to try to make examples of them. But gambling is an addiction.

So, with the exception of the Porter scandal, which is pretty minor, there hasn’t been anything major that I’ve seen that suggests that there’s been anything that’s really screwed up, in the way that the 1919 World Series was literally thrown by the mafia. But you see it in all these other little ways. Again, it’s being done just for stupid reasons. So people make money or even just that they feel like they have a sense of control, and I don’t really know what they can do about it. I mean, I think to some extent, there’s going to be a huge rise of enforcement and I’m sure that the teams are going to be monitoring what their players are doing as well, to an extent. But at the end of the day, these are guys in their 20s, and guys in their 20s gamble. They gamble, because everywhere they look, they’re told to gamble. It’s become a societal norm — they want to be a part of this thing.

I have people in my family that have gambling problems, or have had gambling problems. And again, how you control that is an nteresting question. But I think there, what we’re seeing, and I don’t know how it stops, essentially. It’s you’re seeing a slow increase in still relatively minor scales. I mean, Ivan Toney and Sandros Tonali may have bet hundreds of times, but Toney never bet on a game he was playing in. Tonali, there have been some allegations that he may have picked up a stupid yellow card here and there for gambling reasons. But it’s not something that affects the outcome. But what you’re seeing is you introduce poison into the ecosystem, into the water, everyone drinks the water. And that’s going to include players who are involved in this too.

Paris Marx: So I guess the bigger issue or the bigger concern is less than using insider knowledge from the sport to make their own bets, but rather starting to change how they play, because they have relationships with people who can place bets and are gonna make money off of that because of it, I guess.

Alex Shephard: That’s probably the larger concern at this point. They do have very protected inside information. It’s proprietary. It’s a guy who got arrested for stealing information — this is not gambling related — but worked for the Timberwolves. Then you see things leak out with lineups, and other things like that, that can affect gambling. I like to play a fantasy Premier League or something and I was getting mad, because some guys know who’s playing and who’s not beforehand. I don’t know that, and that doesn’t matter, because it’s free and doesn’t really affect anything. It’s 100% possible that you will see some major event that is skewed in favor of gambling interests at some point. But what you’re more likely to see is just thousands cuts scenario in which every now and then Jontay Porters of the world are probably more concerning. Because they might just want to be cool, they might want to feel like they’re participating in something. But also Jontay Porter is on a couple of 10 day contracts for the Raptors, his brother’s got $100 million, or whatever. But he’s making more than me, but not a lot. I think that it’s an opportunity for them to cash out too and that shouldn’t be overlooked either.

Paris Marx: That makes a lot of sense. When you were talking about the broader impacts, and what the players were doing and how they’re still in their 20s, as well. And they have the same pressures and wants to do this gambling like anyone else, I think that gets us into the bigger question that your piece was really getting to. When you call the sports betting, sports gambling, to be very clear about what it was. And the broader impacts of having these gambling ads everywhere, every time you see sports you see these encouragement to place a bet or place a bunch of bets, when we’re talking about prop bets, on different things that are happening in the sport. How that pushes this greater prevalence of gambling within society and, of course, this addiction to gambling because then you lose some money, and then you want to try to make it back. You’re constantly making more and more bets. So talk to us a bit about that aspect of this, how, by legalizing sports betting, you now have a lot more people who are engaging in this gambling, getting addicted to it, and the crisis that that causes in their lives.

Alex Shephard: The extent to which is normalized, as well. I think like binge drinking is a reasonable comp here too in that you look at the way that Budweiser is marketed or something. It’s like you hang out with your friends, you drink a bunch of beer or whatever. Don’t you want to hang out your friends and drink a bunch of beer? Gambling has a similarly insidious, soft marketing side to it. It’s just like: Don’t you just want to hang out at the bar with your boys and bet on college football or whatever? And what you’ve seen really quickly is just a huge explosion in addiction. Which is not surprising at all, because it’s so easy. It used to be, you would still have to do something. Like you would have to get money, you would have to call somebody, you’d have to give the money to somebody else. Usually you’d have to get in your car.

Paris Marx: There was some friction in the process of placing the bet.

Alex Shephard: Exactly. And I think now you have a situation which there is no friction at all and that’s a huge problem. So it’s still pretty early, but there are states particular in the Northeast that have been really good at studying this. New Jersey was the first state to legalize sports betting and they’ve essentially seen a steady climb in calls to gambling addiction hotlines over the last five years. In Connecticut, they legalized gambling in 2021. They saw a 91% increase in calls of gambling addiction hotlines. There was a paper that came out that I thought was really interesting, late last month, I think on April 1 actually. From the University of New Mexico that essentially found extremely high rates of correlation between binge drinking and sports gambling, which is not surprising.

But again, too, it’s one of the things that’s overlooked here is that’s also the way that it’s kind of sold as well. That this is the thing you go out and you do, you go to the bar, and you place bets. And again you’re just seeing, you look at the credit crunch right now — that’s an inflation problem more than anything else. But I think that it’s also true that people are looking for magic ways to get more money and sports gambling really, really aggressively markets itself as a way out. I was having conversation with somebody over the weekend. The way it works is you lose money, and then you’re like: Well, the way I can get this money back is easy, I’ll just placed another bet. You just get trapped in that cycle really quickly. And the bets hit sometimes; some of the bets work.

Paris Marx: You need to occasionally win to keep coming back.

Alex Shephard: But overall you lose. I think that the way it works with your brain is is a similar thing that it gives you a sense of control over these these kinds of events. And you feel like: Okay, if something bad happens, I can make something good happen just by picking up my phone and clicking a couple buttons. And it’s that type of, sort of, vicious cycle that is ensnaring a lot of people A.gain the companies are just extremely aggressive in the way that they onboard people. I think there’s going to be a point. I don’t think it’s a situation in which there will be exponential growth forever in terms of sports gambling, but there’s a huge amount of market capture here. The apps themselves claim that they’re good at flagging problems better, but at the point that you’re flagging a problem better too it’s maybe too late for somebody, as well. Again, some of them accept credit cards, which is insane to me. It’s just a completely screwed up system in which you can ruin your life with a couple of stupid bets.

Paris Marx: I’ve read as well, you were talking earlier about how a lot of these apps, I don’t know if they still do it, but would basically say: You can have free money to start getting into it. Then once you do sign up for the app, once you’re into it, especially when you’re watching one of the games, you’re constantly getting these notifications to place additional bets on things that are happening as you’re watching. So like we know with Facebook, and the social media platforms, and the way that many of these apps have been designed over a long period of time to use these push notifications, to get you to come back and even learn from gambling techniques in order to design their systems. It’s no surprise then to see gambling apps that are designed to get you to bet on these games and I’m sure things beyond that as well. To use the same tactics, to get you to come back, to get you engaged in the system. To make sure that they’re keeping you engaged and spending money, essentially.

Alex Shephard: I like sports radio, too. But it plays on a kind of similar impulse which is that people want to feel like they understand. Like they have some sort of mastery over these systems and the games themselves. I think that that’s the other way that profts work too, is that it’s a la carte. You’re not just doing the same thing that everybody else is, so when one works, it’s because you’re you have special knowledge. I don’t know why I keep using Josh Hart as an example. But whatever, New York Knicks swing man, Josh Hart, and I think that that part of it as well, is that what it’s selling to you is the sense that you understand what’s happening right now. And you don’t. Like the casinos know like, they’re really good.

The handful of times I’ve done prop bets on DraftKings or FanDuel, you’re just like: Oh, yeah, they’re usually not far off. Like when they say four and a half rebounds, they mean four and a half rebounds. You’re probably going to miss a prop that by one or two. And that I think is the other element of this is that you may hit two of the three in a prop bet, but you’re going to miss by just a hair and that near miss feeling is actually the thing that makes you kind of hooked. Because you’re like: I was this close, but I can get it next time because I got it right. I figured out the point is this rebounds, but you’re always going to be this close because they have large computers that are running huge numbers of simulations to figure these things out, I assume.

But however they’re doing it they’re usually very good, you’re not going to beat the casino — that’s the whole thing. Only Donald Trump can lose money running a casino and I think that’s a big part of it. Again, it’s almost impossible to watch anything without there being some reminder. The American soccer coverage is a little bit less than most ,but even there it’ll just be like: The odds for Liverpool Arsenal-Manchester City to win the title right now. And you’re just kind of like: They’re all one point away from each other! Of course the bookies think Manchester City’s going to win because they won it for the last five years. So it doesn’t really tell you anything, that’s the thing it makes me crazy about it is. I’m just like: I’m not learning anything useful here when I’m being told this just: What if you bet on this right now. Liverpool’s plus 450.

Paris Marx: Definitely. When you think about the broader impacts of it, as you were describing, with so many more people calling into these gambling hotlines, and the fact that the economy itself is not in the greatest place right now. A lot of people are struggling in the sense that because we’re in this inflation crisis, because the cost of everything has gone up so much, because people’s mortgages have gone up so much. There is this general stress that companies like this can take advantage of, in saying: Hey, you need a bit more money, try placing one of these bets.Then, of course, naturally, when they lose many of those bets and lose a lot of money, you end up in this spiral. In your piece, you talk about the connection between gambling addiction, and substance abuse and alcohol abuse and binge drinking and things like that. It’s completely understandable how that happens. Because you can already be in this desperate situation, then you’re even more strapped for cash, because these bets have failed. Then of course, you start drinking more, because I’m in this terrible place.

Alex Shephard: I mean there’s another possibility too, which is just that if you’re predisposed to high risk behavior than being introduced to another easy way to do high risk behavior. And if you’re engaged in something that for instance, decreases your sense of inhibition, or your ability to manage risk, or even your ability to really look at things in a longer term, which is essentially is the appeal of alcoholism, to some extent, to the extent that t it has an appeal. It’s sort of all of the above. But again, the larger situation is, I go back and forth on it. In some ways, alcohol is a really good, a really good example, in that most people can just have a glass of wine, or whatever, or two glasses of wine. Sometimes three glasses of wine, and they’re fine. But there are other people that if you have one glass of wine, then you’re going to have 15 glasses of wine — that would be horrible for the sugar intake, but whatever. I think that the problem here, for me, is also just the phone element. There too, you at least still have to go out and buy a bunch of wine or a bunch of beer, whatever you want. And here, it’s just so easy to get hooked on it and to be just trapped there once you get there, That I think it’s really, really dangerous and there’s just nothing to be done.

Paris Marx: On that point, obviously, we’re talking about how a lot of state governments, governments legalized this over the past number of years after the Supreme Court decision, because they saw the opportunity of the revenue that came with it. I’m sure they were being lobbied by the companies that want it to be legalized so they can make their money on sports betting. Have we seen as these potential impacts have been growing, as you were talking about, as state’s have seen calls to these gambling addiction hotlines increased significantly since the legalization of sports betting. Has there been any move to try to rein this in? Or at least place some rules around how it works?

Alex Shephard: No, not at all. You’re not really seeing anything like that, anywhere. I was doing a cursory search earlier. No, I mean, I think the problem with it is, in the same sense we’ve been talking about this vicious cycle that leads to gambling addiction. It may sound crass, but there’s a virtuous cycle that is led to the spread of this, or virtuous if you are making money off of it. Which is that obviously, betting interests law have spent a ton of money to make sure that they can legalize gambling everywhere, because they make a lot of money and states are strapped for money, and you can tax this heavily. Maybe you don’t have to pass a, tax levy or something because you’re getting more revenue from gambling. And that was why New Jersey wanted to do it and sports leagues are looking at an very, very uncertain future. I think that that’s something that’s been under cover recently.

But they had been pitching themselves to owners as essentially a font of unlimited growth. They’re gonna take over the world, and there’s gonna be cable revenue and everything else. They are seeing that dry up, so they’re looking at other places too. Gambling provides a window there. And again, as I was saying before, they’re also extremely anxious about the TikTok generation or whatever and this is a way that you can literally capture people into watching sports. And then of course media too, which is similarly in pretty deep trouble because it’s media and everything else. It’s very quickly reorienting itself and pushing gambling stuff. You see, they’re just huge, if you go to The Athletic, that’s a great example. It’s just gambling stuff all over it. Advertisements are gambling, they’re tips about gambling.

Again, part of that is that’s what your readers want, and you’re providing it to them. But for all of those entities all of which need money, or at least want money very much, but this has been a real boon. It’s relatively under covered still, and if you look at things in places like Europe, and England, in particular, there’s a lot of really good writing and has been. Particularly in The Guardian, which has been very good about sports gambling. That drills in on the societal impact that the Premier League’w embrace of gambling has had on British society. Which was mess before anyways, but they haven’t done anything there either. And I think here as well, it’s sort of being treated like any other addiction problem, which is that it just gets swept under the rug.

It’s like alcoholism or something as well, you’re not gonna see prohibition. It’s crazy that that was ever a constitutional amendment, but that era is long gone. Again, I think that for the states, it’s free money. They’re not thinking about it in terms of the larger societal cost as well. There is an actual cost to both the societal fabric, but also an economic cost, too. And that’s not being considered here, either. But, again, it can be a problem. But Joe Biden wants young men to vote for him. Donald Trump wants young men to vote for him, they’re not going to be like: Sports gambling is terrible. It’s not a winning political issue in that way.

People like sports gambling, they’re not concerned about the other problems, in part because that’s a part of a larger discussion we’re having. It’s an atomization issue. Gambling addiction is something that happens to other people. But the ultimate result here, for me is a situation in which everything is being degraded. The sports are being degraded, the societal fabric is being degraded. You’re constantly being told to do things that cost money, that are outside of the actual enjoyment that you get from something. You’re getting further and further away from the sense of connection and joy and pain and whatever you feel from watching sports. It’s being replaced by a synthetic version of that, that I think is really gross.

Paris Marx: I think that’s an essential point that, obviously we’re seeing far beyond sports, and in many other parts of society. The only thing I was trying to look up any initiatives to try to rein this in and the only thing that I saw was the college sport league, NCAA, trying to push to stop player specific bets in and a few states have done that. But but that’s about it. Alex, this has been a sobering not particularly positive conversation. It hasn’t told us the world is getting better anything, but I think it is good to understand the impact of this, what it’s actually doing. I really appreciate you taking the time to come on the show. Thanks so much.

Alex Shephard: It was great to talk to you, take care.

Subscribe to The Nation to Support all of our podcasts

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation